The Meroitic empire’s waning years were sometime around the year 350 AD, following the collapse of Rome, where they were reportedly destroyed by the Aksumite empire.1 Attesting to this is a Geez stele - the language of the Aksumites not spoken at Meroe - found in Meroe, showing that the Aksumites did extend their power all the way into Nubia. In Greek, a bilingual language of the region, the stele reads this unnamed ruler was “King of the Aksumites and the Omerites” around the year 330 AD.2 While Aksum’s identification is plainly clear, the less obvious designation is that of the “Omerites”.

Helping us identify the Omerites is another Greek inscription at Axum, where we get a lengthy description of this possible revolt at Meroe, translated as follows:

Aeizanas, King of the Axomites, and the Homerites, and the Rhaeidan, and the Aethiopians, and the Sabaites, and of the Silee, and the Tiamo, and the Bougaites, and the Kaens, King of Kings, Son of the Invincible Mars at a time when the nation of the Bougaites had rebelled, (I) sent our brother Saiazana and the Adephai (governor of a district) to subdue them by war!3

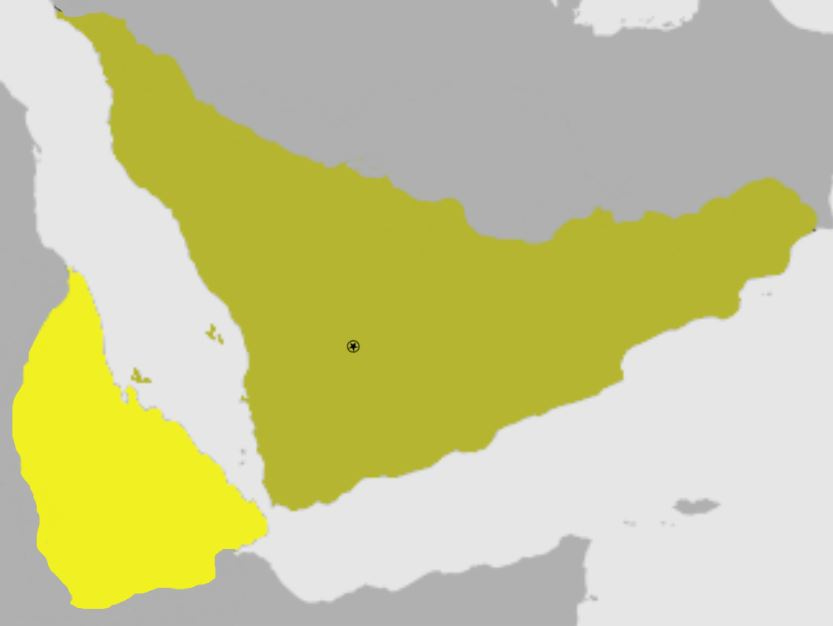

This inscription gives us a few clues to the way the natives referred to the region, and surrounding peoples. First we can see the “Omerites” are actually the “Homerites” or the “Himyarites” which were an extremely powerful Kingdom controlling most of Arabia from their seat of power in Yemen. The next reference is less clear, but obviously has links to the Himyarite dynasty of “dhu Raydan”. The Himyarites, unlike the Sabaeans, never control any parts of Africa and only retain parts of Yemen. The earliest reference to “Raidana” is possibly in a book published all the way back in 1786 at Harderwick called “Historia Imperii Vetutissimi Joctanidarum in Arabia Felice” which could be translated as “The Imperial History of the Ancient Joktanites in Arabia Felix” extracted from the works of a Greek poet named “Amriolkerius” who chronicles regions of the Indian ocean on a voyage to India and Ceylon.4

Further helping certify the location of Raydan somewhere in Yemen is the capital of the Himyarites called “Zafar”. Zafar may be a later name for the city as the central area of the Himyarite fortress is located in an area of Zafar called “Husn Raydan”. Reportedly in the older periods the Kingdom may have been called simply “Raydan” before conquering the other surrounding regions.5 Interestingly, the city, as well as much of Himyar, had a sizable population of Jews and Christians, being some of the earliest places to adopt the Abrahamic faiths helping show they were well connected with the Israelite political world and an inclusion of relative groups on the Table of Nations would not be strange.

The reference to Aethiopians at first obvious, is actually more interesting than it appears. Why would the Aksumites mention the Aethiopians as a separate people then themselves? The obvious indication is that they were indeed separate people, and the Aksumites proper were a more coastal, Eritrean people, north of the Tekeze river contrasting to the highland “Ethiopians”. This gives us evidence for there being separate ethnic designations within this language family, which is critical since it isn’t exactly the later Aksumite Kingdom that could be identified in the Table of Nations, but rather, the ethnic people that will go on to form that Kingdom, descended from a son on the Table of Nations.

The next obvious group on the list are the Sabaites, but again it’s not exactly clear who these “Sabaites” are in this period, and the list doesn’t necessarily give any clues in its ordering. However based on the identification of Himyar, it’s likely these are the “Yemeni Sabaeans”, showing Aksum, centered in Cush rather than Arabia, was at some point the “Center of Sabaean power”.

Following the Sabaites are the “Silee” who appear like a new group, but based on etymological reasoning are most likely a reference to Zeila, discussed at length in the chapter on Havilah, in this period.

Tiamo is a clear allusion to the western Arabian coastal region known as “Tihamah”.

Less clear are the “Bougaites” but based on etymology and a soft pronunciation of the “g” as a “j” this becomes an obvious reference to the Beja people.

“Kaens” is unclear but might be a royal moniker like the Nubian/Meroitic title of “Kandake” which was a Queen. Kaens might thus be a term to refer to a King, coming before “King of Kings” might make sense. Or it could be a people group, but it doesn’t appear critical to the text. Fundamentally from this text we can see all the regions controlled by the Sabaean Kingdom centered around Yemen are also controlled by the “Aksum” - or potentially also “Sabaean” - Kingdom pictured in the following image.

Most striking about this text is Ezana being described as “Son of the Invincible Mars” which sounds more like a Roman Emperor’s epithets than anything found on a supposedly Christian King’s sites. Helping explain this may be that Ezana in this period had yet to convert to Christianity, since it does appear he was the first Aksumite to start conversion in the region enmasse. Ethiopian traditions do claim Ezana was the first, and that Christianity first appeared in the 4th century AD, so this goes a long way to certifying the reign of Ezana.

One final interesting line is the usage of the term “Adephai” to refer to a governor of a province of some sorts. This term may be related to the Jewish term “Adonai” which essentially means “Lord”, and would have been used similarly to “Baal”, meaning Master in Canaanite. A seemingly unimportant line helping us indicated a large semitic intermixing of the Aksumites in this period, and their cultural contacts to the near east, attesting to an extremely likely inclusion of these people in the Table of Nations. The question next becomes who were they in that period, as the Aksumite empire is a much later phenomenon.

This will be answered next time, where we will identify Raamah and the etymological grounds that support him being the founder of the broader ‘Ethiopian’ peoples.

Dows Dunham, Notes on the History of Kush 850 B. C.-A. D. 350, American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 50, No. 3 (July – September , 1946), pp. 378–388

Fisher, Greg (27 November 2019). Rome, Persia, and Arabia: Shaping the Middle East from Pompey to Muhammad. Routledge. p. 137

Valpy, Abraham John; Barker, Edmund Henry (28 February 2013). The Classical Journal. Cambridge University Press. p. 86.

Jérémie Schiettecatte. Himyar. Roger S. Bagnall; Kai Brodersen; Craige B. Champion; Andrew Erskine; Sabine R. Huebner. The Encyclopedia of Ancient History, John Wiley & Sons, 2017