Around the year 2750 BCE there was a marked advancement in regional technologies and an increase of centralized polities. During this period the rise of multiplex city-states led to what we could view as the progenitors of modern political nations. A war sometime around ~2700 BCE between Sumer, led actually by Enmebaragesi of Kish, and Elam is probably the first recorded war. The oldest (surviving) peace treaty in the world is between Lagash and Uruk around 2500 BCE, inscribed on a clay nail.1

Much of these effects can be seen in the Epic of Gilgamesh, which could have entire books devoted to its analysis. However, the most important historical text is not actually the famous epic, but rather a document called “Gilgamesh and Aga”, otherwise known as The Envoys of Aga.

This simple text describes a siege of the city Uruk by King of Kish, Aga, whereupon Gilgamesh refuses to submit to Aga’s authority leading to Aga’s defeat and the collapse of Kish.2 The theoretical dating of this war places it between Early Dynastic II and Early Dynastic III sometime around 2600 BCE, but early enough we could call this the start of the era from a Sumerian perspective.3 Some scholars view this story as a reflection of the early relationship between Semitic and Sumerian people groups.4

Realistically what this story attempts is a metamorphosis from the previous nearly immortal kingship of the Kishites into a more worldly reign with Gilgamesh being the first ruler - other than the likely inserted Dumuzid - to have under 300 years claimed for his reign. In effect, this narrative depicts the transition between the proto-nation states led by hero-kings to a more political form of ritualized power transfer.

One theory for why Kishite rulers lifespans from the first and second dynasty were so long could come from the same theory of insertion of Sumerian rulers onto the list. Just as Gilgamesh, Lugalbanda, and Enmerkar appear like additions form the later Sumerian Ur dynasty, the Kishite kings appear like insertions by the Semitic rulers of cities like Kish, but importantly from Akkad. Furthermore, later kings of the Ur dynasty would call Gilgamesh their “divine brother”, showing a process by which fathers, sons, and brothers were amalgamated into one family by later rulers.5 In effect we see the list almost like a dueling version of history, with attempts to usurp other cities' claims through complex propaganda.

Looking at an often overlooked clue is the actual name of Gilgamesh, which is a romanization of the Akkadian form rendered “𒄑𒂆𒈦Gilgameš”, which itself is derived from the earlier Sumerian “𒄑𒉋𒂵𒎌 Bilgames”. The name simply translates to something like ‘the kinsmen’, but alternatively probably refers to the progenitor of a house, rather a lineage, of kings. Some have suggested that the pronunciation of the name should be closer to “Pabilgames” to imply familiar relations, although this view is not widely supported.6

Eagle-eyed readers will already notice the similarity of this prefix ‘Pabil’ being nearly identical to ‘Babil’, or Babel/Babylon adding loads of confusion to the figure of Gilgamesh. Given this is not a completely supported reading of the name, it’s difficult to verify if there was any connection to the story of Babel, and the confusion that was begotten by the more than likely cyclical builders of Ziggurats which included Gilgamesh - himself an amalgamation of many Early Dynastic mythos.

Gilgamesh does have a son, and grandson who supposedly rule over Uruk, but it’s very unclear if these are again later additions from the Third Dynasty of Ur referring to themselves as “sons” of previous rulers. Gilgamesh was likely the collective memory of that period, with his successors being back-filled into the list by later historians and chroniclers. This is all very probable when looking at the list's complete exclusion of the Dynasty at Lagash, which we will shortly.

Following the kingship at Gilgamesh’s Uruk there is a continual shifting of said kingship around the region. It eventually returns to Kish where the rulers are again given mythologically long lifespans at a time when supposedly these spans were normalized in many other cities. Eventually we arrive at one of the less mythological figures on the list who reigns for only 60 years named Enshagkushana who goes by the title “lord of Sumer and king of all the land” implying his obvious unification and empire building.7 Very little is known about this ruler, but he appears somewhat historical.

After the reign of Enshagkushana at Uruk; between 2500-2271 BCE Lagash rose to become arguably the most important regional city in Sumeria. Inscriptions describe these kings having taken over Sumer, Kish, and the entirety of wider Mesopotamia even as far as Mari in the north and Elam. As mentioned, these rulers do not even enter into the Sumerian Kings List with a totally separate competing list “The Rulers of Lagash” appearing like a satirical parody of the more well known Sumerian listing. Lagash clearly viewed their list as a joke, even if elements included real history.

