Our next list comes from Ramesses III around 1150 BCE from Medinet Habu where he lists the most complete grouping of seven peoples: Denyen, Peleset, Shekelesh, Sherden, Teresh, Tjekker, Weshesh. As mentioned, the Denyen are the primary seafaring group this time1, but the Teresh and Weshesh are also affiliated with the sea.2 Four of the seven groups are completely new, so let’s break into each one by one.

The first group are the Denyen whose appearance as prisoners from a relief at Medinet Habu on the second pylon shows their interesting headwear.3 We already briefly mentioned this group's connections on the Table through the Danaoi in Greek, to the Dodanim of Hebrew. This connection is extensively discussed in it’s own chapter on the Dodanim from the Book of Japheth, but the gist of the chapter is a theory positing a link between the corrupt chronicles version of the name “Do(r)danim” and the terms “Dor(ian)” and “Dan(naoi)”. This would be the Dor-Dan, with the attached suffix -im we know so well to imply ‘of the sea’, they become the Dor-Dan-im.

These people would obviously be both the Doric invaders of Greece around the turn of the bronze age, as well as the Danaoi/Danaans who share another link to the Odyssey through their contribution to the forces besieging Troy. It seems very obvious the Denyen were an element of these troops.

They also appear to have lived around Cilicia, being the basis for the important city named “Adana”. If a Hittite report is to be believed, there was a “Muksus” in Cilicia mentioned alongside a king of the Danunians.4 There are Luwian connections all over this region, and it becomes the primary basis for the later Neo-Hittite polities that form interesting right after the collapse. Alternative names for this group appear to be “Dananiyim” which fits closer to the Dodanim found in Hebrew and appears as a middle way between the Greek and Hebrew variants for the term.5

The theory posited by many is that the Danaoi that ended up in Egypt who were resettled by the Pharaoh in Canaan most likely became the Tribe of Dan from the Torah. This theory is based on an interpretation from the Song of Deborah where they are described as ‘remaining on their ships’ which would hint at these Danites being a people of the sea.

I would effectively assume the Denyan represented the “Dan” component of the Dordanim as we will see another group that fits with the Dorians better than the Denyan, and their probable founder Danaus. So many connections for these people could be brought up that entire books could be written just on this group, so we will be forced to move on to the Peleset without getting too slogged down in scholarship.

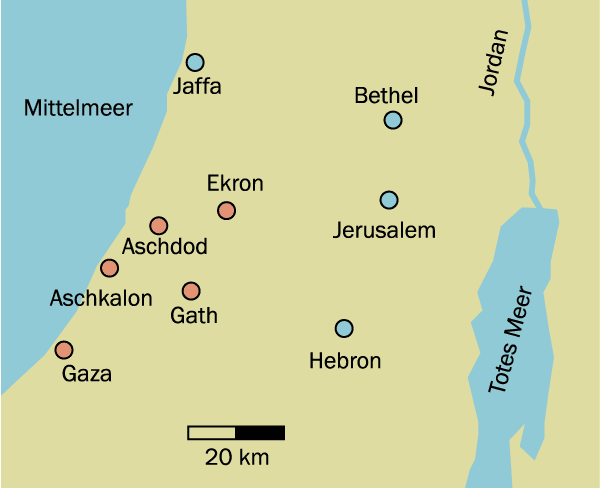

Peleset are one of the accepted identifications, with most historians and archeologists viewing them as related to the Philistines. The obvious “P-L-S-T” sequence is retained in Phi-Li-S-Tim which is important again because this term actually ends in that “-im” suffix implying ‘of the sea’ even for the Philistines. However, we know this group was based on land, meaning at some point the Philistines had to have been settled in the region which is what the bible hints at when describing their five cities alongside the “sixth” Avim, or giant, city. They clearly displaced this native Canaanite group, assimilating with them, and even the complicated stories of the Philistines descending from the Casluhim heavily imply their non-native background to help justify why their claim to the land is not valid.6

We have already dealt extensively with the Philistines in their own chapter, but we need to still connect this group with the original population since Peleset was an Egyptian categorization for foreigners. As mentioned previously, the term “Pelasgoi” contains “P-L-S-G” which seemingly doesn’t fit, but the D could have morphed into a G. These native inhabitants of Europe were forced into migration to the near east, being one of the larger populations bringing along women and children only deeper into the collapse period when they were forced to leave their homes. Those who left probably felt strongly about their identities, and their elaborate outfits probably reflected their desire to signal who they were during battle. Those “Peleset” that remained in their homeland assimilated into the cultures that took over, no longer deserving the ethnic designation of “Peleset”, or “Pelasgoi”.

