One of the most frequently mentioned names in Tanakh is Tarshish, the eponymous second son of Javan. In 1 Kings1 it is mentioned that Solomon had a “fleet of ships of Tarshish”, and later in 1 Kings 22:49 it states “Jehoshaphat made ships of Tarshish to go to Ophir for gold; but he did not go, since the ships were broken at Ezion-Geber.” Isaiah so frequently mentions Tarshish in the context of ships it would be redundant to list them all. While there might be a tendency to use these passages as clues for Tarshish’s location, it would be fruitless to do so since Tarshish’s usage in the later period of Israelite Kings becomes synonymous with the word for ships.

However, we do get mention of a “Tarshish” in reference to a location rather than ships. In Jeremiah 10:9 “Silver beaten into plates is brought from Tarshish, and gold from Uphaz, the work of a craftsman and the hands of a smith; their raiment is blue and purple, all of them the work of experts.” Uphaz is not Ophir, but Phasis, a major trading port town on the coast of the black sea in Georgia. The first record of Uphaz is as a river in Hesiod’s Theogony around 700 BCE, which correlates to the Semitic word Uphaz meaning “a gold river”. Phasis, like Tarshish, was a mixed Greek city, with a ‘barbarian’ core. Interestingly it appears as a critical element of trade from India, through the black sea, attested to by authors such as Strabo and Pliny.

The “raiment is blue and purple” could potentially be referenced to the Phoenicians due to these colors being the principal colors produced during the Phoenician dye process. Tyrian purple is commonly known, but a blue dye called “Techelet” was also used, most often by the Israelites in their Tzitzit. Debate over production of this dye continues, but some still use the color for modern Tzitzit believing we have discovered the true origin of the dye. While typically “Tyrian” purple is associated with the Phoenicians there is no conclusive evidence the Phoenicians invented this process. Indeed, archeological evidence confirms sites predating Phoenicians from Crete, located in Minoan settlements, show signs of the production of dye on the island.23 Other sites from the 18th century in Coppa Navigata, southern Italy, also indicate signs of the dyes' presence.4 If the Phoenicians were not originators of the tradition, it is likely they got their name from trading so heavily in the dye.

An additional reference in Ezekiel 27:7 mentions “blue and purple from the isles of Elishah'', showing that even in Jewish tradition blue and purple came from isles, not from Phoenicia proper. In later periods, after the disappearance of Phoenicians, it is the Greeks who continue the dyeing tradition and the majority of dye production sites are located in Greek settlements. The Phoenicians would have traded for dyes and ore, worked the metals, and been the dyers and smith middle men refiners on the way to Israel. As a result there can be no dispute that this reference clearly places Tarshish as a center of metals trade in the ancient world. There is even tradition in the Torah based on readings of Exodus 28:205 that the gemstone on the priestly breastplate given the name “Tarshish” represents the Tribe of Asher.

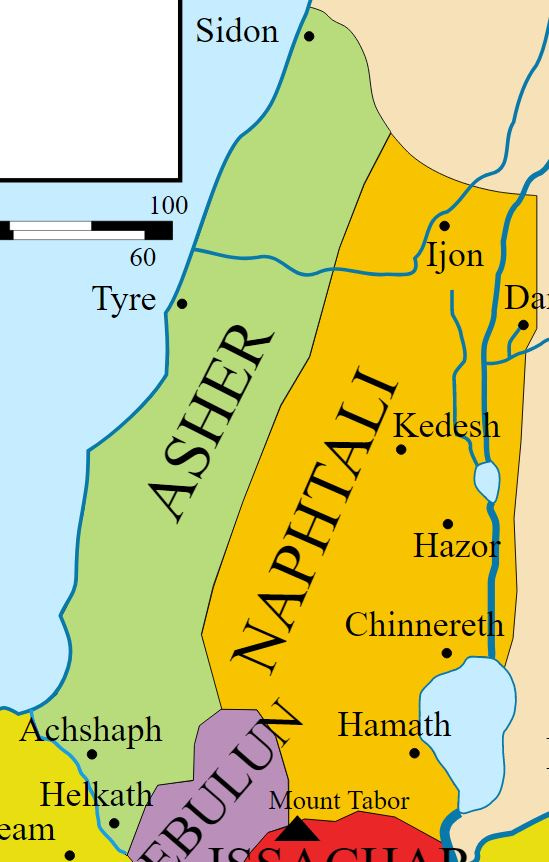

The nail in the coffin for the Asher connection happens after looking at a map of the territory given to Asher in the Torah. Both Sidon and Tyre, the two co-capitals of the Phoenician world, were located directly in Asher, linking the Phoenicians and the Tarshish metal’s trade. Later when we arrive at the Tribes of Israel we will see how this association becomes increasingly important.