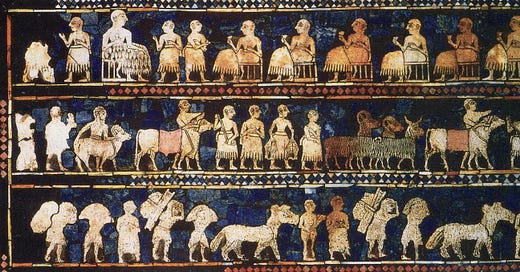

Lagash’s history begins with a supposed En-hegal who purchased land around 2570 BCE. He does not appear to be a king, and eventually is succeeded by the High Priest (Ensi) of Lagash named Lugal-Shaengur - Lugal simply meaning lord rather than truly a king - helping build and renovate the temple of Ningirsu. Next comes Ur-Nanshe around 2520 BCE who doesn’t appear familiarly related to the previous rulers making the real start of the ‘dynastic’ lineage of the Lagash kingship. Numerous inscriptions and texts verify Ur-Nanshe's existence with his widespread unification being obvious to any reader. We even have pictures of Ur-Nanshe, shown on the image to the right. Importantly he is the father of Akurgal, himself the father of the important Eannatum8 who is depicted on the Stele of the Vultures and expanded the empire to a ‘global’ size by defeating Umma9 - if Ur-Nanshe hadn’t already unified much of the territory.

On this same Stele comes the curious story of an over 150 year long war between Umma and Lagash.10 The impetus of the war appears to be a fertile tract of land with a deep canal dug by the King of Kish called “Gu-Edin”, or “Gu’edena”. This territory was actually the trigger for the war with both sides laying claim to the fertile plain which must have had a high agricultural output.11 The war isn’t really that important, but does serve as the backdrop through which kings had their power shaken in the region, appearing as a central location of conflict. However, the name of the plain does obviously call back to the Garden of Eden. While in this period, I would promote the Garden as long “lost”, this territory might have once been the location of Eden still providing very fertile territory for a civilization as prime agricultural real estate.

Next comes the confusingly named Enannatum I, brother of Eannatum whose rule actually sees the independence of Kish under Kug-Bau, and the independence of Umma. His reign around 2420 BCE is obviously marked with significant problems that his father and brother didn’t seem to face. After Enannatum I’s tumultuous rule, his son (again, confusingly) named Entemena defeats Umma and asserts Lagash’s unified rule.12 He actually accomplishes this task through an alliance with the ruler of Uruk, Lugal-kinishedudu, successor to the mentioned Enshakushanna who unlike any of these Lagash kings is listed on the Sumerian version.13

The final member of the dynasty is the weak and ineffective Enannatum II, of the family of Ur-Nanshe.14 By the year 2370 BCE Lagash’s power began to wane.15 Still, Lagash plays an important role in the transition between the Sumerian period and Akkadian period which begins no later than 2270 BCE within the next 100 years.

Making our way down the list, through the Early Dynastic Period, we eventually arrive at the important “Kug-Bau” (Kubaba) “the woman tavern-keeper, who made firm the foundations of Kish”. Sadly, we don’t know much about her, but she is a woman (the only such one on the kings list)! She is important due to her role as the first ruler of Kish with a - potentially - possible 100 year reign. She appears to have gained independence for Kish from under the thumb of the previously mentioned and excluded from the list, dynasty of Lagash.

Very little is known from her reign, or if she even existed - because she didn’t, why would a grandmother be on a list other than to give legitimacy to her son, or grandson? It even appears the kingship immediately shifts off of Kish to the dynasty at Akshak, but is then taken by Kubaba’s son named Puzur-Suen of the 4th dynasty of Kish around 2350 BCE making it seen like the 4th dynasty inserted her as the 3rd to explain a lapse in records. Other than his 25 year long reign and his son Ur-Zababa, nothing else is known. We have much more extensive information on his son due to his critical role in the rise of Sargon.

Reportedly, Sargon was the cup-bearer for Ur-Zababa, but this role was more than just ceremonial and offered some level of legal jurisdiction over the religious structure. Apparently “Ur-Zababa ordered Sargon in his religious role as his cupbearer, to change the wine libations of Esagila.” which shows a clear relationship to Sargon as a ritual priest before his ascendancy as a king. In many ways this mirrors David HaMelech (The King) and his relationship to Saul showing parallels within their near eastern context.

