Unlike all the other sons of Ham, Put is the only one who has no children. While one may think this means Put had no children, it actually serves as proof that the Table of Nations is not attempting to fully list every single tribe, or people, but rather unified groupings based on various linguistic, ethnic, and cultural similarities. We can confirm this reality from the comments of Rabbi Obadja Sforno, 15th century italian Rabbi, who in his commentary on Genesis 10:6:1 says: “ופוט וכנען, the sons of Put are not mentioned separately, as they all formed a single nation retaining the name of their founding father. Proof of this is found in Ezekiel 38,5 “פרס, כוש, ופוט אתם”, i.e. even in the days of the pre-messianic wars of Gog and Magog, Put will still have its original name.” We can see from Rabbi Sforno that at times nations did have multiple tribes, but the Torah felt it unnecessary to list everyone, or it would be attempting a genealogical chart, which is not the goal of the Table of Nations.

Due to his lack of listed generations, this actually makes Put slightly less certain to identify as there is nowhere to corroborate who, or what should be “in the land of Put”. The most important thing to note first is that Put was actually pronounced “Phut” or “פּוּט” in Hebrew. This makes the erroneous identification with Put as “Punt” quite clear1, since the “F” sound is lacking in Punt, and the “N” is lacking in Phut. Phut and Punt are these separate locations, which squares away with the fact Phut was often allied to Mediterranean nations, and not Arabian nations, making it more likely north and along the Mediterranean coast.

In agreement with this are most classical scholars, and Rabbis, who place Put in Libya, to the west of Egypt. According to Josephus, the native inhabitants of Libya were called “Phoutes”, however he goes on to specify that there was a river “in the country of moors” which additionally bore the name Phoute.2 Pliny3 and Ptolemy4 also identify a river “Phuth” in the west of Mauretania, placing it in modern Morocco (West Mauretania is effectively Morocco and East is effectively Algeria).

Along with nearly every single biblical reference to Put they are mentioned as warriors, likely mercenaries, of Egypt and Persia. Ezekiel 27:105, 30:56, 38:57, Jeremiah 46:98, and finally Nahum 3:99. All of these references put ‘Put’ near Egypt and Cush - notably no Arabian or East African nations are mentioned - and nearly every time Put is mentioned along side “Lud”, or “Lubim”. Not only does this show Put is definitely west of Egypt and Cush, but also helps certify Lud and Lehabim, the sons of Mizraim, as also coming from the north west.

Additionally inside Egyptian records there is a Libyan tribe named “pidw” from records of the 22nd dynasty. This being a later 9th century reference doesn’t exactly place Put as originating in Libya, but certainly shows a strong connection. The later Pharaohs of the Greek Ptolemaic dynasty also refer to a “land of the Pitu” in reference to Libya.

In Babylon we even have references to Libya as “Puta” and Nebuchadnezzar II claims to have defeated “Putuiaaman”, an obvious portmanteau of “Putu” and “Iaaman”, or the Babylonian name for Greek. This “Iaaman” or “Javan” is likely because by the 5th century when Babylon arrived, Libya was heavily colonized by Greeks and effectively became “Cyrenaica”. Finally, in Persian records, while clearly from the 4th century and later, the satrapy - a province - of Libya was named “Pataya”.

