Going off the location of Lehabim as the central knife nome of Egypt, we can more easily place Naphtuhim as bordering his brother’s territory. While normally we wouldn’t know exactly where a territory is in relation to one another, being “generally near” another is as close as we could come, when it comes to Egypt, especially Upper Egypt, there is only one direction to go: south. Since direction and geographic location is not critical to a brother, instead we will go North East, to Canaan, where we will look for Hebrew roots in the Torah similar to Naphtuhim.

In the original Hebrew the term is “נַפְתֻּחִים” which is a plural, including the ending suffix “-im” as we’ve discussed. We can cut that ending off as it refers to the “Naphtuch” people of Egypt in this first reference from genesis. Interestingly, that is the only time this term is ever used in this form. We get a similar word to Naphtuhim in the form of “נֶפְתּוֹחַ” or “Naphtuach” which refers to an opening, and may be the actual root meaning of the term Naphtuhim. Another potential form is “אֲנָפָה” which only includes the “Naph” portion and means a Heron, or general unclean bird. Another term is “נָפַח” which refers to “breath”, but in context the term normally means “to breath life”, or to even take away life. There is even a son of Asher named “Harnepher” which is clearly Egyptian in origin, and as we know from Greco-Israelite names, or the extensive use of German names among European Jews that there is nothing fundamentally strange about a name of Egyptian origin found in a tribe of Asher. The typical assumption that “Jews must have Jewish names” is a modern viewpoint scholars hold due to their inability to grasp Judaism’s innovative cultural diversity that enabled it to incorporate any cultural substrate.

We get a reference in Jeremiah 2:16 with the line “Also the children of Noph and Tahpanhes will break your crown.” Tahpanhes is certainly the city of Daphne in the north, while Noph could be a city founded by Naphtuhim. The line used here is “Bnei Noph” meaning children of Noph, so it’s possible they are descendants of the Naphtuhim but not Naphtuhim proper. This may be unlikely based on references found elsewhere, for example in Hosea 9:6 the line “Moph shall bury them” is strangely similar to the term “Noph”. While normally I wouldn’t assume these terms are similar, and there is certainly no scribal error present, these terms in ancient Egyptian were actually linked. Both Noph and Moph are probably from the term “Men-Nefru”, Egyptian for Memphis. Due to Memphis’s notable burial grounds, it’s clear in the case of Hosea it’s obviously not in reference to Naphtuhim. It might be possible that all references to Noph are irrelevant to the Naphtuhim, and meant as identifications of Memphis.

Further in Jeremiah chapter 44:1 Noph is again brought up “The word that came to Jeremiah concerning all the Jews dwelling in the land of Egypt, those dwelling in Migdol and in Tahpanhes and in Noph and in the land of Pathros, saying:” This line directly refers to the Jews dwelling in the land of Egypt, noting what could only be presumed to be major Jewish settlements of Migdol, Tahpanhes, and Noph - helping attest to their relevance in a Jewish context since Jewish readers would have known these cities due to the Jewish inhabitants and their ties to Israel. Additionally, the end of the line uses the term “Eretz Pathros” meaning “Land of Pathros”, explicitly calling pathros a land, unlike the other three terms referring to cities. This will be important in our next section dealing with Pathros as it affirms in this case Pathros, or the Pathrusim, have their own land while the “Noph” are merely a city, and unlikely to be a reference, or even related to the Naphtuhim.

Again reaffirming this is another reference to Noph as the “princes of Noph” in Isaiah 19:13 - this time implying a sort of “royal dynasty of Noph” which is affirmation of Pharaonic dynasty practice on the city level. Yet again in Ezekiel 30:14 alongside Pathros, Zoan, and No, Noph is mentioned as the “Noph adversaries [who] will attack [Egypt/No] daily”. During our discussion of Ludim we mentioned Zoan was a city in the north - possibly Tanis - and was a “plain” that likely was a fertile agricultural ground explaining the many references to “setting fire to Zoan”. No is most likely a reference to the capital of the South, Thebes, called “Niwt” in Egyptian. For now this reference will be set aside, but it appears here that Noph are actually causing some sort of domestic dispute within Egypt, and attacking other cities, and people in the land. This is quite odd, but we will temporarily shelve this idea and return to it later in our discussion of Naphtuhim.

Finally, and most interesting of all these is the term “מִצְנֶפֶת” or “Mitznefet” a clear portmanteau of “Mitz” from Mitzraim and “Nefet”, possibly the real origin of Naphtu. The priestly mitre, in other words a turban was termed in Hebrew מִצְנֶפֶת Mitznefet and was the head covering worn by the High Priest of Israel when he served in the Tabernacle and the Temple in Jerusalem.