As mentioned, the Lagash kings are wiped off the list for some reason, or simply left out as a form of propaganda. As a result the list claims the 4th dynasty of Kish had their kingship transferred directly to Uruk when in reality Lagash reasserts themselves momentarily against Ur-Zababa under a king named Urukagina. Sargon, as cup-bearer to Ur-Zababa, would probably have involved himself in these conflicts being the foundational years of his rise to power.

The aforementioned Urukagina would not be very important if not for his “Code of Urukagina” being the earliest discovered legal code. Many erroneously assume this is the Code of Hammurabi, and even scholars presume the Code of Ur-Nammu (written under the time of Ur) was the first legal text, but realistically Urukagina has all of them beat. Obviously, that’s just where archeology stands now, and it’s probable Urukagina got his innovations from an earlier innovation of law discovered around Ebla from only a few years prior.

Whatever the case, Urukagina’s reign is incredibly short lived, and soon after these events came the rise of the similarly brief 3rd dynasty at Uruk led by the famous 𒈗𒍠𒄀𒋛 Lugal-Zagesi. Lugalzagesi ascended to power circa 2296-2271 BCE, in the middle of the Umma-Lagash War over the fertile plain of Gu-Edin where he successfully defeated Lagash, and briefly unified Sumeria.16 What appears to be happening is a sort of inter-Sumerian ethnic rivalry between the dominant cities of Lagash and Umma for rule over the empire. However, the always pressing rival of the Sumerians, the Kishites to the north, continually intruded on events during the Early Dynastic period, culminating in the ascendancy of Sargon the great, of Akkad - himself ethnically related to the Kishites.

