Unlike Arioch, Chedorlaomer is a much more substantial figure with a well known identification for his Kingdom of Elam. No tricks here, we are looking strictly for a king of Elam, sometime around the era of Hammurabi possibly even within a 100 year range. However, if we remember from previous sections Chedorlaomer was leader of a coalition that Hammurabi fought under, putting him as the leader of a large regional polity surpassing Babylon. Babylon was mostly an unimportant city until the time of Hammurabi, with Elam and Larsa being far more important cities, giving good reason for why Amraphel was not the primary King in the alliance in that period.

In the Tur HaArokh we have a brief reference to the order of the kings listed and why Cherdorlaomer is not first despite being leader, and mentioned more frequently than Amraphel. “Although Kedorleomer was the heavyweight among these Kings as we know from verses 4 and 9 in which he is always mentioned as the major figure, the other Kings being his subordinates, “the Kings who were with him,” in this instance Amrafel, is mentioned first, perhaps because he was senior in years,”1 Funny enough we see a similar instance to the Shem, Ham, Japheth dispute of birth order, but there is the new information that Amraphel was “senior” to Cherdorlaomer in some capacity. Was it spiritual, political, or based on their ages?

Expanding on this war we once again have the uncertain source of the Sefer HaYashar where it expounds upon this war as a “War between the families of Ham”. “At the same time there was a war between the families of the sons of Ham, who dwelt in the land that they built up for themselves. For Chedorlaomer king of Elom, one of the families of Ham, went forth and made war upon the other families of Ham, and he vanquished them under his hand, and he also subdued the five cities of the plain, and all were under his hands in dependence and servitude for twelve years, paying him tribute year after year.”2 Now this is immediately strange for a couple of reasons.

Chedorlaomer and Elam are here called ‘one of the families of Ham’ calling into question if this Elam is the same as the Elam, son of Shem. This could be an Elam, son of Ham, which would make more sense, but makes identifying a second Elam a difficult task we will leave for our sections on Shem. Ultimately this Chedorlaomer might have been a Hamite leading the Elamites similar to how Hammurabi and other Amorites were grouped with the Hamites despite being Semitic speakers. This isn’t that strange, and Abraham himself was dwelling in Shinar despite being a son of Shem with his own father Terah being involved as a general of Amraphel during the war. There were Semites leading parts of the coalition within this “War of Hamites”.

Later in the Sefer HaYashar after the war between the families of Ham is completed we are given a separate ‘war’ that first begins as a rebellion among the people of the plain of Shinar. “Therefore when Nimrod heard that the people of the plain revolted against Chedorlaomer, Nimrod hastened to make war against him, and he came full of pride and contempt.”

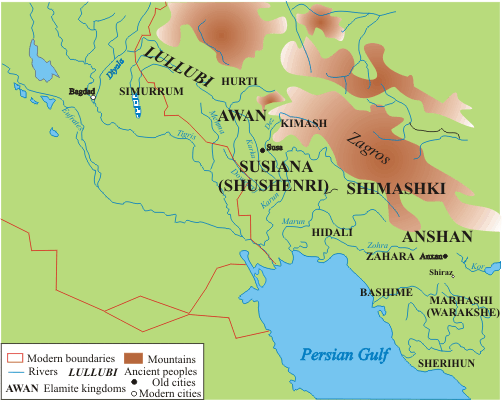

The Sefer continues by giving what seems like a very specific mystical number for the number of combatants serving in the army “And Nimrod assembled all his princes and servants, about seven thousand men, and he went against Chedorlaomer. And Chedorlaomer came to meet him with five thousand men, and they prepared for the fight in the valley of Babel, which is between Shinar and between Elam.” This next part also clues us into the location of the war at the “valley of Babel” located “between Shinar and between Elam”. Odd, given that Babel is not between these two locations, unless Shinar here is viewed to include the northern areas such as Assyria and Mari - who were both notably with Hammurabi during his wars against Elam.

Continuing “And all those kings engaged in battle in that place, and Nimrod and all his people were humbled before the men of Chedorlaomer, and there fell in that battle of Nimrod's men about six thousand. And Mardon the son of Nimrod was among the slain. And Nimrod fled and returned unto his country in shame and contempt. And he was subject to Chedorlaomer for many days.”3 Finishing off the ‘rebellion’ we hear about Nimrod not only losing six thousand of his seven thousand men, but among those slain was his son Mardon. The final piece informs us that Nimrod becomes a direct subject to Chedorlaomer, maybe giving us a direction for who this figure was historically; someone who ruled over Hammurabi as his subject.

