Riphath

Identifying the Riphaean Mountains and the associated designation for descendants of Riphath

Riphath, Gomer’s second son, is most clearly etymologically linked to the Riphaean mountains which are classically identified with either the Urals, placed north of where Gomer would likely have lived, or possibly the Carpathians in Dacia near modern Romania, southwest of Ashkenaz. Theories for the mountain have been debated since antiquity, with ancient writers placing them often in the Urals but also showing strong associations to the Carpathians.1

In classical Greek sources the Riphaean mountains were the location of a mysterious ‘one-eyed’ people called “Arimaspi” from northern Scythia, living at the foothills of the mountain range. Helping locate these people are tales of their battles with gold-guarding griffins in the far extreme northern lands of Siberia, called “Hyperborea” in Greek sources, near the cave of Boreas, God of the North Wind. While the original source was written by Aristeas and communicated to us through Herodotus, the work is now lost making it difficult to trace this lead any further. However, if the story is to be believed this certainly places them in the extreme north, near the Urals, rather than Carpathians.

Obvious is the name “ca(rpath)ian” which contains most of the necessary sounds to form the name “Riphath”, but based on most ancient writers and their associations with the extreme north around the Volga river implies the Carpathians were a later designation, possibly due to the Riphatheans moving to the region. Interestingly the eastern Carpathians were called the “Montes Sarmati” in Latin sources, implying Sarmatians - a sub tribe of Scythians - were living around the region in later periods. The western Carpathians were potentially related to the tribe of the area named “Carpi” but it is likely that these people were given the name for the mountain they lived around similar to Riphath, and Riphatheans. It is unclear which ethnic group the Carpi belonged to, and likely contained Dacian, Sarmatian, Germanic, and Celtic components.

Looking at ancient writers' proposed links to these people, according to Plutarch the Celtic peoples passed through the Riphean Mountains enroute to Northern Europe.2 If this is true, that link is a strong connection for the biblical Riphath as progenitor of the Celts. The established close ties between Celts and Germans with often overlapping and assimilating groups would identify Celts close to Ashkenaz both physically and on the Table of Nations. There is also no traditional association for the Celts on the table, and for such a major group - even more major than the Germans - to be excluded from the list would seem strange. If the Celts were on the list, it seems this may be the most likely identification through process of elimination (spoilers, they aren’t any of the other children on the table).

Hippolytus of Rome proposed that Riphath was the ancestor of the Sauromatians, a group he viewed as distinct from the Sarmatians who were descendants of Ashkenaz - at least in the view of Hippolytus. While these groups both did live quite close to the Urals and Carpathians in multiple periods; a close look at this theory begins to crumble when one realizes the Sauromatians and Sarmatians are not actually different people but an earlier, and later phase of the same group. Owing to Hippolytus’s later date of writing around the 2nd century AD it makes it unlikely any of these people were still in the region during his time of writing, and it would have been some 500 years since the Celts were in the area. The fact Sauro/Sar-matians both do not have any connection to the Celts, and even have historical confrontations between the groups, helps confirm that Hippolytus wasn’t exactly correct.

Flavius Josephus supposed that the “Riphatheans, [were] now called Paphlagonians”, a group of people living in the very north of Anatolia. These were some of the more ancient groups on record, well pre-dating the Bronze Age collapse and comprising major military allies of the Trojans during the Trojan War around roughly 1200 BCE. These Paphlagonians were likely related to the earlier Kashka people, but relation between these groups is uncertain and may represent a foreign element that mixed into the native Kashka. Some scholars believe that the Kaskians were similar to the Hattians, but unlike the Hattians who were subsumed and assimilated into the Hittite identity, the Kaskians retained their identity in the north.3

The Kashka themselves were not native, and according to Hittite records circa 1450 BCE the first appearance of the Kashka is from this era after they moved into the region from the Propontis - a term for the inland Sea of Marmara that connects the Aegean Sea to the Black Sea. An earlier people in the region were the “Pala”, which may be the origin for the term “Paphla” which sounds an awful lot like Pala mixed with Riphath. Did these terms fuse after the Riphatheans moved into the region? Were the Paphalagonians possibly some sub-group of Riphatheans?

