Some biblical scholars have attempted to identify “Lud-im” with the “Lyd-ians”, but there are problems with this identification.1 Primarily is the fact that Lydians didn’t settle in “Mizraim”, nor anywhere along the Nile river. Their kingdom was much further north in Anatolia, bordering the Greek Kingdoms, and their traditions and mythologies often bleed into Greek. Therefore there is no reason to think Lydians are not brothers to the Greeks, in other words Indo-Europeans, and the Greeks never felt the Lydians were so far from them ethnically.

Putting a final nail in the coffin for this theory is the reality that there is a Hebrew term already for Lydians, which was סְפָרַד “Sfarad”. This term for the Lydians comes from their endonym “Sfard”. Sharp readers will notice this term is actually the same as “Sephardi”, the appellations for the region of Spain. Oftentimes we see exilic Jews apply terms they have for other regions, or peoples, to the lands they are settling. A perfect example of this is the term “Tzarfat” which was originally a city in Lebanon called “Sarepta”, it was eventually applied to “France” owing to the fact a reverse spelling sounds out “F-r-ts”.2 Ashkenaz being called “Germany” is another earlier example of this effect. In this same way “Lydia” or “Sardis” was later applied to “Spain” potentially owing again to similar sounds. This is often why scholars would become confused over similar terms in other periods, because usage of a term for a region doesn’t necessarily imply that “term” was native.

Looking at biblical references we can see a few potential confusing terms. Shem also has a son “Lod” which is likely the origin for the Israelite city of “Lydda”, but we will further analyze options for Lod in a later discussion. We can thus exclude these references to Lod quite easily.

Mishnah Gittim I has a helpful reference to both “Ludim” and “Lod” listing them directly next to each other in the context of villages, calling them the “village of Ludim” implying a non-centralized tribal power. Now the traditional interpretation of this line is that “Lod” refers to a village inside Israel, clearly the previously mentioned “Lydda” and that “Ludim” is a reference to villages “outside of Israel”, but still not far off and possibly just beyond the border. In a sense these terms are being used as an analogy for “from outside to inside” or “from unknown to the known.” We can see here a rabbinic usage of “Ludim” to refer to unknown, mysterious lands, offering a potential clue for the term. It is possible that like Sfard, Tzarfat, and Ashkenaz, the term “Ludim” was later applied as an appellation for the furthest lands from Israel, and the known world.

Helping support this theory might be a reference in the Talmud3 where it uses the appellation “Ludim” exclusively, without any of his brothers, and without being in any Egyptian context. In the Talmud it uses Ludim as a replacement for “cannibals”, but more importantly this term is listed in a series of six eating periods, progressively getting closer to a “more holy” time to eat. The first period is the eating period for the Ludim, in the first hour of the day, compared to the Sages who eat in the sixth hour of the day (conveniently one hour before the “7th hour” which represents Shabbat). This supports the fact that “Ludim” were used for a sort of savage people of far off lands, essentially ‘uncivilized’. This would be referring to the people “in the farther reaches of the world” - similar to the context of a troglodyte - and might explain some later usages of the term.

Checking into other rabbinic evidence we have Saadia Gaon’s explicit designation that “Ludim” are identified with Tanisiin, the Hebrew term for Tunis, capital and center of Tunisia. This may support our theory that it was being used to refer to the “far west”, somewhere in Africa. In ancient periods this region was certainly Hamitic owing to Carthage’s Phoenecian origins in Sidon. Saadia Gaon was from Baghdad and the term “Tanisiin” from him is contextually meant to apply to “North Africa” rather than Tunis proper, generalizing the area which these Ludim inhabited.

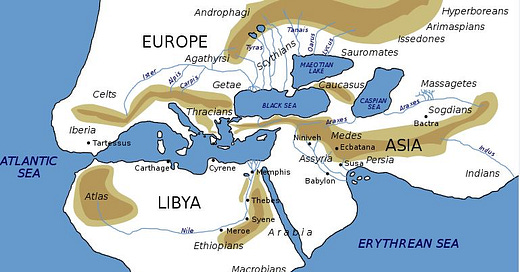

Pliny seemingly agrees with Saadia Gaon naming the river “Laud” in Morocco near the modern site of Oued Laou.4 This does line up with the North African coast which in this era had yet to be settled by Phoenecians. Furthermore the river was reportedly navigable in this period. However, it is unlikely the specific location of the Ludim, but does provide regional clues, even if they may have moved to these places in later periods. Where did the Ludim originally come from, if they inhabited North Africa later? The Ludim were a people who came from Mizraim, and what is far more likely is that sometime within the nearly one thousand year period the original Ludim had moved, or settled at some point around North Africa. Sparse records from periods before Berber arrival makes it difficult to know who was inhabiting this region prior to their arrival.