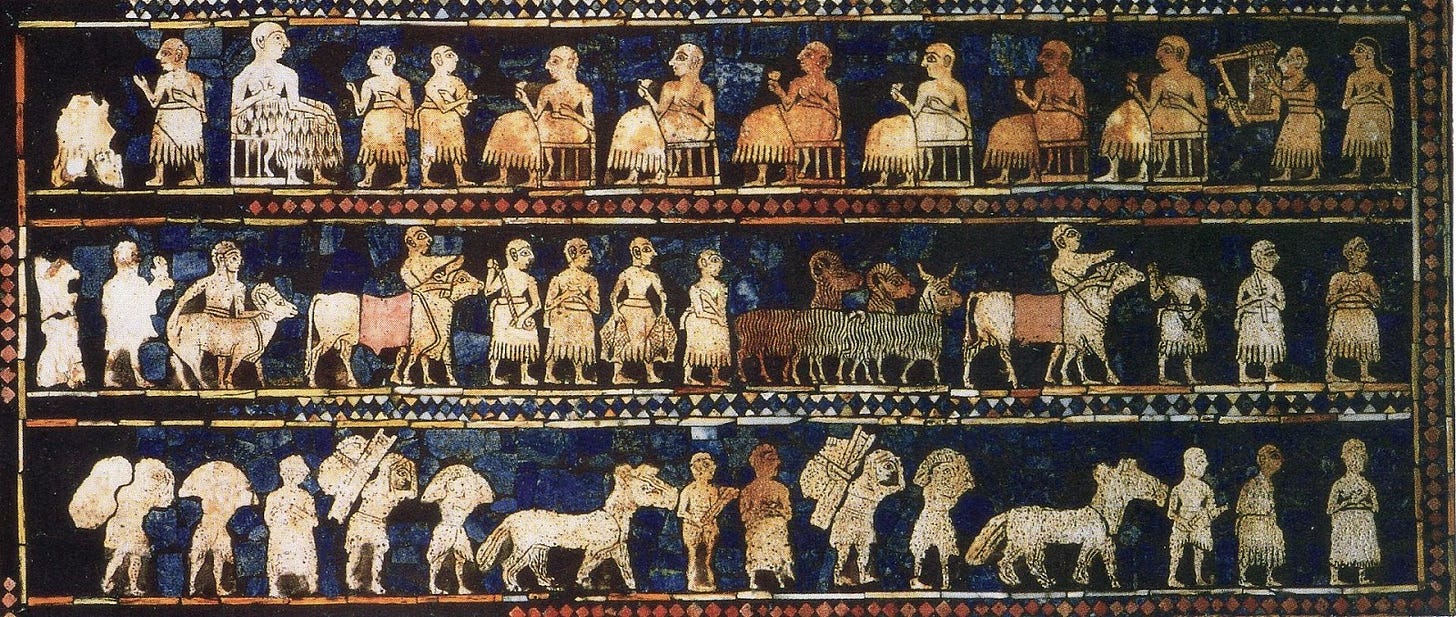

In this ensuing competition between Kish and Uruk - Semitic and Sumerian - Sargon usurps power and defeats everyone. From an inscription describing the event “Sargon, king of Akkad, overseer of Inanna, king of Kish, anointed of Anu, king of the land, governor of Enlil: he defeated the city of Uruk and tore down its walls, in the battle of Uruk he won, took Lugalzagesi king of Uruk in the course of the battle, and led him in a collar to the gate of Enlil.”17 Clear from this inscription is the defeat of Lugalzagesi at the hands of Sargon, but even better we have a depiction of this attached in the figure to the right. In the image we see Lugalzagesi shackled, and being clubbed over the head by supposedly Sargon in a form of execution, or humiliation ritual.18

This marks the end of the pseudo-mythological Early Dynasty period of Sumeiran history, from which point the periodization shifts into one of competing empires laying claim to the regional kingship. The first, and possibly even most important ancient ruler until the time of Hammurabi is the famed “Sargon of Akkad.”

Frayne, Douglas (2008). The Royal inscriptions of Mesopotamia. Early periods, vol. 1, Presargonic Period (2700–2350 BC). Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Sherman Storytelling: An Encyclopedia of Mythology and Folklore p.201

Lormier, M. (2008), Stratigraphies comparées au IIIe millénaire au pays de Sumer. Études de cas de Kish, Nippur et des cités de la vallée de la Diyala, UVSQ

Katz, Dina (1993). Gilgamesh and Akka. SIXY Publications. p.11

Black, Jeremy; Green, Anthony (1992), Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia: An Illustrated Dictionary, Austin: University of Texas Press, pp. 166–168.

Gonzalo Rubio. "Reading Sumerian Names, II: Gilgameš." Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 64, The American Schools of Oriental Research, 2012, pp. 3–16, https://doi.org/10.5615/jcunestud.64.0003.

See e.g. Glassner, Jean-Jacques, 2000: Les petits etats Mésopotamiens à la fin du 4e et au cours du 3e millénaire. In: Hansen, Mogens Herman (ed.) A Comparative Study of Thirty City-State Cultures. The Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters, Copenhagen., P.48

Van De Mieroop, Marc (2004). A History of the Ancient Near East: Ca. 3000-323 BC. Wiley. pp. 50–51.

Hansen, Donald "Royal Building Activity at Sumerian Lagash in the Early Dynastic Period." Biblical Archaeologist. 55.4 (1992): 206-11. Print.

Flannery, Kent; Marcus, Joyce (2012). The Creation of Inequality: How Our Prehistoric Ancestors Set the Stage for Monarchy, Slavery, and Empire. Harvard University Press. pp. 492–493.

Lomazoff, Amanda (2013). "Sumer". The Atlas of Military History. with Aaron Ralby. Thunder Bay Press. pp. 487–488.

Bertman, S. (2005). Handbook to Life in Ancient Mesopotamia. Facts on File Library of world history. OUP USA. p. 84.

Jordan, Michael (1993). Encyclopedia of gods : over 2,500 deities of the world. Internet Archive. New York : Facts on File. pp. 245

Jones, C. H. W. (2012). Ancient Babylonia. Cambridge University Press. p. 34

Radau, Hugo (2005). Early Babylonian History: Down to the End of the Fourth Dynasty of Ur. Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 120

"Middle East & Africa to 1875". Sanderson Beck. 1998–2004. Retrieved 2006-11-27.

Liverani, Mario (2013). The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy. Routledge. p. 143.

Nigro, Lorenzo (1998). "The Two Steles of Sargon: Iconology and Visual Propaganda at the Beginning of Royal Akkadian Relief". Iraq. British Institute for the Study of Iraq. 60: 85–102.

I am certain my research has not gone unnoticed. But what are you trying to prove here? That the traditions recorded in the Torah were actually adapted from some earlier and supposedly more pristine source that had allegedly been revealed by the Babylonian pantheon? We want to avoid barking up the wrong tree altogether...