It is not just the Tanakh that mentions Tarshish but also a variety of archeological records from the previously mentioned Akkadian inscriptions of King Esarhaddon and the oldest Phoenician inscriptions on the Nora Stone located on the island of Sardinia. The Nora Stone might be the most striking evidence for Tarshish, as the story begins “b’trss” or “At Tarshish” followed by “wgrš hʾ” which means “he drove them out”. Next it follows “bšrdn” meaning “in Sardinia” with the next lines reading “he is now at peace”. This story tells of a Phonician general who conquered the city of Tarshish, on the island of Sardinia. Interestingly the story ends with reference to a Pummay, spelled “pmy” in the text, restored by professor Frank Moore Cross as “pmytn”, a possible reference to the legendary Phoenician Pygmalion from Ovid’s Metamorphoses.

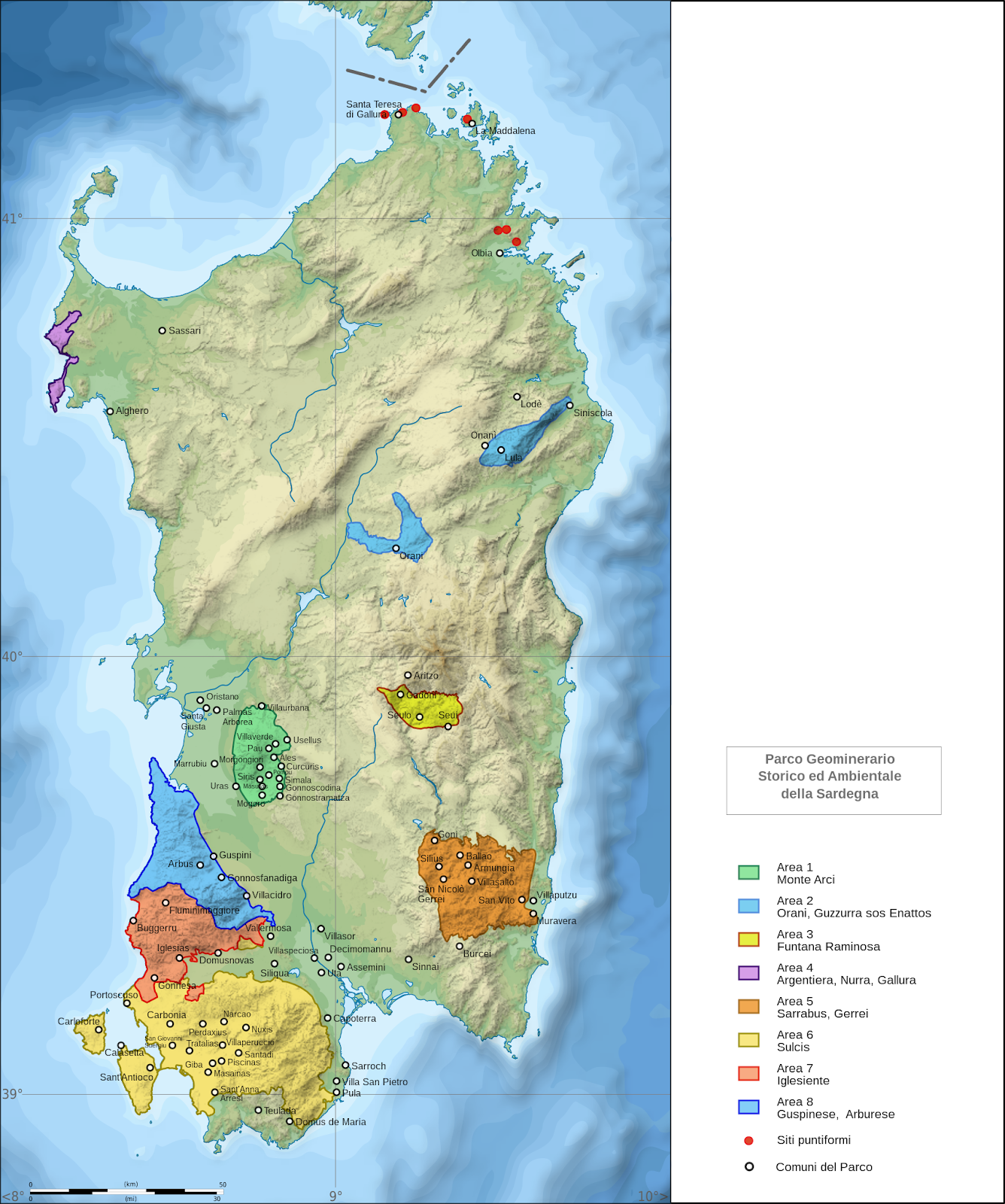

The geopolitical context behind the conquest of Sardinia is set during the Early Iron Age expansion of the Phonician thalassocratic empire. While at first tempting to assume the settlers of Sardinia were natives, a tendency often presumed in absentia of archeological evidence yet to be uncovered, the actual rulers of the island were the “Nuragic” civilization starting from 1800 BCE onward. The Nuragi came from the mainland, clashing with, and forcing out, the natives of the area. While the old pre-Nuragic still occupied the mountainous regions, the Nuragic tribe of the “Ilienses” (or Iolaes) dominated the Southern half of the island. Immediately the “Io” Greek is preserved, potentially linking them as a remote relative of Greeks. If we assume this is the location of ‘Tarshish’, then Tarshish would, and should, be distantly related to the Greeks.

Indeed this is what we find, with ancient writers such as Pausanius claiming these Greek colonists of Sardinia were repeatedly invaded by Carthaginians (Phoenicians) and Romans, to no avail.6 Till this day we see remnants of a splintered population, and mountain tribes with different traditions from those in the lowlands. Many of these ancient cultural lines still exist on the island today, indicating that while Phoenicia did conquer the island, it still would have been culturally “Greek”, and classified under Javan’s children.

An important clue to unraveling the mystery of Tarshish rests in the persistent references to metals and the distant trade of said metals that Phoenicians were involved in dealing. Conveniently the island of Sardinia was a major exporter of metals such as tin, copper, and silver, whether through Spain or mined on the island, lending credence to the theory that Sardinia is the island of Tarshish. Even more importantly while the previously mentioned pre-phoencian populations still resided on the island, the majority of mineral deposits came from the southern half territory that was colonized.