The Pala - as opposed to the Paphalagonians and Kashkans - were not Hittite and based on the phonology of their language, Luwian innovations suggest a previously shared Luwian-Pala linguistic complex.4 Luwian, Pala, Hititte and Lydian represent the four major branches of the now extinct “Anatolian” language family showing most of these groups were unified at one point, or another including the Kashka. All of these Anatolian people never coming across the “Riphean” mountains helps affirm they are not the identification for descendants of Riphath, but that doesn’t rule out the later Paphalagonians who might actually be pseudo-Celtic.

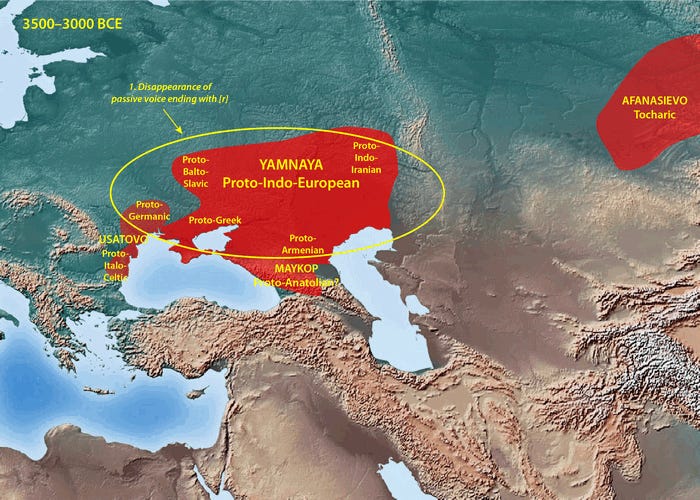

What is critical is that the actual Yamnaya homeland would extend almost exactly from the Urals to the Carpathians. While elements closer to the Urals were more “Indo-Iranian” than Celtic, it’s very possible the proto-Celtic people had moved from those mountains, or splintered off from the wider Indo-Iranians as they crossed over the Riphaean range, forming their ethnic identity, and lending their name to the Carpathian mountains.

In the attached map, between 3500-3000 BCE the Italo-Celts represent the closest group to the Carpathians, helping provide a tentative geographic link for all these theories. The reality is that the term “Celt” is actually a much later term attested to in the earliest Greek sources as “Keltoi”. According to Herodotus these Celts were located around the origin of the Danube river near the Alps circa 500 BCE.5 Archaeological sources help correlate Herodotus’s claims showing that the core of the Celtic territory was north of the Alps near the primary Celtic cultural sites of Hallstatt and La Tene visible on the other attached map.

These sites all arose out of the earlier Urnfield culture, itself a splintering of the Bell Beakers. The Bell Beakers represent the major genetic component for Western European R1b Haplogroup in modern Europeans as opposed to the Corded Ware of North-Central Europe who are mostly R1a. The Bell Beaker originated in the year 2800 BCE, roughly around the period migrations out of the Yamnaya homeland would have begun moving west. It is likely in some period between 3000 BCE and 1200 BCE when the earliest evidence of Celtic culture proper forms that both the early Bell Beaker proto-Italo-Celtic groups and the Corded Ware Proto-Germanic groups all migrated from Yamnaya. The split between “Bell Beaker Celtic” and “Corded Ware Germanic” is the dividing line between the two halves of Europe.

What is still unclear is where the Italic group would be categorized within this framework due to the possible “Italo-Celtic” language family implying a close connection between these two groups. However, like the Proto-Germanic group they may all be brothers, or uncles and nephews which would just as easily explain something as fluid as language families. Hypothetically, Riphath is not “Celtic” but rather Proto-Celtic, representing the period in time that both Celtics and Italics were unified. “Celt” and “Italos” would be two sons of Riphath. Indeed Greek and Roman mythology believed there was a semi-mythical figure named “Italus” who was King of the Oenotrians - an ancient Italic people in the south of the peninsula. In one telling of the myth, Italus was said to be a grandson of Odysseus known well from the Odyssey and Iliad. Sadly this Italus was a later figure from the Iron Age, rather than the Bronze Age when the Italo-Celts were closely related.

