As implied earlier in our discussion on Seba, this term must be related to Sab and the general region Sab was from, as well as his other brother Sabtah whose entire name is rooted inside Sabtecah. When discussing the etymology of Sabtah we gave two possible meanings: “to break”, but also variously “encirclement”; or some form of either of these terms. If we go with the earlier definition ‘to break’, Sabtecah would be almost a furthering of that term, possibly “breaking” or “striking”. This is an unlikely definition, and I do not personally find strength in the definition as breaking, or striking. I would prefer “encirclement”, or “to go around” from the term “Sabab”.

Turning our attention to the etymology of Sabtecah, it’s clear the term contains his brother's name “Sabte” as a prefix to the “cah”. Cah in Hebrew may be well known to most readers through names such as Michael, pronounced “Mi-Ka-El” traditionally. This name contains the shorter name “Micah” - well known from the name for the prophet - which removes the theophoric name “El”, one of the names for God. “Mi” translates to “Who” and “Ka” translates to “like”, collectively forming the name “Who is like God” in the case of Michael, or just “Who is like” when it comes to Micah.

If we are to go with this theory, “Sabte-cah” might be “Is Like Sabtah”, or possibly just a shortened form of “Who is like Sabtah”. The term is unlikely an official name for Sabtecah, and mostly meant to imply relation to Sabtah in some sense. Based on context in the Table of Nations, it could variously mean either region, or ethnic relation. Possibly, unlike all the other children, Sabtecah doesn’t represent a defined, separate ethnic group, but a continuation, or progression from an earlier “Sabtah” located somewhere near Kush, Butana, or Gezira. When the Torah uses roots, it rarely uses them isolated from other contextual clues that imply the roots direct meaning, and in this case the conjunction of “Who is like Sabtah” as well as a relative of the term “Sabab’ meaning “to go around” would both line up with each other.

Let us turn to one final ancient writer to help us certify the origin of Sabtah, and possibly Sabtecah. For the first time we will be looking at Roman engineer Vitruvius’s work “Ten Books On Architecture” where during a lengthy discussion of his river theory regarding the origin of most rivers “in the north” he relates the entire winding path of the Nile across Africa. As stated before, the ancient writers believed the Nile met the Niger somewhere around the Sudd, with the Niger being fed by the Atlas mountains. Ironically, we now know the Nile is one of the few, if not only major rivers that doesn’t actually flow North-South, but flows South-North. Vitruvius’s theory was mostly correct, but it’s ironic that the river being used in this description is incorrect, but still serves our purposes. Vitruvius states as follows:

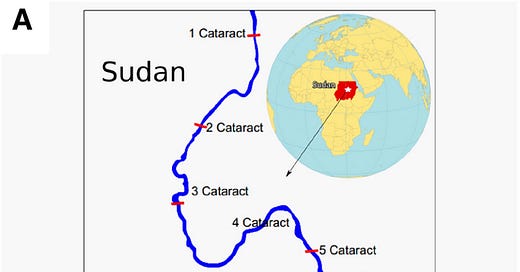

In Maurusia, which we call Mauritania, the river Dyris, from Mount Atlas, which, rising in a northern region, proceeds westward to the lake Heptabolus, where, changing its name, it is called the Niger, and thence from the lake Heptabolus, flowing under barren mountains, it passes in a southern direction, and falls into the marsh Coloe, which encircles Meroe, a kingdom of the southern Ethiopians. From this marsh turning round near the rivers Astasoba, Astabora, and many others, it passes through mountains to the Cataract, and falling down towards the north it passes between Elephantis and Syene and the Thebaic Fields in Egypt, where it receives the appellation of the Nile.1

