One of the most significant events in Egyptian history - rather world history, due to how the event shapes humanity's future - was the invasion of the eponymous “Sea Peoples”. Entire books and careers have been made of exploring the Sea Peoples origins, and the event has become one of the ‘hot topics’ of archeology due to its relationship to the “Bronze Age Collapse”. The Bronze Age collapse itself has become a flashpoint of debate, with its central transitional role in setting the stage for the Classical world.

Sometime around 1077 BCE, the near eastern world was rocked by a series of cataclysmic events with a range of causes theorized to be natural, cultural, political, or even triggered by a pandemic. None of these are fitting explanations, and instead a theory known as “Systems Collapse” pioneered by the work of Dr Joseph B Tainter is easily the best material on the subject of Systems Collapse Theory.1 Effectively, the theory posits that civilizational collapse is triggered by ‘social overcomplexity’ which results from a scaling resource demand forcing a reliance on systems that become increasingly unsustainable. One primary example of this is the available arable land for any given city, whereby the growth of a population can scale harder than the actual land can support with food, forcing them to outsource to supply their needs.

This happened to Rome during their Empire, whereby the city of Rome’s population exploded to the point Africa and Egypt supplied the primary grain for Rome. Eventually, those provinces began losing their effective grain output - in the case of Egypt decreasing reliance on seasonal flooding, and the drying of the North African coast destroyed Rome’s main food supply resulting in a collapse of the center of the empire outward. No longer able to support the needs of the city, revolts and social discourse begins to appear causing a breakdown in social cohesion. This ripples out to all corners of the globalized, connected world, such as the case of Rome, or during the Bronze Age when much of the known world was interconnected.

During the Bronze Age Collapse (BAC), a series of naturally triggered causes combined with an overcomplexity in social requirements, specifically in the highly organized and hierarchical top-down structure of the socio-political religious systems of the ancient world. The palace dominating the Mycenaean Greek world disintegrated, ushering in the Greek Dark Ages. The Hittite Empire, once the major dominant superpower on the map also vanished into a series of derivative city-states that only marginally claimed influence from the empire. Coastal cities across the entire Mediterranean were burnt to dust, with major cities like Ugarit, Troy, Akko, Qatna, Hama, Knossos, and even the cities of the Philistines being destroyed. Egypt and Assyria faced internal challenges, but still managed to survive in some form even if in a completely different state.

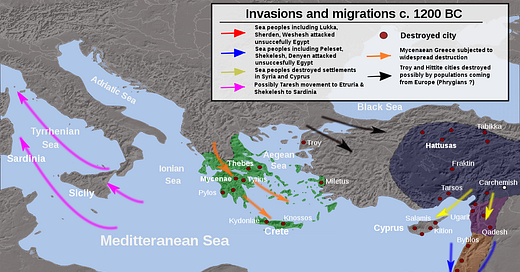

The BAC is so important precisely because of the confounding triggers, and the various causes that ultimately results in the mass migration and movement of peoples all around the ancient world. A sort of chain reaction occurred where people probably moved into one area, for example the Greek region, pushing the former Myceneans out into other regions, which itself triggered more resettlement, and further relocation. The following map really does the best job of summarizing the movements of the Sea Peoples during the BAC, even if slightly simplified.

This is truly a fascinating topic, but there is not enough time to fully flesh out everything. However, one major source of information of this period comes from numerous Egyptian reliefs telling of the Pharaonic battles with foreign invaders throughout this period. The name “Sea Peoples” is a bit of a catchy misnomer, as they were not much of a confederation, and over a nearly 150 year period varied in group composition showing a different narrative than a mass movement of peoples at a single time. Often, 50 years could pass between one sea peoples movement and anothers, with completely different outcomes such as military defeat, being hired into Pharaoh’s army as mercenaries, or even being forcibly resettled throughout Egypt.