Now previously we brought up the actual boundaries of the Nile snaking around the African continent according to most, if not all, ancient writers. The origin of the Nile was supposedly located in the Atlas mountains, lining up nearly with a “generalized North Africa” since the Atlas mountains stretch across the entire north from Morocco to Tunisia, not far from Tunis. Most of the northern area aside from the coast would be considered “The Atlas Range” in classic times, making the difference between Laud and Tunis negligible.

If we are to go off this theory that “the Nile started in the Atlas”, is it farfetched to conclude that the “first son of Mizraim” would also dwell somewhere near the headwaters of the Nile? In my eyes this seems likely, but it would be unclear who specifically the Ludim would be since we are unaware of the people located around the Atlas in this period. It’s very possible these were mostly nomadic people - as many of the Saharan populations were - who eventually found their way to Egypt by the New Kingdom.

One supporting theory for this is the reality that the Ludim could have moved to Egypt as a sort of mercenary class which is implied through most of the references to Ludim. Many of these references call the Ludim those who “grasp and draw the bow” such as in Jeremiah.5 Oftentimes mentioned alongside Phut, who we will see later are also frequent mercenaries hired by the Egyptians, the implication is that Ludim were often employed by the Pharaohs. What is interesting in this specific reference is Jeremiah’s period during the reign of Pharaoh Necho II. According to Horodotus, Necho specifically sent out an expedition of Phoenicians who sailed from the red sea, all the way around Africa, reaching Gibraltar not far from Laud, and returning back to Egypt. While this tall tale seems unlikely, it attests to Egypts awareness, and connection, to the lands further west in North Africa making it very possible for a group to have moved from there to Egypt.

There is a difficulty with this “bow” association, owing to the Pesedjet - translated as “Nine-Bows” - an Egyptian generic term for “foreigners”. This term was variously applied to anyone acting as enemies of Egypt, and oftentimes foreign mercenaries would start off as enemies before being hired for their military prowess. As the enemies of Egypt changed, so too did the list, making no single “group” a proper identification for the Nine Bows.6

It’s possible that the Torah is using the same language of the Egyptians when it calls them “people who draw the bow” and alluding to the fact these were foreigners, and mercenaries who had settled and mixed into Egypt proper. Metaphoric language in Egypt would often place the Nine Bows underneath the feet of Pharaoh to literally show their domination by the Pharaoh.7 It’s not that far off to assume “domination” eventually meant ethnic and cultural assimilation. We see the Torah employing Egyptian language relating to the Nine Bows in Psalm 110:1 where it says “...until I make your enemies your footstool” potentially alluding to this metaphoric language often employed. Helping support this shifting theory of bows is Djoser’s usage of the term where he utilized it in reference to the Nubians, showing how anyone outside of Lower and Upper Egypt attacking would be referred to with this generic moniker for “enemy”.

So far the most likely location for the “Ludim” are somewhere in North Africa, whether the coast, or generalized Atlas range. Their associations with Phut - who we will see lived in “Libya” which was a much larger region in this era - help geolocate these people close to the Phutians. Potentially supporting this theory is the traditional identification of the Ludim by Rashi where he says they were called Ludim due to having “fiery faces”. I propose this later identification by Rashi was a result of these people having been called “burnt” visually and skin tonally. Oftentimes Greeks referred to anyone from Africa as having a “burnt face” implying a darker skin tone likely owing to their African origin. This term clearly got lifted into Hebrew.

Hippolytus of Rome, but also modern scholars such as Victor P. Hamilton (31 October 1990). The Book of Genesis, Chapters 1-17. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 264–

Kahn, S.; Broydé, Isaac; Gottheil, Richard (1901–1906). "Ẓarfati, Ẓarefati ("French")". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

Shabbat 10a

Pliny, Natural History, book 5

Jeremiah 46:9

Tait, John (2003). 'Never Had the Like Occurred': Egypt's view of its past. Great Britain: UCL Press. pp. 155–185

Cornelius, Sakkie. "Ancient Egypt and the Other". Scriptura: 322–340.

Just a note:

Rashi there refers to the Lehabim as called that due to their fiery faces. The root of the Hebrew word for fiery is "lehav" so it's a direct linguistic connection. You may be correct in your interpretation on lehabim, but that's still not related to ludim.