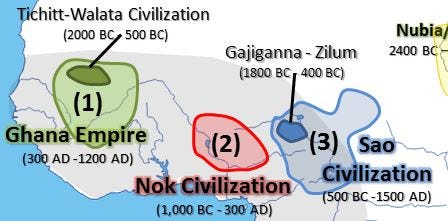

As we discussed, during much of the ancient and classical periods, South Western Africa would have been inhospitable. Curiously, most of the Niger-Congo languages that descend from earlier cultures such as the Sao, or Nok are not found in their more ancient ranges. They pushed south as the climate of West Africa changed, coinciding with migratory pressure of the Amazigh, Hausa and Arabs further north. This suggests a starkly different historical range for this language family, shifted north into the Sahel, better matching the ancient empires found in the region. Thus, none of these people are Dedan, but they are descendants of a “Dedanite”, or “Western Ethiopian” shared culture, and language family.

What is clear about this culture is its emergence as a fusion of the centralized political structure of the Sao city states with the metalurgic trading traditions of the Nok. Both of these elements become staples of West African civilization; with Sao operating as a political model and the blacksmith culture of the Nok becoming the cultural backbone of the region.

One interesting group that claims to be the descendants of the Sao civilization around Chad are the Sara people. Little historical written information on these people are known beyond a shared ethnicity, religion, and the fact they all speak a Nilo-Saharan branch language. However, there is a key piece of information regarding these people that might potentially give us clues to the origin of the Sao. Genetic analysis on the Sara show that they have the closest relation to the Kunama people of Eritrea. Both of these groups are Nilo-Saharan speakers with cultural similarities to West Africans, but biologically distinct from the Cushitic and Semitic speakers of Ethiopia proper.1

Striking about these Kunama is the fact they are settled along none other than the Gash and Setit/Tekeze rivers, putting them and possibly their related Sao brethren well within the sphere of the Israelite world, and curiously right next to where we tentatively identified Raamah. The time frame of the civilizations start between 1800-800 BCE from the Gajiganna substrate, with the height of its power reaching all the way to the 6th century prior to Islamic conquest, and even possibly having lasting cultural impacts up until full Islamic conversion in the 16th century. It has been suggested there was a movement of potentially Hyksos people into Sao, but this is unlikely owing to the Hyksos semitic origins.2 It is more likely that the Sao were a fusion of a foreign wave of migrants across the Sahel with the native Gajiganna culture that was subsumed by the later Sao. If the Kunama link is believed, Sao could certainly be one grouping of the Dedanites, and its trade contacts between Egypt across the Sahel are an extremely likely occurrence.

However, Dedan is less specifically Sao, as the Sao are certainly an ethnically mixed group rather than Niger-Congo, but this does provide some close relation between Nilotes, Semitic Eritreans, Cushites, and Niger-Congo people. Sao may have been a cultural crossroads, and ended up the most advanced civilization owing to its critical location in the Sahelian trade.

Another ancient civilization to the development of the Sahelian trade and the emergence of the “West African Niger-Congoids” was the Nok who pioneered blacksmithing in the region as far back as 1500 BCE.34 Nok most likely came from the north in the Sahel based on the plants they used as crops, such as pearl millet and cowpeas, being indigenous to the Sahel.5 Academics such as Breunig state “"The people of the Nok culture must have come from somewhere else. So far, however, we have not found out what region, though we suspect the Sahel zone in West Africa.”6

We briefly mentioned the Nok as progenitors to the later Igbo and Yoruba cultures, with their innovations in terracotta pottery being critical to their regional dominance, but the Nok’s real innovation was their strong metallurgic science. This tradition of metal working morphed into a religious caste system which saw blacksmiths marrying within their group exclusively, and thus passing on the tradition only to their tribes. This led to a limitation in the number of groups who worked with metal, creating a system of mobile blacksmiths through west africa that would move into areas needing a blacksmith.7 This lifestyle likely dates back to the time of the Nok, and the remnants of the Nok civilizations blacksmiths are found in other tribes throughout the region.