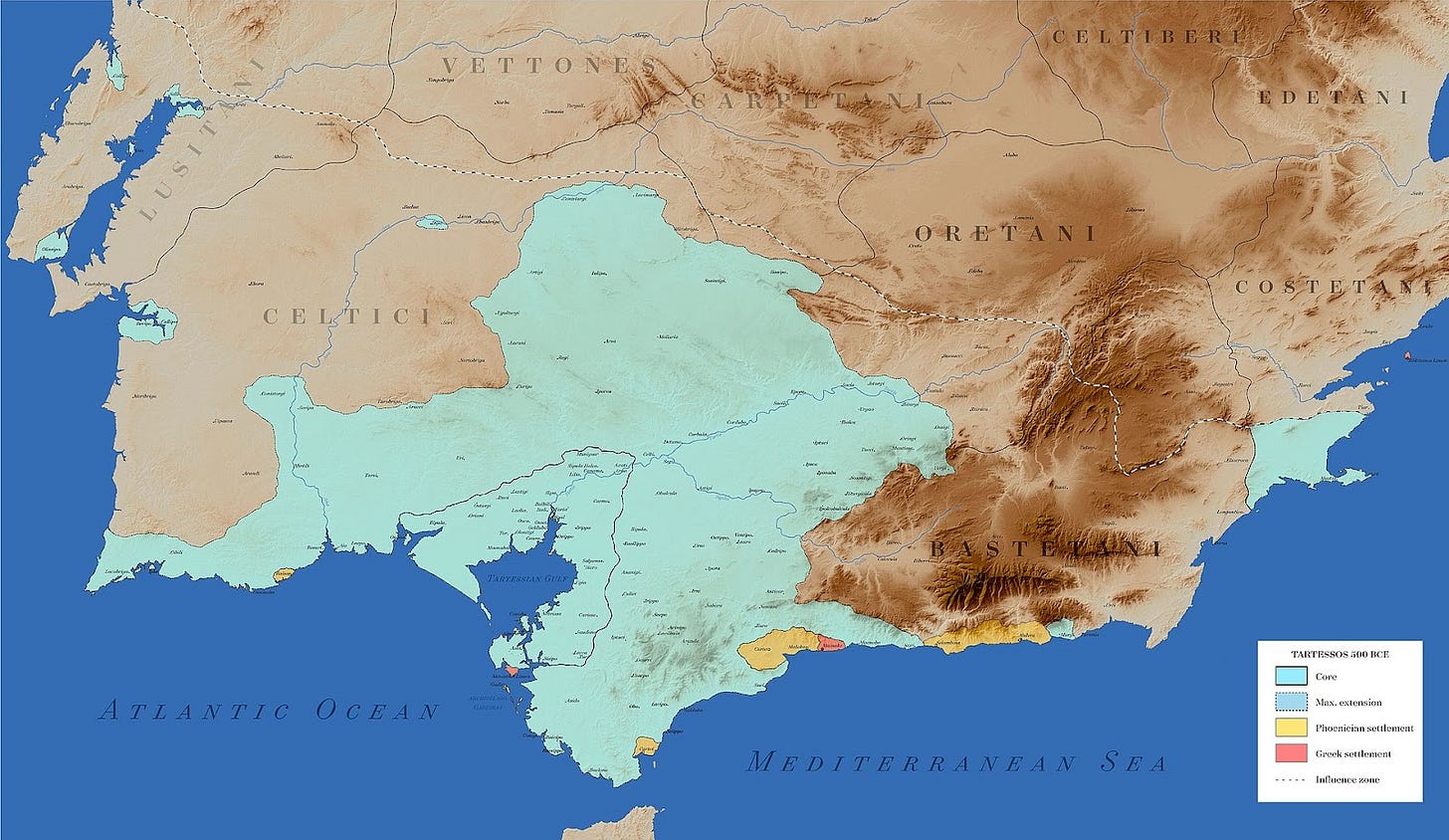

Based on isotope ratios of hacksilver hoards that match ores in the silver-producing regions of Sardinia and Spain, found in Israel dating between 1200 and 800 BCE, coinciding with the reigns of King Solomon (990-931 BCE, give or take based on sequential chronology) and Hiram of Tyre (980-947 BCE, again giving or taking a few years depending on chronology used), it is known that Phoenicia and Israel did have contact with both Sardinia and Spain. Differentiating between these two is quite burdensome due to their centrality in mining and the metals trade, with many of the Phoenician settlements making it difficult to understand the origin of the word ‘Tarshish’, with Phoenician being a closely etymologically linked language to Hebrew. Among them was the major port city, and capital of a kingdom of paleo-hispanics, named ‘Tartessos’. This city was located somewhere on the Tartessian Gulf in the Baetis River valley - also known as the Guadalquivir river valley in Andalucia, south Spain.

Large Version of the above image available here

Further complicating the uncertain location of Tarshish at Sardinia or Tartessos is the town located inside the Tartessian heartland called ‘Tharsis’, in Huelva. Unhelpfully this town is even a mining town dating back to the pre-phoencian era. If I were to weigh in without any evidence I would personally assume this founder named ‘Tarshish’, like Alexander, founded multiple cities in his name. All three of these locations would be exporters of metals, but only Sardinia would act as a port hub for west mediterranean metals trade. While Tartessos was a center of power and major exporter, it would only have been so for the incoming Atlantic trade through the pillar of Hercules - otherwise known as the Straits of Gibraltar. Regardless of if the actual Tarshish was located in Sardinia, all of the trade from Tartessos, Spain would have traveled through Sardinia, via the Phoenecians, on its way to Israel. This makes Sardinia the probable location for Tarshish, or at the very least some section of his descendants - who might also have traveled between Spain, or even Sicily and parts of North Africa.