The next group, Tjekker, are well documented in the Story of Wenamun as raiders during the reign of Ramesses III, additionally from earlier during Merneptah’s rule. Depicted during the Battle of Djahy we can see them alongside their allies the Peleset in their conflict with the Egyptians. The Peleset have the fan-like helmet, while the anchor-like symbol with a ball on top appears as the Tjekker.

This group is strongly associated with the port of Dor, in Canaan no less, where they probably developed this location from a small town to a large fortified city. Despite Dor being inside the territory of Manasseh, the tribe never successfully conquers the city from the residents of Dor, meaning their ethnic quality is most probably non-Israelite in character, like the Peleset. Based on both of these groups appearing together, it’s not farfetched to assume they were fairly near, and the city of Dor being flanked by Phoenicia and Philistia is a fairly good clue to their location on the coast, given their profession as seafarers.

Flinders Petrie actually believed this group's ethnonym was linked to the important city of Zakros in eastern Crete.7 This connection would provide a clue to the various Cretan, or Myceanean character of this group and they might represent the more “Cretan” variant, versus the later “Mycenaean” variant of people. In a strange twist, the classical Greek myth of Minos, king of Crete and namesake for the Minoans actually does have a connection to Sicily. Reportedly, in search of the legendary inventor craftsman Daedalus8 - known from the Labyrinth which housed the Minotaur, and the famed “Wings of Icarus” who burnt up after flying too close to the son - Minos voyages to Sicania, in Sicily. Whether the Sicanians had a “Minoan/Cretan” element to their culture is seemingly supported by this mythology, and might explain the other island people from Sicily as opposed to the Sicels who are more likely Shekelesh.

Another theory posits a connection between the Tjeker and the Teucri, or Teukroi, a tribe from northwest Anatolia not far from Troy.9 As mentioned before, there were probably two elements of “Trojan” society, and these Tjeker may have represented the Teucri component.

From Greek mythology we learn of the king of the Teucri and Troy known as Teucer who is actually related to Priam, Hector and Paris whom he fights against, alongside his brother Ajax, during the Trojan War. After he joins Phoenician King Belus of Tyre on his campaign against Cyprus, he is given the island as a reward for his loyalty, where he founds the city of Salamis, helping wrap in this far-flung Mediterranean dynasty that seemingly fell during the collapse.10

One interesting fact about Teucer is his association to the Hittite God Tarku, known as Teshub in the east who is an Indo-European storm god. This relationship to the Phoenician Belus begins to make more sense when one realizes Belus is affiliated with the Carthaginian storm god Baal Hammon.11 The extensive Greek and Phoenician colonization of the island that occurred at the collapse of the bronze age appears to be encoded once again into the mythologies of the ancient near east. The original inhabitants, probably partially Mycenaean, would probably explain the association of the Kittim, Achaens, Mycenaeans, and the original name for the island of Cyprus where in Greek it was called “Kition”.

Teucer importantly has a daughter named Batea who marries a man called Dardanus, namesake for the nearby Dardanelles. Dardanus inherits the Teucri kingdom - from Teucer, through Batea, after Teucer goes off to found Salamis - and becomes leader of the Dardanoi tribe. According to Herodotus there was a “remnant of the ancient Teucrians” that participated in a revolt against Persia in the early 5th century BCE, nearly 500 years later, when they were called by the name Gergithae. Later, Strabo provides an origin for the Teucri in Crete, in addition to claiming the Lukka came from there which might explain Minoan sites all over Lycia. All of this clearly implicates the Dordanim and shows a fusion of identities for a variety of people groups in the Dardanelles region to form a new identity during this period of cultural upheaval.

Finally arrive at the last group, the Weshesh, whose sequence reads W-Sh-Sh, and lack any known visual representation making them the most poorly understood sea peoples.12 They only appear during the 1150s, and at no other point is there an attack by Weshesh making it probable they are again affiliated with another group in different periods, under different role based tribal titles. Most probably they were a clan of Achaeans, similar to the Ekwesh.

Within Greek there is the settlement of Waksos located on Crete, connected to the tribe Waksioi.13 Some have also connected them to the Carian site of Wassos where extensive archeology reveals Mycenaean buildings, and two deeper layers of Minoan settlement.14 Thus, both sites connect to the Minoans, who likely represent the “Pre-Indo Europeans” the Greeks would have simply all called Pelasgoi.

