In the last part we looked at the Volga-Congo language family groups in West Africa that could possibly help us in identification of Dedan, but this time we will dig into a sub-group, the Volga-Niger family. The major two groups inside this group are the Yoruba and Igbo of modern Nigeria, who are two of the largest ethnic groups in West Africa. Let us begin with the Igbo.

The Igbo come from “Igboland” (shocking, I know) the lower Niger river region in the south of Nigeria, just before it empties out into the ocean. Igboland is one of the most densely populated regions of Africa, maybe the most dense outside of the Nile, and further north at the confluence of the Niger and Benue rivers is often considered the origin of the Bantu expansion, and point at which most central Africans split off from the west Africans supporting this area being overcrowded. As a result, the region's human presence starts at least 10,000 years ago, with some of the earliest pottery found around 6000 BCE. Anthropologists have discovered the use of monoliths dating to 4500 BC at Ngodo in the Uturu town.1 Most of the early evidence is sparse, indicating a lack of major settlements. The site of Nsukka shows both pottery and metal working between the year's 3000-2500 BCE showing a progressive evolution of the region's settlements towards more complex communities.2

One of the most important Igbo sites is the town of “Igbo-Ukwu” which has over 700 high quality copper, bronze, and iron artifacts showing an extensive level of metal working. These are the oldest bronze finds in Africa, cluing us into this region's early emergence as a center of power.3 However, the Igbo never centralized themselves in a traditional sense, and operated a more informal community of peoples resembling the Greek city states.

While there were no known organized Igbo polities in the region during the classical era, the later Kingdom of Nri arose in the 9th century. Nri was centered around Igbo-Ukwu and the Igboland, ruled by a semi-legendary king named Eri. Eri was sent by the ‘supreme being’ in Igbo mythology from heaven to earth, founding the many peoples and cultural traditions of the Igbo, including their most elite clans of priests and diviners.4 Sadly this story doesn’t provide many clues to anything related to Dedan, making this identification unlikely.

One, potentially major or minor fact depending on your perspective is the existence of the “Igbo Jews”. While at first the existence of Jews in this region is strange, it would be even more strange if somewhere in West Africa - especially its most populous region - didn’t contain a section of Jews when there are so many Christians and Muslims. The existence of Jews in my eyes is less quirky than many of my fellow Jews might believe; when one learns about Khazars, Shanghai Jews, Cochin Jews, or Judeo-Tats the existence of the Igbo is not so farfetched. What is clear though is these people did not maintain Rabbinic traditions, or contact with wider Jewry, putting into question some of their practices and contiguity of their oral traditions.

Accordingly, the Igbo Jews have a legend that positions Eri as one of the seven sons of Gad, one of the twelve sons of Jacob and the eponymous founder of the “Tribe of Gad”. If this were true, then the Igbo are certainly not Dedan at all, however I myself question accounts of any “lost tribes” since there is no evidence found in the Torah for any “lost” tribes, leaving open the possibility of descent from Dedan.

While Igbo sites are not exactly clear regarding archeological information during this period, the Nok culture further north, around that previously mentioned confluence of the Benue-Niger is much more widely attested, and likely serves as the background for many of the cultures in the region. The Nok are closely related to the Gajiganna located around Lake Chad, and may have migrated from Chad near Central Sahara, but could have just as easily migrated from the West African Sahel.5 The Nok culture's more ancient origins around 1500 BCE help support a potential inclusion in the Table of Nations.6 The Nok were proficient artisans of terracotta, and this extensive usage is likely to have influenced the later cultures in the region, such as those at Ghana, Mali, and Ile-Ife.7

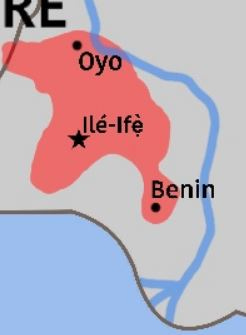

Nok was a major influence on the Yoruba through their ancient capital Ile-Ife. The actual kingdom centered around Ile-Ife was Yoruba, speaking the same language and sharing common ethnicity with the Yoruba, but the designation “Yoruba” had yet to come about potentially being a term borrowed from Europeans, or Hausa. The likely origin of this term is as a greeting for the ‘Yoruba’, and Hugh Clapperton’s travel books suggest that “Yourriba” was a customary way of greeting the Yoruba King of Oyo.8