We see a first hand example that ancient writers believed the Atlas river system met the Niger, and that the Niger met the Nile. What is unclear is the location of this “Lake Heptabolus” which could be identified as Lake Victoria, but is most likely Lake Chad which was far larger in this period, and was something closer to a super lake. For our purposes this isn’t important, as the Nile flows from the nearly proportionally sized Lake Victoria. At some point this river reached the “Marsh Coloe” which is obviously a reference to the Sudd. What is most interesting is that Vitruvius believes this marsh “encircles Meroe”, making it more likely the identification of the Gezira area near Khartoum, but might be a term to encapsulate the entirety of the region. Regardless, he states this marsh is near the river Astasoba, and Astabora, implying he viewed this “marsh” and the wetlands in the regions between the Atbarah and confluence of the Blue and White niles in the region of Butana. This is where Vitrivius places Meroe’s ethnic territory, and based on most ancient designations Meroe was significantly more southern than the previous Kushite periods even if they shared ethnicity.

As previously mentioned in our discussion of Meroe, the name “Meroe” was a later term, post dating the Persian King Cambyses and the original city was called Saba. While Greek and Roman writers tended to call the entire region “Meroe” after the capital, in reality it’s unlikely this was the primary name of the region or people, and simply a name for the capital island of Meroe. Since we haven’t deciphered much of the Meroitic language scholarship is still unsure what Meroe means, as well as many of the terms in the region including the other major cities of Naqa and Aborepi. It is most likely a foreign term, rather than an indigenous name for the area if the story about King Cambyses is believed to be true, and the original name was Saba. This would make sense why the people, and the Torah, would choose not to name them as “Meroe” despite it being a simple designation.

Meroe was indeed “like” both the Napatan Kushites, as well as Sab, making the name “Who is like Sab” line up with this identification. Beyond being “like Sab” Meroe also “went around” in a bend, “encircling” the region of Kush. Extremely creative scholars have even put forward that Sabtecah means “Encircle depression” which lines up perfectly with the “Island of Meroe” - variously known by the moniker “Butana plain” - even though these scholars didn’t associate Meroe with Sabtecah. Therefore we might conclude that the “Island of Meroe” is the location for our Sabtecah.

Furthermore we can see so far from all of the place names, and designations that the sounds contained in the names Sabtah and Sabtecah often appear in this area. “Na-qa” maintains the “a-ca” sound. Abore - from the city Aborepi - sounds similar to Astabora, which has the letter T and “Ah” sounds frequently in all of the related terms. Saba mirroring Sab(t)ah. Even cities like “Napata” contain the “ap” which would be pronounced closer to “ab” as well as the “ata” section of the term. Since we don’t understand Meroitic it’s very difficult knowing how, or if these terms relate, but there is clearly some linguistic similarity.

A final alternative theory is necessary for those unsatisfied with such a specific designation of Meroe, without any smoking guns that link Meroe to Sabtecah like previous children. I myself find it possible to group both Napatan Kush with Meroe, owing to Meroe’s 3rd century origin well after the completion of the biblical narrative.

Going off this Hebrew root of “Sabab”, which is as strong a piece of linguistic evidence as any, “to go around” and “encircling” from these terms may imply these people “were around the Nile”. It could be trying to clue us into the groups that don’t dwell on the Nile directly, but were related to the Cushites in some form. The most obvious of these people would be the Blemmyes who are archaeologically related to the C-group culture circa 1000 BCE. They are often also identified with the much later X-Group culture, more contiguous with the Meroitics. Identification for the Blemmyes as modern Beja people is generally accepted.2

Links between the Beja and the linguistically related Afar and Saho further south have been drawn due to all three groups living in the same area, and those people do represent a distinct subgroup inside the Ethiopian region. However, it is possible all of these Nomadic groups were considered a single entity in Egyptian periods referred to by the moniker “Medjay”.