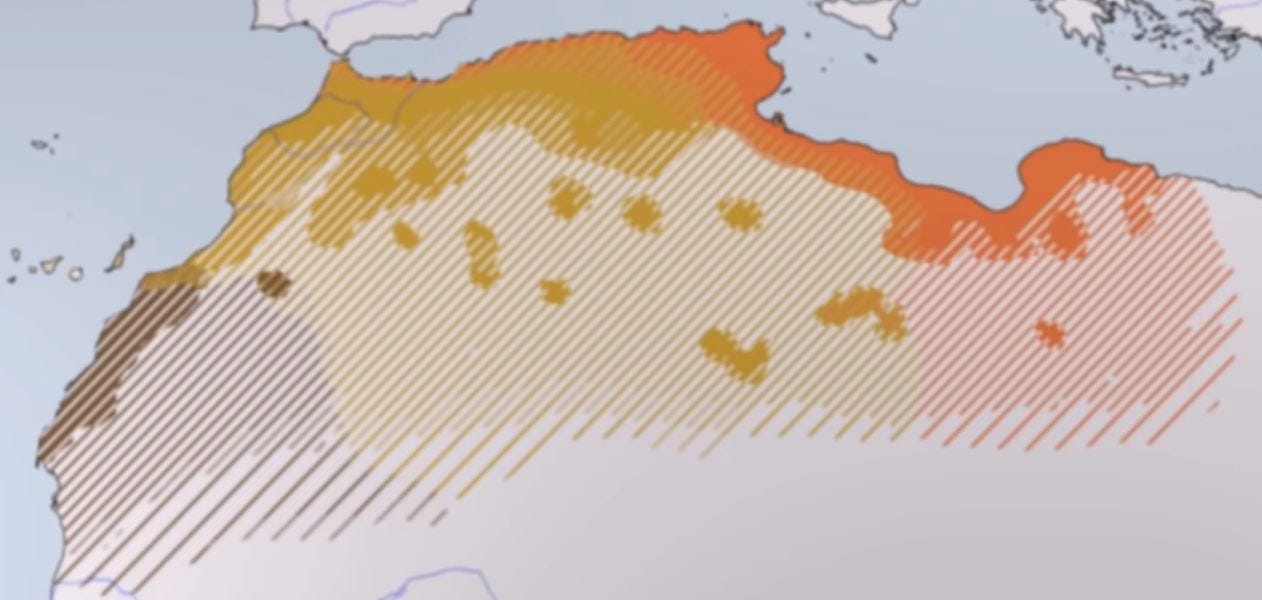

While there is no specific tribal designation for the group in Libya, and we don’t know “who” these people are, their designation as also having a river named after them in Mauretania suggests these are the same people as modern Berbers, who inhabit the entire region of Africa between the Mediterranean and the Sahel - the term for arable west africa. Any readers educated in ‘Berber’ history are aware that this term is actually pejorative, and stems from the Greek Cyrenes10 who called these people “Barbaroi”, the same designation as “Barbarian”. In the way calling a modern British, or German person a “Barbarian” is offensive, it would similarly be offensive to call them anything other than the indigenous endonym for the people ‘Amazigh’.

The Amazigh have inhabited Tamazgha, the native name for Mauritania11, for over 5000 years, and evidence of Amazigh languages first show up around the year 3000 BCE near Libya. While many would assume this “Libya” is Cyrenaica - the main population center of the region by the time of Rome - there were actually three Libyas in this time period. While the main Libya would be Cyrenaica, or “Libya Superior” as it was known in Roman sources, modern day “west” Libya would have been called Tripolitania in this period. While there are no native names for Western Libya, it's likely that similar to Put being used to refer to the entire “Libya” region, corresponding to the Egyptian term “LBW” or “Libu”. While the “Li” part of the term fails to transfer over to Hebrew, the “Bu” part is clear. However, this is not necessarily the only designation of Libya in Egyptian records.

The Egyptians also used the term to refer to “Libya Inferior” or what was called “Marmarica” located in modern western, coastal egypt. In ancient and classical times, this region was considered Libya proper, and not part of Egypt, or Mizraim, which was centered around the Nile. Complicating this further is the fact that modern western Libya around the Gulf of Sidra would have been called “Syrtis Major” or Greater Syrtis, with the region even further west in the Gulf of Gabes being called “Syrtis Minor”, or Lesser Syrtis.While the naming of these regions is complicated, until 500 BCE the entire region was settled by Amazigh, speaking a variety of languages, but all under one family.

Eventually these languages split into a western Amazigh, and Eastern Amazigh, with the western branch being spoken in Mauritania. The eastern branch, or “Old Libyan” would have been spoken in all of these areas. Many of the Oasis across Africa would have been Amazigh for thousands of years until the arrival of Arabs. However, around 1200 BCE at the end of the Bronze Age the actual population of Tamazgha was a bit more complex, and it’s unclear if Libu were the same as the Amazigh, or if that remained true for the western egyptian oasis peoples, many of which even in native Amazigh languages speak different sub-dialects that can be quite different. While Cyrenaica - or Libya Superior - was Amazigh in this period, the territory to the east is less certain to have any Amazigh until the Bronze Age, and this region is consistently called “Libu” in Egyptian sources. It is important to stress that each of these Oasis would have their own “identity” and likely not be grouped within Meshwesh, or Libu.

During the 18th dynasty of Egypt, in the Late Bronze Age, the name given to the Amazigh in this region is “Meshwesh”. Note that Meshwesh is not a place or region, but a people as indicated by the terms “Meshwesh of Libu”, and later Meshwesh being in different locations. At first this name is quite odd, but the root of “Mesh” is the same as the “Maz” in Amazigh. This root for the Amazigh is found all throughout the different foreign names for the people, with various tribes such as: Massylii, Masaesylii, Mazyes12, Maxyes13, as well as Mazices and Mazax in Latin sources. Interestingly by the 22nd dynasty we get a “Meshwesh” series of Pharaohs, the Shoshenqs and Osorkons - the double “sh” sound being retained in Shoshenq’s name.

During the same period as Shoshenq we find figures such as the High Priest of Ptah named Pediese who is called a “Chief of Ma”14, clearly a reference to the various “Ma” tribes of the A(ma)zigh. These Pharaonic “Chiefs of Ma” are known to be Libyan Meshwesh. The original Shoshenq is actually Shoshenq A, another “Great Chief of Ma”. His wife was named “Mehtenweshkhet A” showing a retention of that “Wesh” sound. His father was actually a man named “Paihuty”, eerily similar to the Hebrew term “Put” and many of the names for the region found in other languages.

Based on the records from these Pharaohs; it does appear that the Meshwesh dynasty has a connection to Libu, as they are explicitly stated to be descendants of “Buyuwawa the Libyan”, but this line making them descended from Libu is unclear if specifically the Pharaoh himself was descended from them, or if the entire people were from the Libu. Interestingly the term “Buyu” seems like a cognate of “Libu”, and if you put them together it forms “Libuyu” sounding an awful lot like Libya. Either way, it’s obvious in Egyptian times the native inhabitants of the western region separated the Meshwesh and Libu, as well as a Buyuwawa and possibly others Amazigh.