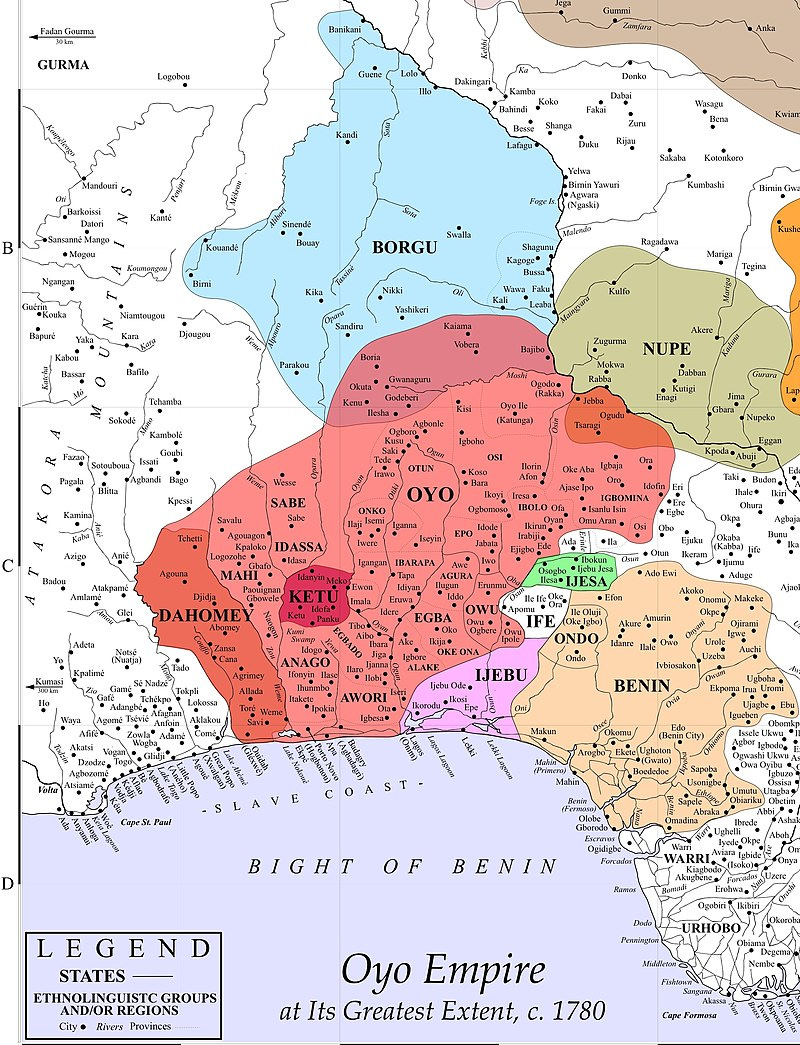

Oyo was one of the more major empires in the region from the 14th through 19th centuries centered around the traditional Yorubaland. It dominated its neighbors and most of the region speaks similar languages to Yoruba, including the Igbo. The Edo of the Benin Empire are closely related to the Yoruba, as are the Fon of the Kingdom of Dahomey (Dahomey is actually modern Benin, and Benin is located inside modern Nigeria). All of these states as “Greater Yoruba peoples” coalesced and splintered during the Oyo Empire.

The Oyo Empire’s origins are unclear except for oral traditions that claim that Oyo was founded by the last Ife princeling named “Oranyan” or “Oranmiyan” to some foreign groups. Interestingly Oranyan is claimed to have had a “two-tone complexion” attributing meaning to his name when translated meaning “The child has chosen to be controversial”. Again we see usage of color motifs in African traditions. Oranyan’s alternative name was Odede - most likely his birth name - which means “Great Hunter”. While dated much later, and likely unrelated, his name does retain the curious “de-de” we would be looking for to identify someone as Dedan. If sources are correct, when an “O” is placed before a word in Yoruba it implies “he, she, you or it” making it possible Semitic speakers dropped such a repetitious sound when translated a name over to Hebrew. Afterall, Hebrew words will often do the same with words such as “the” or “of” and felt it redundant to list the name with its O sound. Potentially we could be looking for an “Odedan”.

“Ode” is a word often used to denote places, or temporal locations such as in “ode - aye” meaning “the outside world” or “ode oni” meaning “today.” Is there a possibility the “Ode-da” meant something similar? Words like “Odidi” mean complete, and “Ododo” mean justice. An extremely high number of critical words in Yoruba have this “O” sound at the start, making this less than a tenuous theory regarding linguistic shift.

We will see soon why this is unlikely, but to play devil’s advocate it is possible “Great Hunter” was some sort of generic title or name, often reused as a personal name in later periods. Why do current Yoruba traditions assign him and his family as founder of the Yoruba; who did Oranyan believe were his ancestral people? He certainly didn’t believe he was the start.