The two most notable groups of blacksmiths are the aforementioned Mande - including their sub group the Bambara - and none other than the Yoruba of Ife and Oyo. Like the Nok, the Yoruba base their existence around ironworking, with iron being a central aspect of their religious traditions. The Ife and Oyo both believe that the blacksmith has the power to express the spirit of Ogun, the god of iron who has interlaced political interactions with Oduduwa.

Like the Yoruba, the Mande also have strong religious traditions affiliated with ironworking. Oftentimes the blacksmith is called by a chief as counsel for major village decisions. The Mande believe that a blacksmiths' power is great due to the control of a force called “nyama” - a force that controls all the energies of the village members.8 Like the Mande, the Bambara have closely related traditions, as well as practices of medicines relating to the spirit of Ogun.

An interesting curiosity is that the Igbo, who also have strong bronze traditions, might actually have independently developed their own traditions of metal working around the 9th century, helping explain their dominant rise. Evidence for this is the lack of common techniques in other metal working cultures such as riveting, soldering, and wire making, suggesting an isolation of their metal traditions.9 As previously mentioned the region of Nsukka has iron smelting furnaces dating to 2000 BCE in Lejja,10 and 750 BCE in Opi,11 suggesting the Igbo were independently working metal separate from the Nok.

How blacksmithing - or metal technology - spread through Africa is unclear, but the similar traditions of the Mande and Yoruba attests to a regional sharing of traditions. As stated it is difficult to know how this progressed, but it’s clear that the Mande as a group formed a separate origin unrelated to this sub caste of metal workers that import that traditions to the Mande.

Most probably descended from ancient Sahelian populations, the Mande’s rise is associated with textile weaving processes such as strip-weaving, and the independent development of agriculture around 4000-3000 BCE, forming the basis of West African farming traditions.12 The name given to this culture is the “Tichitt Tradition” having been formed by mostly Mande people who migrated from Central Sahara,13 potentially not far from the Sao near Lake Chad.

The peak of this civilization was between 2000-500 BCE during the pastoral period of the Sahara and Sahel making it more hospitable for a complex civilization.14 The earliest date for Tichitt is 2200 BCE, predating the Gajiganna or Nok, but by 1800, coinciding with the rose of Gajiganna and coexisting with Nok by 1000 BCE. All three of these civilizations last well past the classical era, and the dating puts them all within a timeframe for Table of Nations inclusion. All three of these cultures simultaneously influenced each other, and possibly shared their traditions through a much more hospitable Sahel, making it challenging to say which would represent a specific identity. However, the Sao and Nok share traditions much more extensively than the Tichitt/Ghana do with the former, making it more likely Sao and Nok group together, or Nok came from Sao.

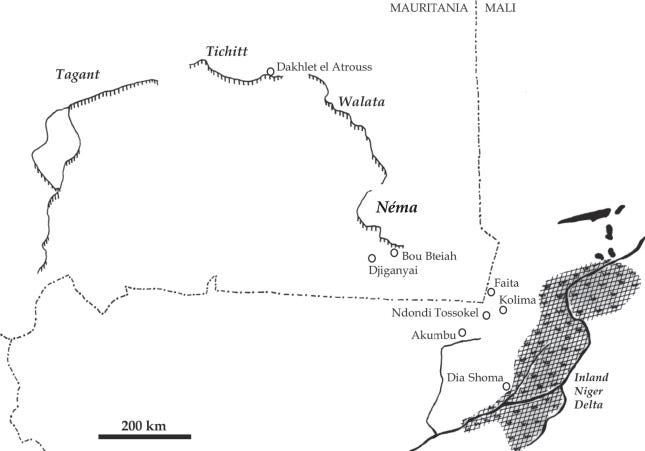

Four main sites of Tichitt culture exist, all with the prefix ‘Dhar’: Dhar Nema, Dhar Tagant, Dhar Tichitt, and Dhar Walata. The word “Dhar” means cliff, referring to the nearly 800 kilometers of rocky escarpments formed by the Tagant Plateau.15 The Tagant Plateau essentially flanks a region called “Erg Aoukar” - sometimes called the “Hodh Depression” - a geological depression that used to act as a drainage basin for the once fertile region. Aoukar acted as the center of the Tichitt culture containing massive lakes serving as an oasis until 1000 BCE.16 According to scholars Tichitt was the earliest complex civilization in West Africa17 serving as a model for state formation in the wider region.18 Increasing desertification due to the final phases of the Greening Sahara results in the migration from the Dhars, towards the Niger not far south east.19