There is one problem with everything we’ve just learned, just slightly, given that the Sefer HaYashar really cannot be treated as a certified historical source of any kind. Even if it was recording truths, we can’t hope to understand what they are actually in reference to, or if they are actually a chronicle of the physical events as they happened. What this does though is reaffirm the order of events as: Chedorlaomer rules over Mesopotamia for twelve years > followed by thirteen years of rebellion, or civil war involving Amraphel > culminating in the final conflict with Abraham.

Looking at the actual events as relayed to us through Genesis 14 we see a war between the four kings and the five kings in the valley of Siddim, known today as the sea. It appears all of these eight rulers were dominated by Chedorlaomer for twelve year's, followed by thirteen years of rebellion. It appears this time frame is twelve plus thirteen making a total of twenty five and in the twenty sixth year, or fourteenth after the thirteen years of rebellion, Chedorlaomer comes to Siddim to make war.

There is a slight issue here given that the text isn’t clear if there was an initial war, followed by rebellion war, and then again a battle in Siddim against Abraham corresponding to the events of the Sefer HaYashar, or if there was only a single war. I would lean toward the three separate conflicts angle with the caveat of an implied initial war between Amraphel and Chedorlaomer not actually listed in the Torah, but given to us by the Sefer HaYashar.

There are a series of locations provided in the text between lines 5-8 for the cities plundered by Elam during the war. This list includes: The Rephaim in Ashteroth Karnaim, the Zuzim in Ham, the Emim in Shaveh Kiriathaim, the Horites in their mountain Seir (until the plain of Paran along the desert), the Amalekites in Kadesh at the site of Ein Mishpat, and the Amorites at Hazezon Tamar. Ultimately this is a complex list of nearly all the people in Canaan represented in some form, having Hamites, Shemites, possible Japhethites and even the Rephaim who were known as descendants of the giants. The implication here is that despite Chedorlaomer’s control over the world, there was stark resistance from nearly all peoples who were with Abram in his war.

Turning our attention away from the geopolitical context we can break down the name “Chedorlaomer” into two parts. In Elamite these components would become “Kudur” and “Lagamer” giving us a meaning close to something like ‘servant of a goddess’ specifically the Goddess known as Lagamer in the Elamite pantheon.4 If the Torah was recording mythology it wouldn’t have so accurately labeled the name of Chedorlaomer from the ancient dead Elamite language which no one had been able to translate until modern times.

Affirming this is actually the Rabbinical sources in Chullin 65a:2 where the Gemara asks “If that is so, [what about the name:] “Chedorlaomer” (Genesis 14:4), which the scribe splits in two [so that it appears as: Chedor Laomer? Is it] also [true there] that they are two names? [The verse is clearly referring to only one person.] They say [in response:] There, [with regard to Chedor Laomer, the scribe] splits [the name] into two words, [but he] may not split it into two lines [if the first half nears the end of one line.] But here, he may split [the name bat ya’ana] even into two lines, [indicating that they are completely separate.]”5 In what might be the first for some readers we actually get a scribal note that the name Chedorlaomer, while it can be split into two words, cannot be separated into different lines and must appear ‘together’ confirming it as a proper name, or title.

There is the problem of the suspicious Spartoli tablets where a supposed Kutir-Nahhunte II is reportedly represented by Kudur-lagamar.6 This Kutir-Nahhunte II was actually a later king of Elam from around 1150 BCE, but might help us confirm the name in relation to an earlier Elamite king also named Kutir-Nahhunte of the Sukkalmah dynasty from between 1900-1750 BCE around the reign of Hammurabi.7 Again, there is the chance Hammurabi specifically is not Amraphel, but rather his son, family, or dynasty of Babylon in that era. The actual date is less specifically important than the timeframe that these events are occurring inside.

The actual name of the Sukkalmah dynasty comes from their title Sukkalmah meaning “Grand Regent”, showing again this passing of dynastic titles within a ruling lineage. During this same period conflicts between the Isin-Larsa dynasty and Sukkalmah were fierce, and it was during the reign of the Sukkalmah king named Siruk-tuh that Hammurabi first began ruling in Babylon.8 Rulers such as Siruk-tuh were referred to as ‘father’ and ‘great king’9 - a term similar to king of kings - by rulers of Mesopotamia, being the only rulers other than native Mesopotamians to have been addressed with this status above their own.10 We even have the ruler Siwe-Palar-Khuppak having risen to the most powerful ruler in the land with Zimrilim of Mari, Shamshi-Adad I of Assyria, and even Hammurabi himself referring to him as “father” in ancient records.

Critical to our understanding of ancient polities is really the concept of blood lineage that is hinted at with this title of ‘father’ given to the leaders of regional kingdoms. Oftentimes political dynasties and alliances were secured, or maintained, by familial relation. This is not only a practice of Egyptian Pharaohs who would take the princesses of other kings as wives to solidify peace between nations, but also a practice seen with David and Solomon. This is also why it was often brothers, uncles, and nephews that were the largest threat to a king's power being the only ones close enough to be trusted with military leadership. While Amraphel was an unruly follower of Chedorlaomer, the question is begged why Arioch would follow Chedorlaomer without a similar conflict?