Interestingly we find that following the campaign of Ramesses against the Meshwesh, as often done after ancient battles, the Meshwesh are settled around various cities inside Egypt with the goal of “hearing the language of the Egyptian people” and making their language disappear”. While we see the Meshwesh lived in Libya, they actually lived all over Egypt with various tribal chieftains spread throughout the delta. Importantly the Meshwesh were foreigners, and would not be grouped inside “Mizraim” as they are never assimilated, in contrast to the native inhabitants of the oasis.

Pushing this theory to its brink let us bring in one final piece of evidence that was reported by Flinders Petrie as coming from Herodotus. Herodotus claims there was a group of warriors named the Automoli in Greek sources, or Asmach in Egyptian sources, that had come from ancient Egypt. These people inhabit the same region as the ancient Macrobians, who according to Herodotus were the “tallest and most beautiful on earth” as a result of their primarily meat and milk diet. At first these parables are strange, but “As-moli” forms the modern term Somali, and the Somalis are tall, dark warriors with a legacy in sea trade, and a diet rich in animal protein such as meat and milk.15

For Flinders Petrie’s piece he connects these Automoli, or Somali, with the Meshwesh, possibly settled in the region by the Pharaohs; as we have seen Egypt often settles people in foreign lands to erase their heritage. While this Meshwesh connection seems strange, it starts to line up with ethnic place names in Somalia. Arguably their most central and important city in Somalia all the way until the 20th century was the city of “Berbera”, obviously named so due to these “Meshwesh Berbers” who were similar to those inhabiting the Libyan coasts. In Arabic sources this area was later called the “Land of the Barbars” indicating an Amazigh presence in the region well into the Arabic era, and a lack of integration with Egyptian identity, or religion.

Even more impressive is the city “Barbar” on the Nile, located in Sudan.16 It is quite obvious that the Amazigh, and the Meshwesh, got around, which fits with their nomadic lifestyle through the centuries. What this does is help provide a possible explanation why in the New Kingdom period the term for the region of the resettled Meshwesh on the coast of the red sea is “The Land of Punt”. Does this name connect to the Land of Put? Where did Egypt get this term from in the first place? Are there any native archeological records calling Punt, Punt? More mysteries for later archeologists to uncover.

For our purposes, we have successfully identified Put with not just “Libya” as is traditionally known, but specifically with the native Amazigh of the region, and their descendants. However, the complex ethnic identity of the Amazigh shifting over time makes it unclear how, or what groups compose the Amazigh in this period, and which later groups end up contributing to the Amazigh ethnic pool.

Groups such as the Garamantes of the Fezzan Oasis who by 1000 BCE had their own language and their own sub identities, and could likely constitute their own people, or sons of Put. Placed alongside the Garamantes would be groups like the Mauri, who lend their name to the well known “Moors” that take over Spain. The Numidians who controlled major Kingdoms in the roman era around modern Algeria, and large parts of Tunisia. Others like the Gaetuli deeper in the Sahara, inhabiting the desert regions south of the Atlas mountains. Even a group sharing their ancestors name, the “Fula” people distributed all over West Africa. Each of these groups could have theoretically been a son of Put, but in that period were entirely nomadic, tribal ethnicities, and thus were excluded from the Table of Nations.

This was a fun one for me to write, with some very original ideas that you can’t find in any scholarship, or literature. Hopefully this really helps you understand what “Put” means in the context of all those biblical references, especially when they take part in the armies of Persia, and Gog e Magog.

Next time we will begin the final son of Ham, Canaan, who has some fairly easy, but extremely interesting identifications for his children.

Sadler, Jr., Rodney (2009). "Put". In Katharine Sakenfeld (ed.). The New Interpreter's Dictionary of the Bible. Vol. 4. Nashville: Abingdon Press. pp. 691–92.

Nat. Hist. 5.1

Geog. iv.1.3

Persia, Lud, and Put were in your army, your warriors; shield and helmet they hung in you, they provided your beauty.

Cush and Put, Lud and all who support her, and Kub and the people of the allied land will fall with them by the sword.

Persia, Cush, and Put are with them; all of them with buckler and helmet.

Ascend, you horses, and rush madly you chariots, and let the mighty men come forth, Cush and Put, the shield bearers, and the Ludim who grasp and bend the bow.

Cush was [its] strength, and Egypt, which had no end; Put and the Lubim were your helpers.

Cyrenaica, Libya

This is a Roman term named after the “Mauri” tribe of Morocco, which is the origin of the term ‘Moor’.

Hecataeus of Miletus

Herodotus

Kenneth Anderson Kitchen, The Third Intermediate Period in Egypt, 1100-650 B.C., Aris & Phillips 1986, §§81f., 155, 301

Journal of the East Africa and Uganda Natural History Society, Issues 24-30. The Society. 1926. p. 103.