These Medjay are generally agreed to be associated with the Pan-Grave Culture of Nubia.3 Most of these sites date between 1800-1550 BCE from Lower Nubia and Upper Egypt.4 Like the Nubians whose land was referred to as “Ta-Seti” in Egyptian - meaning “land of the bow” - the Medjay were also strongly viewed as fearsome bow warriors from the same “Ta-Seti” land. In later periods - likely owing to their frequent hiring as Egyptian mercenaries - the Medjay become an elite paramilitary force, almost like Rangers or Green Berets.5 By the time of the 20th dynasty around the 12th century BCE this term disappeared from Egyptian usage, implying it was never a proper name for the people.

Helping certify their identification with the Beja, or Blemmyes, are linguistic similarities implying Medjay spoke a form of Cushitic like the Beja.6 Quoting expert Claude Rilly “The Blemmyan language is so close to modern Beja that it is probably nothing else than an early dialect of the same language. In this case, the Blemmyes can be regarded as a particular tribe of the Medjay.”

Tentatively we could identify Medjay and the Beja as Sabtecah, or “People who are like Sab”, or who “Encircle” the Nile. I personally might prefer this identification as it aligns better with a separate ethnic group instead of doubling up “Nubians”, but it’s not impossible for two vastly different Nubian cultures to be listed alongside each other. However, the strange placement of Raamah between them almost is a hint that they are “not related” in some sense, even if the “name” relates them together, and makes it more likely that Sabtecah is identified in relation to Sab.

We could even argue Sabtecah are those previously mentioned Kordofanian languages further “encircling” the south Nile. This opens another pandora’s box as the previously discussed “cross African Nile” theory of the classical world implies a people “who are like Sabtah” could always be located much further down the Nile. These “encircling” people could very well be the West Africans around the Niger Bend, or one of the non-Dedanite groups in the region. This may explain why Sabtecah is placed after Raamah and Dedan in the list.

We have three possible identifications: “Island of Meroe” and its people, Medjay/Blemmyes/Beja/’Others’, and “down Nile” populations past the Sudd along the Niger River fitting some group discussed during Dedan. A reader is free to choose any of these options given the absence of strong evidence, but identification ‘in absentia’ is often on shaky ground, and nothing but conjecture. If I were forced to provide a location, I would downplay the likely-hood of the Medjay, but open up the “Medjay” to include a cross Sahelian population, possibly even towards Sao, including many of the Oasis peoples, and trans-Saharan trader populations. If we were to do this, it would incorporate most of the “Proto West African” pastoralists around the Sahel, and leave “Dedan” to imply a more specifically “Nok” culture along the Niger, rather than the Sao-ites at Lake Chad, or the Tichitt Manda that found Ghana and Mali. We could always group Nok with Sao, and then say Tichitt is variously Dedan or Sabtecah, but the specific organization of these groups is not all that important without better archeological records.

While these identifications may not satisfy readers, ultimately there is no way the Table of Nations would have listed all the various African groups. In effect, by saying “those who go around” with the implication of meaning “the groups surrounding the Nile”, the bible successfully wraps all of the remaining African groups into one category.

Next up is Nimrod. No way to prepare a reader for his nightmare. I have actually written an entire 2nd book with 230 pages of content on Nimrod, entirely separate from the earlier book on Japheth and the coming book on Ham. This book serves as an insertion for ‘Nimrod’ on the table, but could just as easily be read stand alone as it fully tells the story of figures unrelated to the Table of Nations.

As a result, it will be some time before we return to Ham and his child Mizraim (Egypt), but if a reader is intensely interested the entire book is prepared already so I will be publishing that book shortly. See you then, and thank you for reading.

Jitse H.F. Dijkstra (2013), "Blemmyes", The Encyclopedia of Ancient History, Wiley, pp. 1145–1146.

Näser, Claudia (2012). "Nomads at the Nile: Towards an Archaeology of Interaction". In Barnard, Hans; Duistermaat, Kim (eds.). The History of the Peoples of the Eastern Desert. UCLA Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press. pp. 81–89.

Wilkinson (2005), p. 147

Rilly, Claude (2019). "Languages of Ancient Nubia". Handbook of Ancient Nubia.