Also from the Roman Iron Age was the region of “Galatia” whose name comes from the Roman terms for the Celts, “Gaul” or “Gallia”. Three tribes of Gauls moved into Galatia, located in central Anatolia coincidentally just south of the territory settled by the Paphlagonians, around the 2nd century BCE; making it much to late for an identification of Riphath, but it does show that the Gauls/Celts felt some reason migrating into Anatolia was viable, perhaps due to tales of past Celts doing the same feats during eras of the Paphalagonian invasions. These groups had all crossed over to Anatolia from the Balkans after moving there from the Danube where the rest of the Celtic groups were located.6 On the attached map the Celtic regions of settlement are depicted.

Crucial to understanding the Celtic culture is that Celts were almost similar to Jews in the way “Celtic” was not an ethnic designation but a cultural appellation. Celt was a term meant to refer to the religion, cultural, and artistic traditions of these people which are all learnable traits that could have been adopted by “Non-Ethnic Celts” from other regions. This process of “Celtization” began as early as the 4th century BCE specifically in Pannonia where La Tene sites can be found.7 Among these tribes were the Pannoni and Dalmatae who respectively lend their name to Pannonia8 - roughly contiguous with modern Hungary - and Dalmatia9 - the coastal region of Croatia where the “Dalmatian” dog breed is known to have originated. The latter Dalmatae are considered closely linked to Albanian through multiple geographic toponyms that share names with the Dalmatae. While the Dalmatae were “Celtized” the Albanians were never Celtized, and retained their original identity and language.

The reality is that many Illyrian groups in general adopted “Celtic” traditions, making it difficult to identify them through archeological remains alone. Illyrian chiefs and kings are often buried with bronze torcs around their necks which is a notable Celtic burial practice.10 This same practice of Celtization occurred for the Dacians and Thracians, who originally had their own independent languages with starkly different traditions despite all being Indo-European groups. This process additionally occurred with Germans and Italics oftentimes blending many of these groups together. Germanic groups such as the Veneti - from where the term “Venice” comes from due to the region they settled around Venice - were Celtized by the 4th century BCE and according to writers like Polybius their languages were “nearly indistinguishable”.11

Among the Celtized Germanic groups that entered Italy were the major Celtic tribe “Boii” whose name likely originates from Indo-European. Disputed is the exact root of the term as the word variously could mean “Cow” or “Warrior”. Again through Polybius we are told in the very first historical reference to the Boii:

“They lived in unwalled villages, without any superfluous furniture; for as they slept on beds of leaves and fed on meat and were exclusively occupied with war and agriculture, their lives were very simple, and they had no knowledge whatever of any art or science. Their possessions consisted of cattle and gold, because these were the only things they could carry about with them everywhere according to circumstances and shift where they chose. They treated comradeship as of the greatest importance, those among them being the most feared and most powerful who were thought to have the largest number of attendants and associates.”

Clearly these Boii were noted agriculturalists, but also their reliance on a strong warrior culture. This same link to cattle herding has been made between the Cimmerians and the Gomerians. Upon examining Sanskrit, it is evident that the term for a cow is 'go', which also holds true in proto-Germanic. It is plausible that the name Gomer was derived from a word related to cattle, similar to how the Celtic word for cows gave rise to the name Boii. As many Indo-European societies were heavily involved in animal husbandry, it can be inferred that they held cattle in high esteem.