Was Arioch related to Chedorlaomer? Perhaps not directly, but if we are going with Rim-Sin (or his brother) as our identification of Eri-Aku - otherwise known as Arioch - then despite the Akkadian name ‘Rim-Sin’ he was actually of Elamite descent.11 If Arioch and Chedorlaomer were both Elamites, then it goes to explain the cause for this alliance and Arioch’s steadfast support for Chedorlaomer even when Amraphel rebels with other kings.

Despite this alliance, both Larsa and Isin during the Isin-Larsa period tried numerous times to take over Susa, capital of the Elamites. This might explain why the Elamites increasingly take interest in Mesopotamia being forced to intervene in local politics. Perhaps this is why Elam felt the need to install a dynasty over Larsa, ultimately with Rim-Sin himself undermining the previous alliance between Isin-Larsa, and his brother rerouting various canals to drain the city of water supply. These Elamites kept mingling in local affairs until none other than Hammurabi - allied with the king of Mari, Zimri-Lim - defeated what was perhaps a coalition led by Siwe-Palar-Khuppak, overthrew Rim-Sin of Larsa, and established what we know as the Babylonian Empire.

Extremely strange is that Siwe-Palar-Khuppak doesn’t die, and continues ruling in Elam with various steles of conquest being made to his name detailing his enlarging of the Elamite empire after the defeat at the hands of Hammurapi.12 Later Elamite texts support this claim, calling Siwe-Palar-Khuppak one of the greatest men in Elamite history. If he did nothing but oversee a collapsing Elam this would be odd, implying that Siwe-Palar-Khuppak was fairly competent despite losing to Hammurabi. If he, or his descendants were Chedorlaomer it might explain the earlier question of why Chedorlaomer is treated with such importance in the Torah with far more detail than Amraphel.

During the reign of Siwe-Palar-Khuppak he actually was sending letters all the way out to Hazor in Canaan, Emar and Qatna in Syria, and the important city of Mari showing his extensive reach, with all of these cities probably falling under his rule in some fashion.13 Not only was his empire stretching across a vast territory deep into Canaan - potentially certifying a Chedorlaomer’s presence in the valley of Siddim - Siwe-Palar-Khuppak even formed a coalition with Hammurabi and Zimri-Lim of Mari. He leads this coalition against Eshnunna, dominating the city and placing his sukkal named Kudu-zulush as official of the city.14

It is only when Siwe-Palar-Khuppak attempts to bring Babylon under his direct control that Hammurabi turns against this coalition, providing direct historical support for the rebellion of Amraphel against Chedorlaomer. The question then becomes about explaining why these names do not line up with the ones recorded in Hebrew?

Why should they? What exactly presupposes a name to be identical with its historical counterpart? Even ancient rulers changed their name, and accepted various titles. Abram becomes Abraham, Sarai becomes Sarah and their grandson Jacob totally changes his name to “Israel”. Joseph is named Zaphenath-paneah in Egyptian, with no seeming reason for this name difference. Solomon is even given the name Jedediah at birth, showing that even “Solomon” might have been a regal title. So why any difference for ancient rulers?

In addition we have seen dozens and dozens of examples all through this discussion of Nimrod of various rulers using a title passed down from previous kings, or even taking their fathers name. It’s extremely probable that the names of these kings varied in history, even if there were titles similar to the names we are given in the Torah. It’s just as likely the Torah changed their names, or altered them in some form as we know from the historically verified “Nebuchadnezzar” whose actual name was something like Nabû-kudurri-uṣur and was changed by - most probably by someone like Ezra - to something resembling “Nabu, protect the mule”.15 Rulers such as Nebuchadnezzar himself actually used a sort of patronymic naming system where children would inherit the name of their ancestors, in this case named after Nebuchadnezzar’s grandfather of the same name.16

What is likely is that the discussed Chedorlaomer tablets from the Spartoli collection have been corrupted by Elamite rulers in some form, inserting their campaigns in the chronicle from much earlier periods. Whether that text refers to the first Kutir-Nahhunte, or the second one is unclear. That same text mentions an Eri-Aku, and Tudhula making it plausible this story was corrupted in some form. The Elamites might have entered later rulers such as ‘Chedorlaomer’ - known as Kutir-Nahhunte, or a possible Kudur-Lagamer - as titles in the place of Siwe-Palar-Khuppak viewing Kutir-Nahhunte as a reincarnation of sorts of his archetypal ancestor.