Based on phonological similarities between the name Weshesh and the term Oscian - a neighboring Italic people to the Latins/Romans - these two people might be linked to the same original culture.15 These Oscans spoke a distinct language from the Latins, shared by their cousins the Umbrians, and together often called the Sabellic languages.

An alternative term for a group of Oscans were the Ausones.16 Quite strikingly, the Ausones are actually known from their legendary leader Liparus, who led the Ausones from the Aeolian Islands - off the coast of Sicily - between 1240-850 BCE lining up between this era.17 They appear to be “non-Greek” and later succeeded by the actual Greek Aeolians, according to Homer which again lines up with our immigrant displacement theories.

Tenuous, but still highly probable, is the connection between Oscans and the Anatolian state of Arzawa. Arzawa was a powerful state in western Anatolia that often intermingled in the political affairs of the Hittites, but appears more like a loose confederation of states, or peoples. Arzawa’s capital eventually became the site of Apasa, known today as Ephesus, one of the most important Greek centers in the classical period and member of the Ionian league.18 The name Ephesos is obviously similar to Wassos - Wassos is just south of Ephesos - and Waksos; Ephesos potentially represents the homeland of the Ekwesh, and Wassos land of the Weshesh.

To bridge this gap we need to return to the Weshesh as connected to the Achaens, and the Ekwesh. If this relation between the two holds, then it’s possible the Ekwesh represented the ‘northerly’ faction of this group, with the Weshesh representing the southern half, mostly in Anatolia. Both of them are collectively some Mycenaean civilization, and under Hititte terms would have been called Ahhiyawa. Ahhiyawa really only referred to the Anatolian coastal regions that were in constant conflict with the Hittites, but ultimately the cultural line between Mycenaean and Arzawan blurs in the Greek era becoming a single identity.

To be very clear, I do not actually think “Arzawa” and either the Ekwesh or Weshesh are the exact same groups, but their identity is important to unraveling this picture. Around the 1400s BCE there was a massive revolt against the Hittite Empire, termed the Assuwa Revolt for the name of the coalition that joined in open revolution. Egyptian sources called this league “A-Si-Ja” and in Mycenaean Linear B they were also called A-Si-Ja.19 Apparently, the Mycenaeans actually supported the revolt either militarily, or financially showing a close political affiliation between the two peoples. The Trojan War is almost certainly in part a reflection of this revolt, and many of the heroes were probably taken from these military conflicts.

According to Mycenaean sources the term Assuwa sounded like Asiwia, and was important enough to have been recalled into Greek becoming the modern term “Asia”, differentiating the cultural barrier between Indo-European Japhetite ‘Europe’ and Hamite ‘Africa’ and Shemite ‘Asia’. In the following Book of Shem, we will deal with the grandson of Noah named ‘Lud’ who probably represents the Anatolian Lydians whose kingdom centers around much of the territory we have discussed over the following chapters: Apasa/Ephesus, Arzawa, Assuwa, Luwia, Lycia, Caria, Troy, and centered on their capital Sardis.

Luwiya/Luwa, representing the Hittites term for the Luwians, is seemingly related to the Assuwa confederation and the state of Arzawa. Their emergence as a unified group following the Assuwa Revolt around 1400 BCE might have been one of the critical turning points in the Luwian ethnic formation, distinctly signifying them as one element of the Hittite empire that contested ‘Hittite’ rule of the territory.20 This may explain why later Neo-’Hittite’ states actually speak Luwian.

Members of the Arzawa coalition varied, but a partial list of the members will speak volumes: Karakisa, Lukka, Taruisa/Troy, Arzawa, Phrygia, Seha River Land (Sardis, Lydia, Lesbos) among a coalition of 22 other states. One other notable member we haven’t discussed is the Warsiya, with a name strangely reminiscent of the Oscians, and the Weshesh. The most probable outcome of the fusion of Mycenaean culture and Arzawan/Luwian culture was the production of an independent Indo-European ‘Weshesh’ group that eventually moved into Italy as the Oscans.

Now, there is one final theory, and that's who this group of Weshesh sea peoples show up as in the Hebrew records. Far from a fringe theory, many scholars have posited that the Weshesh immigrated into Canaan as the Tribe of Asher!21 Weshesh can be reconstructed as “Uashesh” since Weshesh is already a simplification for the English language, and in this form includes the name Asher more clearly.