Through this quite long era of sea peoples invasions there were a number of stela produced with different listings, from different Pharaohs. The first of these is none other than Ramesses II, The Great who on his Kadesh Inscriptions circa 1210 BCE lists Karkisha, Lukka, and Sherden.2 This first group, Karkisha, only appears here and is actually quite simple to well versed Hebrew grammarians who will know the word “Kashet קשת” which means ‘archers’.

In Anatolia, the region of “Karkiya”, or “Karkisa” is probably the origin for these people. They were not part of the Hittite empire, and had their own kids and authority, and were often employed as mercenaries by the Hittites.3 This term connects to the Greek word “Caria”, which is likely referring to the same region as Karkiya in Hittite records. These Carians and Karkiya were famed for their usage of the bow, hence their employment for their proficient skill, and explains the Hebrew terms similarity. The smoking gun for this is actually the next people listed, the Lukka, who are almost guaranteed the neighboring “Lycians” who are visible as neighbors to the Carians on the map.

Like the Carians/Karkisa, the Lycians/Lukka served as mercenaries at the Battle of Kadesh under the Hittites4, confirming their territorial neighbors to the Hittites. Centuries later, these Lukka turned against the Hittites and became a major problem for their kings, helping contribute to the collapse of the Hittites empire. It was probably during this period - given this first stela's inscription dates roughly near the Battle of Kadesh - that the Lukka began emigrating around the Mediterranean looking for better lives than one of constant military struggle.

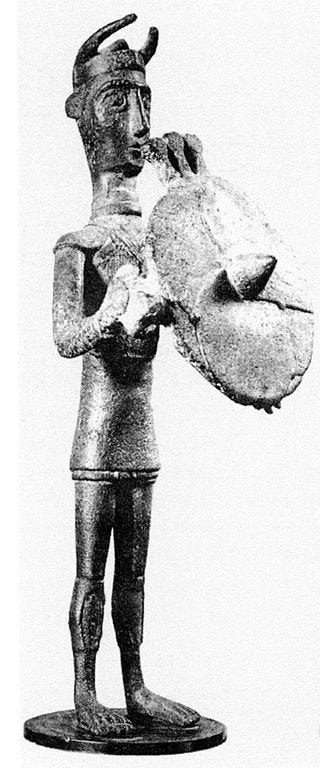

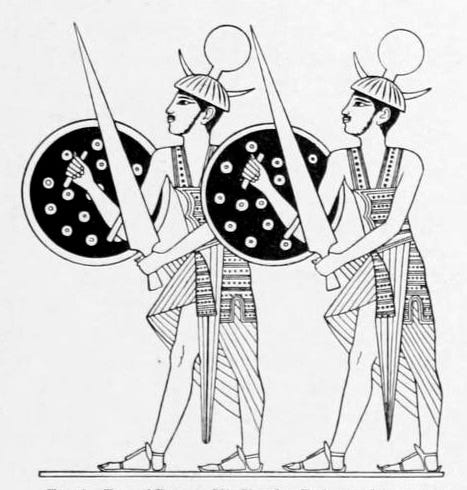

Alongside both these groups was the Sherden, who were again prized for their mercenary ability and often depicted in military contexts. Their prominent horned helmets are easily the most striking feature, but also that Naue II bronze swords5 which clearly indicate their preference for military roles within society. This outfit might give away their origin slightly since horned helmets are a fairly obscure and limited feature in the bronze age. As a result of their military prowess, many of the Sherdan are drafted into Pharaoh’s personal guard showing some trust for these seeming foreigners.6

In the Amarna letters they are probably known as “še-er-ta-an-nu”78 which phonetically is pronounced something like “She’erda’annu fitting with the Akkadian lengthening of these sounds. These Amarna letters come from an era before the Ramesses inscriptions, making it likely this was the earliest period of their activity in the ancient world and began establishing themselves centuries prior to the actual “Bronze Age Collapse.” From a later Ramesses III inscription it appears that he allows them to settle around Canaan in a territory that seemingly corresponds to the Israelite Tribe of Zebulun.