Like most migratory herding populations these Boii were all over the place, but their original location may have been the valleys of Boiohaemum which is actually the root of the term Bohemia where the Boii were located. Boiohaemum itself is a mixture of the term Boii and “Haimaz” meaning ‘Home’ in German. Other derivations of this root for cattle were the Illyrian tribe Boioi, as well as the Greek tribe of the notably important Boeotians who were themselves known in Greece as a people of cattle. Another tribe called “Baiovarii” obviously stem from this root, with this group specifically becoming the origin for the term “Bayern” which is the German word for Bavaria. Even the term “Italy”, shared by their Celtic brothers Italics from their ancestor Italus is likely a term that means “land of calves” further reinforcing this theory that the Boii, as well as the Celts and Italics, were intense cattle herders.

Finally, and potentially most importantly, is the term “Boiorix” for “King of the Boii”. Rather than a King of the Boii, this Boiorix was actually a chieftain of the Cimbri which shows how the term was used for more than the specific “Boii” tribe native to Bohemia. There is debate regarding these Cimbri and the language they spoke; variously Germanic, Celtic or even Cimmerian - the latter Cimmerian showing the close link between Gomer and his Celtic/Germanic children. Modern populations such as the Welsh and the Italian Zimbar people claim descent from the Cimbri, but it is unclear if either of them are related to the original population.

Another prominent mixed Celtic-Germanic tribe were the related Sicambri. Like their neighbors the Cimbri, the Sicambri lived within the “Nordwestblock” where modern Netherlands is believed to have formed it’s ethnogenesis. Tribes such the Batavians - seen as the progenitors of the Dutch - the Belgae - obviously the root of the country Belgium - the Salian Franks, and of course the Sicambri all of which whom join the Frankish Confederation that goes on to unite much of Western Europe and found the nation of France. This region is seen as the area where Germanic and Celtic cultures fused, and even today the separation between “French” and “German” cultures is often centered around Belgium as the dividing line.

One important feature of “Celtic” identity was the usage of Celtic languages found in the roots of territories they settled and the names of their members. Some of the most notable languages still in usage are Welsh and Irish (Gaelic), as well as Scottish Gaelic, Manx, Breton and the barely living Cornish. Dead languages included Pictish spoken by the Picts of Scotland, Brittonic which was the original language of “Britain”, Celtiberian spoken in Iberia which is now known as Spain and Portugal, Gaulish spoken in France, Noric, spoken in Austria, Galatian previously mentioned to have been spoken in Anatolia, and finally Lepontic spoken in the Alps. Collectively these languages comprise nearly the entirety of modern “Western Europe” and arguably form the core traditional cultural difference between the West and East, where “Hellenization” spread Greek culture, rather than Celtic. Oftentimes there is an erroneous view that “Latinization” was the defining traditions of Western Europe, or even Europe broadly, but this is not the case as Latinization was a process occurring through the entire mediterranean, including Greece, Egypt, and North Africa. “Latin” culture is a much later identity arising from a fusion of those Greek and Italo-Celtic elements.

Looking at a linguistic chart of the Indo-European languages shows many disputed links for the Italo-Celtic branch and how it fits into the wider picture. Many argue Italic fits better into either Graeco-Armenian or with Germanic. What is clear is that Germanic is quite close to Italic and Celtic in some capacity. Whether or not Italic fits into Albanian-Germanic, or with Celtic isn’t exactly important since the Albanian-Germanic branch certainly split off from Celtic, with or without Italic separately splitting. It is therefore clear that the “Italo-Celtic” and “Alban-Germanic” form some sort of closely related group as would be evidenced by the Dalmatae or Veneti.

Also clear is that the Graeco-Armenian, Indo-Iranian, and Balt-Slavic families split off from a common ancestor shared by the Alban-Germanic and Itao-Celtic branches. All of these branches were at one time shared with the Tocarian and Anatolian groups.

The Balto-Slavic group is a much later post-classical group that splits from the Indo-Iranian group, possibly related to the Sarmatians due to a high proportion of their remains matching Slavic genetics. This group would therefore not be early enough to constitute its own grouping on the Table of Nations - most likely being grouped into an “Iranian” group - but all the other groups with the possible exception of Tocharian would have had major identities in the Bronze Age.