The final list comes with no associated Pharaoh, probably because this is the one that resulted in the collapse of the dynasty. From the Onomasticon of Amenope, we are given the names Denyen, Lukka, Peleset, Sherden, and Tjekker. This time none of these groups are new, but it pays to return a second time to the Lukka to dig into a few final clues.

The confederation known as Assuwa that subsumed the regional identities of most of the discussed groups appears like the origin for many of the phases of localized collapse that eventually begins spreading around the near east. Connecting Assuwan militaries, mercenaries, events such as the Assuwan Revolt, the Trojan War, the Dorian ‘Invasion’ of Greece and wider Aegean colonization point to a series of events that force major chunks of the population to flea looking for a different life.

All of these groups appear to have some kind of Luwian connection, which aligns with our understanding of the Carians, Trojans, Sards, and Lycians as pseudo-Luwians. Western Anatolia was obviously known as “Luwia” separate from Greece, but assimilated into Greek culture during the Greek Dark Ages becoming known later as Phyrigia, known for their myths of Midas and his golden touch, the Gordian Knot cut by Alexander, and the myth of the Amazons. Eventually the entire western Anatolia is subsumed by the Lydians.

All of these immigrants from what we call the Sea Peoples were triggered by the revolts, forced migrations, famines/droughts, and natural disasters that were themselves downstream of the wider Indo-European dispersals from the Yamnaya steppe homeland north of the black sea. These competing pressures collapsing in on one another, fragmenting and decivilizing most of the known world into more simple components capable of withstanding the pressures. As hypothesized by Joseph Tainter, when a civilizations level of complexity outgrows the structural malleability of it’s bureaucratic requirements, hardening them into a rigid hierarchical class system with complex roles, dominated by inheritance based nepotism, then the inflexibility when faced with external challenges collapses the system in on itself due to an inability to reorganize labor responsibilities.

Breasted 1906, Vol IV, §129 / p.75: "of the sea"

Breasted 1906, Vol IV, §403 / p.201: "in their isles" and "of the sea"

Moreu, Carlos J. "THE SEA PEOPLES AND THE HISTORICAL BACKGROUND OF THE TROJAN WAR." Mediterranean Archaeology, vol. 16, Meditarch, 2003, pp. 114,

Burkert, Walter (1992). "The Orientalizing Revolution: Near Eastern Influence on Early Archaic Greece" (Cambridge:Harvard University Press) p 52.

The journal of Egyptian archaeology, Volumes 47–49. Egypt Exploration Fund, Egypt Exploration Society. 1961. p. 80

Aaron J. Brody; Roy J. King (2013). "Genetics and the Archaeology of Ancient Israel". Human Biology. 85 (6): 925.

James Baikie mentioned it on pp. 166, 187 of his book The Sea-Kings of Crete, 2nd edition (Adam and Charles Black, London, 1913).

Odd Daedalus retains the D-D sequence of Dodanim

The identification of Tjeker and Greek Teukroi, Latinized to Teucri, was first made by Lauth in 1867, and was repeated by François Chabas in his Études sur l’Antiquité Historique d’après les sources égyptiennes et les monuments réputés préhistoriques of 1872, according to the Woudhuizen dissertation.

Farnell "Greece and Babylon: A Comparative History of Greek, Anatolian and Mesopotamian Religion."

Heike Sternberg-el Hotabi: Der Kampf der Seevölker gegen Pharao Ramses III. Rahden 2012, S. 50.

ibid.

Mitchell, S.; McNicoll, A. W. (1978–1979). "Archaeology in Western and Southern Asia Minor 1971–78". Archaeological Reports (25): 59–90.

Heike Sternberg-el Hotabi: Der Kampf der Seevölker gegen Pharao Ramses III. Rahden 2012, S. 50

Diodorus Siculus V,7.

Hawkins, J. David (2009). "The Arzawa letters in recent perspective". British Museum Studies in Ancient Egypt and Sudan (14): 73–83.

Cline, Eric H. “Achilles in Anatolia: Myth, History, and the Assuwa Rebellion,” in Crossing Boundaries and Linking Horizons: Studies in Honor of Michael Astour on His 80th Birthday, Gordon D. Young, Mark W. Chavalas, and Richard E. Averbeck, eds. (Bethesda, MD: CDL Press, 1997), pp. 189–210.

Bryce, Trevor (2011). "The Late Bronze Age in the West and the Aegean". In Steadman, Sharon; McMahon, Gregory (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Anatolia. Oxford University Press.

N. K. Sandars, The Sea Peoples. Warriors of the ancient Mediterranean, 1250-1150 BC. Thames & Hudson, 1978