Another fairly short section, but realistically it could probably be doubled in length due to the debate surrounding Tartessos vs Sardinia. I mostly excluded the Tarsus=Tarshish theory as well, since that comes from later Christian traditions with no rational basis, nor rooted in Jewish tradition. This section is a candidate for something I’d return to and write a part two that would randomly get tacked on; but it would still be a weekly update, just not released in ‘order’ like sections so far.

Thank you once again for reading, subbing, liking, and giving me your feedback. Let me know if you liked this weeks maps, since some of them I even found quite in depth and interesting. The location for Phoenician trade goods, relative to their regions, as well as the large map of Tartessos are some of the better maps I’ve personally viewed out of the thousands I’ve seen. This is obviously a niche subject, but offers a better look into not just Torah but also helps contextualize many real world locations, peoples, and events from history. In the words of Moshe Chaim Luzzatto :

“For there is no small or large thing in a general principle that does not have [some] application in the details. And if it does not add or take away anything about some of the details, it will certainly have great application about others. Since a principle is a principle about all the details, it must contain [some information] about each of them. Hence you must be very exacting about this and examine their functions, their relationships and their connections with great precision. And you must examine their processes and progression very very well - [to know] how one matter leads to another, from the beginning to the end. 'And then you will be successful and then you will understand.”

Reese, David S. (1987). "Palaikastro Shells and Bronze Age Purple-Dye Production in the Mediterranean Basin," Annual of the British School of Archaeology at Athens, 82, 201–206

Stieglitz, Robert R. (1994), "The Minoan Origin of Tyrian Purple," Biblical Archaeologist, 57, 46–54

Cazzella A, Moscoloni M (1998). "Coppa Nevigata: un insediamento fortificato dell'eta del Bronzo". In Troccoli LD (ed.). Scavi e ricerche archeologiche dell'Università di Roma La Sapienza. pp. 178–179. ISBN 9788882650155.

Pausanias. Hellados Periegesis [Description of Greece]. IX, 17, 5

Excellent detailed work. As expected.

interesting, getting into more name recognition of various lands, people, etc.