During this era their name became something more similar to “Sared”.9 The morphology of this name could imply their ethnonym was something like “S-R-D”, dropping the N from Sh-RDaN. This name suspiciously harkens to the “Sards” from Sardinia who share the same S-R-D ethnonym. This name is also notable in the toponym “Sardis”, a major city from Western Anatolia that exerted control over many coastal cities.

It is very possible the Sardinians migrated to Sardinia after having come from Sardis in Anatolia, or vice versa. For example, ancient Greek writers claimed Trojan refugees made their way to Sardinia becoming known as the tribe “Ilienses” who lived alongside the ‘more’ native Balares people. The Balares might be the “Nuragics” while the Ilienses might be the Mycenaean colonists who merge with the population forming a distinct identity.

They appear to settle in Northern Israel at the archeological site of El-Ahwat, contrasting with the Philistines who settled in the south. Dating of the site varies between 1150-105010, but either way fits in our range for the BAC and the Sea Peoples invasion. Interestingly, this location is the proposed site for the residence of Sisera, known from the Book of Judges 4-5 in his conflict with Barak. This would be his supposed capital, inside the territory of Zebulun, named Harosheth Haggoyim In accordance with the Book of Judges claim that Sisera had hundreds of chariots, there have been chariot lynch pins found at the site corroborating the evidence from the Torah.

The major feature of this site are actually the rounded huts, very different from the dwelling of other Canaanites making it suspect if this group has a relation to the island of Sardinia which features similar architecture called Nuraghe. The castle-like stone fortresses from the island of Sardinia are featured in the image, and show the uniqueness of such a design choice making it unlikely they are unrelated.

Additionally, there are bronze figures from Sardinia that feature the same swords, shields, and importantly horned helmets helping strengthen this theory. Cyprus also features similar idols with horned helmets, and is a known location for Nuragic settlements. Archeologists theorize that the Sherdana probably hopped over to Crete, then to Cyprus, making their way into the levant where they served roles in various administrations and military careers as mercenaries.11

There is a large dispute regarding “From the West” or “From the East” with regards to the Sherdana, but if they are the Nuragic people then it’s almost guaranteed they came from the west, in Sardinia, due to their centralize of cultural artifacts on that island, radiating out from it toward the east. The prevalence of their own language, and the known effect of population movement from the west to east direction rather than the opposite does seemingly imply they moved to the region as refugees of a sort. However, it is possible that the Sardinians and city of Sardis actually had a shared ethnogenesis elsewhere, and were at one time brothers who assimilated together on Sardinia.

From a Ramessid inscription “As for the Sherden of rebellious mind, whom none could ever fight against, who came bold-hearted, they sailed in, in warships from the midst of the Sea, those whom none could withstand; but he plundered them by the victories of his valiant arm, they being carried off to Egypt.” The text clearly states the Sherden were sailing in on warships from the sea, and were carried off, in other words captured, by the Egyptians.12 Interestingly the Sherden are the only group which appears on every single list, making them easily the most important element of this Sea People society, and their early listing might have been one of the first triggers in the movement of peoples around the region.

The first of these Sea Peoples: Karkisha (Carians), Lukka (Lycians) and Sherden (Sardinian Nuraghi) all serve as mercenaries, and appear to be fleeing less with entire families than in later eras when major population resettlements of these groups occur. These first groups really appear more like “adventurers” of a sort, looking for a better life, willing to perform tough but skillful roles in service of foreign kings. Perhaps these regions were unable to support the population sizes they had reached, and gradually waves of them began moving to other lands. As that effect begins, this ripples into other lands.

The next set of Sea Peoples comes from the reign of Merneptah where on his Great Karnak inscription he lists five groups: Ekwesh, Lukka, Shekelesh, Sherden, and Teresh. The Lukka and Sherden are repeats, and these two often appear on all, or most of the lists. What is interesting is the level of detail on this inscription seems to imply the Ekwesh, Sherden, and Sheklesh are “of the sea” - something similar to having the suffix “-im” in Hebrew attached.... - implying the Lukka and Teresh are not seafarers. However, a later inscription does include the Teresh “of the sea” making it confusing which groups are really ‘sea’ people.