As early as the 3rd or 4th century BCE the Dhar pastoralists began residing in areas around the Niger in Mali, the current site of the modern Mande people.20 Sites such as Macina, Mema, Dia, and Jenne all began their settlement associating with the rapid influx of Tichitt peoples. Based on this it is likely the Tichitt were a proto-Mande people. Around this same time frame the rapid aridization of Lake Mega Chad forced increased migration of Central Saharans towards the Niger, likely forming the ethnogenesis of many of West Africa's modern populations. The sites in Mali take over the previous Dhar sites in terms of importance.

At this point you have likely checked out, but we are really honing into who, or what, Dedan represents. Hopefully you will stick with it, and if you have please leave a comment saying “Still here!” for comedic value.

Excoffier, Laurent; et al. (1987). "Genetics and history of sub-Saharan Africa". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 30: 151–194.

Fanso (1989), pp. 15–19.

Miller, Duncan E.; Van Der Merwe, N.J. (1994). "Early Metal Working in Sub Saharan Africa". Journal of African History. 35: 1–36.

Minze Stuiver and N.J. Van Der Merwe, 'Radiocarbon Chronology of the Iron Age in Sub-Saharan Africa' Current Anthropology 1968. Tylecote 1975

Breunig, Peter; Rupp, Nicole (2016). "An Outline of Recent Studies on the Nigerian Nok Culture" (PDF). Journal of African Archaeology. 14 (3): 242, 247.

Breunig, Peter (January 2017). Exploring the Nok Culture (PDF). Goethe University. p. 24.

Ross, Emma George. "The Age of Iron in West Africa". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Archived from the original on 2002-12-07.

Ross, Emma George. "The Age of Iron in West Africa". The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Ward, Gerald W.R., ed. (2008). The Grove encyclopedia of materials and techniques in art. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 71.

Eze–Uzomaka, Pamela. "Iron and its influence on the prehistoric site of Lejja". Academia.edu. University of Nigeria,Nsukka, Nigeria. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

Holl, Augustin F. C. (6 November 2009). "Early West African Metallurgies: New Data and Old Orthodoxy". Journal of World Prehistory. 22 (4): 415–438.

D.F. McCall, "The Cultural Map and Time Profile of the Mande Speaking Peoples," in C.T. Hodge (ed.). Papers on the Manding, Indiana University, Bloomington, 1971.

Abd-El-Moniem, Hamdi Abbas Ahmed (May 2005). A New Recording of Mauritanian Rock Art (PDF). University of London. p. 210

Brass, Michael (June 2019). "The Emergence of Mobile Pastoral Elites during the Middle to Late Holocene in the Sahara". Journal of African Archaeology. 17 (1): 3

Maurer, Anne-France; et al. (15 December 2014). "Bone diagenesis in arid environments: An intra-skeletal approach". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 416: 18.

MacDonald, Kevin C.; Vernet, Robert; Martinon-Torres, Marcos; Fuller, Dorian Q. "Dhar Néma: From early agriculture to metallurgy in southeastern Mauritania".

MacDonald, Kevin C.; Vernet, Robert; Martinon-Torres, Marcos; Fuller, Dorian Q (April 2009). "Dhar Néma: From early agriculture to metallurgy in southeastern Mauritania". Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa. 44 (1): 3–4, 42.

Brass, Michael (2007). "Reconsidering the emergence of social complexity in early Saharan pastoral societies, 5000 – 2500 B.C." Sahara (Segrate, Italy). Sahara (Segrate). 18: 7–22

Holl, Augustin F.C. (2009). "Coping with uncertainty: Neolithic life in the Dhar Tichitt-Walata, Mauritania, (ca. 4000–2300 BP)". Comptes Rendus Geoscience. 341 (8–9): 703.

McDougall, E. Ann (2019). "Saharan Peoples and Societies". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History. Oxford Research Encyclopedias.