We mentioned previously the Elamite tendency to carry off Babylonian stele and statues attempting to rewrite history in their favor by muddying the ancient picture. The notable Shutruk-Nakhunte, who himself was followed by an heir called Kutir-Nahhunte, had carried off Hammurabi’s Law Code to Elam with numerous other objects. He had a tendency to add his name to the steles and to the degree at which he inserted himself into ancient stories is unclear.

Shutruk-Nakhunte loved carrying off steles, evidenced from another extremely important historical record known as the Victory Stele of Naram-Sin created around 2250 BCE in the city of Sippar. Despite Shutruk-Nakhunte’s much later rule nearly one thousand years after Naram-Sin, he felt the need to carry off this stele likely due to its depiction of Naram-Sin leading forces against the Lullubi mountain people of the Zagros north of Elam. Shutruk-Nakhunte himself was a descendant of the Lullubi, and this act would likely have made other Lullubi quite loyal to his ideals.

Interesting is one of the final kings of Kassite Babylon named Enlil-nadin-ahi from around roughly 1157 BCE. This king was proclaimed “King of Sumer and Akkad” for around three years17 probably in defiance of occupying Elamite forces.18 During Enlil-nadin-ahi’s father’s reign the Elamites attacked under Shutruk-Nakhunte, leaving his son, none other than Kutir-Nahhunte II - mentioned earlier in connection with the name “Chedorlaomer” - as ruler of Babylon. This confirms there was a ‘Chedorlaomer’ who ruled Babylon in service of Elam.

The reign of Enlil-nadin-ahi is cut short when he makes war against what is now the king of Elam, Kutir-Nahhunte II, being crushed in battle and deported in chains to their capital Susa.19 The point of all of this is to show that Elamites, under a potential Chedorlaomer, may have inserted his name into a record of a previous Siwe-Palar-Khuppak, or a similar variant of explanation.

Tur HaArokh, Genesis 14:1:1

Sefer HaYashar Noach 18

Sefer HaYashar Noah 28-29

Kitchen, Kenneth (1966), Ancient Orient and Old Testament, Tyndale Press, p. 44

Chullin 65a:2

Hindel, Ronald (1994). "Finding Historical Memories in the Patriarchal Narratives". Biblical Archaeology Review. 21 (4): 52–59, 70–72.

Edwards, I.E.S.; Gadd, C.J.; Hammond, N.G.L.; Sollberger, E. (1973). The Cambridge Ancient History (3rd ed.). Cambridge: University of Cambridge. pp. 263–265.

De Graef, Katrien. 2018. "In Taberna Quando Sumus: On Taverns, Nadītum Women, and the Cagum in Old Babylonian Sippar." In Gender and Methodology in the Ancient near East: Approaches from Assyriology and beyond, edited by Stephanie Lynn Budin et al., 136. Barcino monographica orientalia 10. Barcelona: University of Barcelona.

Potts, Daniel T. 2012. "The Elamites." In The Oxford Handbook of Iranian History, edited by Touraj Daryaee and Tūraǧ Daryāyī, 43-44. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Charpin, Dominique. 2012a. "Ansi parle l' empereur' à propos de la correspondance des sukkal-mah." In Susa and Elam. Archaeological, Philological, Historical and Geographical Perspectives: Proceedings of the International Congress Held at Ghent University, December 14-17, 2009, edited by Katrien De Graef and Jan Tavernier, 352. Leiden: Brill.

Amanda H. Weavers, Scribes, and Kings: A New History of the Ancient Near East. Oxford University Press, 2022. 269.

Edwards, I.E.S.; Gadd, C.J.; Hammond, N.G.L.; Sollberger, E. (1973). The Cambridge Ancient History (3rd ed.). Cambridge: University of Cambridge. pp. 263–265.

Kitchen, Kenneth (1966), Ancient Orient and Old Testament, Tyndale Press, p. 321

Van de Mieroop, Marc (2005). King Hammurabi of Babylon. Malden, Ma: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 16–30

Wiseman, Donald J. (1983). Nebuchadrezzar and Babylon: The Schweich Letters. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 2–3.

Nielsen, John P. (2015). ""I Overwhelmed the King of Elam": Remembering Nebuchadnezzar I in Persian Babylonia". In Silverman, Jason M.; Waerzeggers, Caroline (eds.). Political Memory in and After the Persian Empire. SBL Press, pp. 61–62.

Kinglist A, BM 33332, column 2, line 15.

D. J. Wiseman (1975). "XXXI: Assyria and Babylonia, 1200-1000 B.C.". In I. E. S. Edwards (ed.). Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 2, Part 2, History of the Middle East and the Aegean Region, c. 1380-1000 BC. Cambridge University Press. pp. 446, 487.

Elizabeth Carter; Matthew W. Stolper (1985). Elam: surveys of political history and archaeology. University of California Press. p. 40.