Starting off with the Ekwesh, we can probably posit that like the “sea peoples” in the Table of Nations who all have the suffix -im, meaning “sea”, the sea peoples that are verified with this suffix in Egyptian would come from similar lands. The non-Mizraite children with this suffix are conveniently the Greek children of Javan, both Kittim and Dodanim. His other children, both Elishah and Tarshish, might be related to the sea, but not “island” people like those two groups. Interestingly, these two retain a “sh” sound similar to Sherden, Ekwesh, Shekelesh, Teresh. Whatever the exact connection, it’s etymologically obvious they are related groups.

Whether coincidental, or a work of God, the choice is yours, but the Ekwesh most probably line up with the Greek term “Achaea” which is the same as the Hittite term “Ahhiyawa”.13 In our Book on Japheth, the identification for the Achaea section of the four primary Greek groups was none-other than the Kittim who are one of the only groups retaining this ‘of the sea’ suffix in Hebrew. What is most striking is that like the Kittim who are primarily a “im” people unlike other Greeks who serve a dual “land people” role, the Ekwesh are exclusively called “of the sea” and the only other group to consistently be called “of the sea” are actually the Denyen.

Notably, the Denyen and Ekwesh never appear together on the list, seemingly as if they are elements of a unified people (Greek/Javan), and both from similar ‘isles’. This is slightly jumping the gun, since the Denyen come from Ramesses III around 1150 BCE, but the Denyen are almost certainly identified with the “Tanaju” from the Annals of Thutmosis III in reference to messengers from a Mycenaean king.14 The “Tanaju” or “Denyen” obviously retain the “Danaoi” of Classical Greece’s name, and it was in our Book of Japheth that again we identified the Dodanim with both the Danaoi, and as one of the primary groups that migrates around during the BAC. The retention of the -im suffix for the Dodanim is another strong clue, and this relationship between the Ekwesh-Denyen, Achaean-Danaoi, and Kittim-Dodanim pairs only becomes clear with a lengthy, but necessary, discussion of Greek mythology.

Tainter, Joseph (1976). The Collapse of Complex Societies (Cambridge University Press).

Bryce 2005, p. 336; Yakubovich 2010, p. 134

Bryce, Trevor (2005). The Trojans and their Neighbours. Taylor & Francis. pp. 143–144.

Bryce, Trevor (2005). The Trojans and their Neighbours. Taylor & Francis. pp. 82, 148–149.

Gardiner 1968: 196-197

Kitchen, Kenneth (1982). Pharaoh Triumphant: The life and times of Ramesses II, King of Egypt. Aris & Phillips. pp. 40–41.

EA 81, EA 122, EA 123 in Moran (1992) pp. 150-151, 201-202

Emanuel, Jeffrey P. (2013). "Sherden from the Sea: The arrival, integration, and acculturation of a Sea People". Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections. 5 (1): 14–27.

cf. Garbini, G., I Filistei, Rusconi, Milano, 1997: passim

Finkelstein, I. and Piasetzky, E. 2007. Radiocarbon Dating and Philistine Chronology with an Addendum on el-Ahwat. Ägypten und Levante: Internationale Zeitschrift für ägyptische archäologie und deren nachbargebeite Vol. 17

Karageorghis, Vassos (2011). "Handmade Burnished Ware in Cyprus and elsewhere in the Mediterranean". On cooking pots, drinking cups, loomweights and ethnicity in bronze age Cyprus and neighbouring regions: an international archaeological symposium held in Nicosia, November 6th-7th, 2010. A.G. Leventis Foundation. p. 90.

Kitchen, Kenneth A. (1996). Ramesside Inscriptions Translated and Annotated. Vol. II: Translations: Ramesses II, Royal Inscriptions. Cambridge: Wiley. p. 120 §73.

Kelder, Jorrit M. (2010). "The Egyptian Interest in Mycenaean Greece". Jaarbericht "Ex Oriente Lux" (JEOL). 42: 125–140.

Kelder 2010, pp. 125–126.

This is excellent. Well written, interesting and easy to read. Kol ha kovod!