Over the coming chapters these are many of the groups we will be looking for since they fall under “Proto-Indo-European” and all represent some unit of Yamnaya migrations. Germanics were obviously identified with the Ashkenaz, and the Italo-Celts would slot nicely into the position of Riphath. Both of these groups are divisions of the broader “Scythian”, or Yamnaya steppe groups. Future groups that split off from Yamnaya include Indo-Iranians who may potentially be two or more groups, the extinct Anatolian groups of Luwian, Hittites, Lydian, and Pala, and the Graeco-Armenian branch which may also be split into its own “children”.

The Graeco-Armenian branch is hotly contested, with Armenian often debated to be even grouped with other Indo-European languages, and oftentimes Greek itself splitting off from the Balkan branch which includes Albanian and the other related Illyrian languages. Included in this group is Messapic - a south italian language - and the important “Thraco-Illyrian” group as well as the Geto-Dacian group that potentially falls into Thraco-Illyrian. Most of these groups are now extinct making it extremely difficult to trace their origins based on language alone and requires putting all the puzzle pieces together in order to unravel the picture which is exactly what we will do over the coming sections.

A final curious problem for the term “Riphath” is that later Chronicles 1:6 refers to Riphath with a Dalet, instead of a Resh, with the name “Diphath”. Presumably this could be some sort of later scribal error, but at this time it remains to be seen if there is a view that can synthesize Riphath-Diphath as some sort of linguistic shift over centuries. This theory needs further exploration, but we cannot explore it any deeper.

What is clear after this dive into the Celts is their shared identity at times with the Germans; both of these groups themselves sharing traits from the Cimmerians. Based on these familial associations it's obvious that Celts and Germans are brothers, and potentially descendants of the earlier Scytho-Cimmerian proto-culture. This would firmly place them as the brothers Ashkenaz and Riphath, sons of Gomer who himself was previously identified with the Cimmerians. Additionally we can group the “Italic” branch of the wider “Italo-Celtic” language family as also descending from Riphath. Rather than viewing the Celts as Riphath, we should view both the Celtic and Italic cultures as derivations of the earlier Riphathic “Italo-Celtic” culture.

Once again thank you for reading this weeks post and I sincerely hope you could gain value from reading. If there is any crucial take-away from this post it is the association between Riphath and the Italo-Celts, making these groups the likely designation for Riphath’s associated tribes. The subject matter can be quiet dense and challenging, so don’t be afraid to leave a comment and ask me anything additional to help round out a piece of the puzzle.

Also feel free to leave an ideas for additional posts, or subject material. I’d be glad to break up the weekly Table of Nations writing for either another subject inside Torah and Tanach, or even broader Talmudic and Judaic studies. I’d even love to write something on a political subject, or how some of these historical ideas connect to the modern world, but I will leave that for brainstorming.

S. Casson, "The Hyperboreans" The Classical Review 34.1/2 (February - March 1920:1–3)

Keil and Delitzsch Biblical Commentary on the Old Testament: Genesis 10:3.

Singer, I. Who were the Kaska? // Phasis. Greek and Roman Studies, 10(I), Tbilisi State University, 2007. — P. 166—181.

The Indo-European Language Family: A Phylogenetic Perspective, p. 7. N.p., Cambridge University Press, 2022.

Herodotus, The Histories, 2.33; 4.49

Periplus of Scylax (18-19)

Mocsy, A.; Frere, S. Pannonia and Upper Moesia. A History of the middle Danube provinces of the Roman Empire. p. 27 and 55.

Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Antony (2003). The Oxford Classical Dictionary. p. 1106.

Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Antony (2003). The Oxford Classical Dictionary. p. 426.

Wilkes, J. J. (1992). The Illyrians. p. 233. ISBN 0-631-19807-5. Illyrian chiefs wore heavy bronze torques

Scullard, H.H. (2002). History of the Roman World: 753 to 146 BC. p. 16.