This supposed Oranyan was the son of Ogun, himself the son of the Oba (King) of Ife named “Oduduwa”. Oduduwa is considered the progenitor of the majority of the Yoruba peoples, even those not directly from Oranyan, and again shares this “D-d-” sound. His name has a very different translation meaning “The great repository which brings forth existence” heavily implying he was a founder of a people group. Indeed certain groups such as the Gobir, Borgu, or possibly even the aforementioned Kanuri claim their ancestors were Oduduwa’s brothers.9

Just south of Ife was the Kingdom of Ijebu - considered a sub-tribe of Yoruba people - which contains a curious system of defensive structures called “Sungbo’s Eredo”. This massive construction of walls and ditches was built around the year 800 AD in honor of the Ijebu noblewoman Bilikisu Sungbo.10 As the name Bilikisu implies, she is tenuously linked to the Queen of Sheba, also called “Bilqis” in certain legends. While this link seems very strange, we cannot discount it owing to the historical Queen of Sheba being definitively “Ethiopian”. If this region was considered “Western Ethiopia” there is no reason to discount a potential shared tradition for Bilqis and the “Queen of Sheba” who might have been also a “Queen of Dedan”. Lack of good archeological evidence around Sungbo’s Eredo prevents us from taking this link any further.

Another weak link tying the Yoruba with distant cultural traditions in the middle east might be the motif of “Solomon’s Knot”. Obviously, this could very easily be a later introduction, but the Yoruba specifically often portray this symbol on glass beadwork, textiles, and carvings. They use it to denote royal status, of all things, and it is prominently featured in crowns, tunics and various ceremonial objects. The previously discussed Akan also stamp this symbol on their sacred Adinkra cloth. However these meanings differ from Judaic usage where it symbolizes eternity and thus often used on tombstones, and in Jewish graveyards.

If we are to take this motif at face value, is there the possibility that Solomon stamped this symbol on some sort of document that the Queen of Sheba, or Bilqis, took back with her? Is such a theory completely farfetched, knowing the great trans-saharan traders ability to transmit cultures across the Sahel in a lateral fashion? They would not have transmitted writing since the complex linguistic make up of the Sahara made other forms of communication more useful, visual symbols possibly being part of this system. For argument's sake, a contrarian would claim this could be a later introduction of the Arab era meant to legitimize descent, rather than connected to the actual traditions of Israel and Solomon.

Returning to the origin of the Yoruba, their holy city of Ile-Ife is considered the center of the empire's culture. Indeed prior to the Oyo Empire’s rise in the 14th century, the Empire of Ife, centered around Ile-Ife, was the dominant force in the region. This is the actual empire that Oduduwa founded, as well as the cities of Oyo and Benin. Oduduwa was considered a deity in the Yoruba religion, but this practice is actually a form of deification of real figures, bringing them up to the level of gods and associating them with previously known deities; a common tradition in West Africa. Reportedly this period was as early as the 10th century, but this is still extremely late relative to our timeframe, making Oduduwa, or his son “Odede” unlikely candidates for Dedan. What is more likely is that this cultural scheme and naming system was imported from beyond, making the Yoruba, and the broader Volta-Niger languages descended from Dedan.

Link to the next post

We will continue this in the next section. Hopefully your picture of West Africa is much deeper than it was before reading. Thank you once again.

Oliver Ifeanyi Anyabolu, Nigeria, past to the present: from 500 B.C. to the present (2000), p. 12.

Apley, Alice (October 2001). "Igbo–Ukwu (ca. 9th century)". Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved December 15, 2014.

Worship as Body Language By E. Elochukwu Uzukwu

Breunig, Peter (January 2017). Exploring the Nok Culture (PDF). Goethe University. p. 24.

Champion, Louis; et al. (15 December 2022). "A question of rite—pearl millet consumption at Nok culture sites, Nigeria (second/first millennium BC)". Vegetation History and Archaeobotany.

Ramsamy, Edward; Elliott, Carolyn M.; Seybolt, Peter J. (January 5, 2012). "Part I: Prehistory To 1400". Cultural Sociology of the Middle East, Asia, and Africa: An Encyclopedia. SAGE Publications. p. 8.

Hugh Clapperton (1829). Journal of a Second Expedition Into the Interior of Africa; to which is Added the Journal of Richard Lander from Kano to the Sea-Coast. John Murray. p. 41.

History of the Yorubas by Samuel Johnson 1921

Stone, Peter G. (2011). Cultural Heritage, Ethics and the Military. Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-538-7.