In order to find a potential link for this “Nefet” term is Egyptian let us turn to the Brooklyn Papyrus, a medical text from the year 450 BCE describing the treatment of snakebites. In this text we find usage of the term “hafaw nefet” referred to a snake that is “quail colored” and makes a loud blowing noise. Hafaw is the term for colored, as in “hefaw arar” or “sand colored”, and in this case Nefet would refer to a quail, or a clear call back to a specific “unclean bird”. The “blowing noise” that this snake makes might be a clear reference to the “breath” that takes away life. The fact Hebrew and Egyptian appear to agree on both these alternative roots implies the term isn’t inherently Hebrew, and is - rightfully so - Egyptian.

With this meaning of “breath” implying the giver of life, and the imagery of an unclean bird, we can continue our search for this cultural milieu not longer than after the Middle Kingdom and the Lehabim. Obviously the question should next be “Which gods or goddesses were associated with unclean birds, or even specifically Herons, and had the ability to take away/give life?

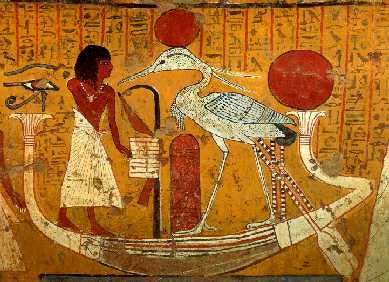

One of the more important, but lesser known deities in Egyptian religion is the bird god “Bennu”, or “Bn.t”. As with the Mnevis and Apis bulls, the Crocodiles of Crocodilopolis, or the well known worship of Cats across Egypt; the Bennu bird was often worshiped as the living embodiment of the gods. In this case, Bennu was often a stand-in for Ra - and by extension also with Atum - being called the “Ba” of Ra which is an Egyptian term referring to the “personality quality of the soul”.1 Bennu was said to have flown over the waters of Nun that existed prior to creation, helping determine the nature of creation itself showing Bennu’s centrality in the Egyptian religious pantheon.

Bennu imagery often puts one atop the pyramid caps called “Benben” stones, helping attest to the importance of this figure in the era of pyramids. In his role as creator and renewer of life, Bennu was titled the “Lord of Jubilees” and associated with the Heb-Sed festival where Pharaoh’s would reassert their power after specific periods of rule. In a broader sense we could view this association as being the general overseer of the “transfer” of Egyptian Pharaonic power from one generation to the next, rather than having a specific association to any period, or Pharaoh propping up his worship and cult center.

When affiliated with Ra, Bennu was linked with the Sun, and therefore creation. In this role as a “creator”, Bennu was often associated with the cycle of birth and death, and specifically the concept of “rebirth”. In this early period of Egyptian worship during the Old Kingdom when Ra and Atum were at their height, Bennu took the form of a small song bird. Evidence for this can be found in a limestone relief wall fragment from the sun temple of the Vth dynasty, during the Old Kingdom, which shows traces of blue-gray paint pointing to something closer to a Kingfisher bird called “Hn.t” in Egypt matching closely with the term “Bn.t”.

In a seemingly mythological parallel the Kingfisher bird would fly lowly over the surfaces of watery bodies, loudly shrieking making the legendary claims of the Bennu. A parallel to the cult of the Nile Goose associated with Amun in later periods, which was also imagined to be honking loudly in the primeval dark above the calm waters before bringing forth creation with its noise. All of this most probably feeds into the later Greek myth of the Phoenix, and its cycle of rebirth and death.2

While this imagery is not a Heron, it is indeed an “unclean bird” with not just this specific songbird but all songbirds being unkosher birds. However this association of Bennu is merely the Old Kingdom period, and by the New Kingdom artwork clearly shifts to depicting Bennu as none other than a massive gray heron perfectly matching our etymology of “unclean Heron”. There may be a real world match for this Heron as the Ardea Bennuides, an extinct giant Heron from around eastern Arabia.3 This species remains dated sometime between 2700-1800 BCE, and it’s likely that by the New Kingdom this “Giant Bird” would have been increasingly mythologized as claims of witnessing it would diminish, yet remain steeped in more ancient accounts from a time when the bird had a widespread range.

Instead of burying the lead any further, the reason this Bennu is so important to our discussion well beyond a mere etymological association to “Herons” and “breathing life”, but the fact the goddess who was tasked with the unique role as protectress of the Bennu bird was none other than the goddess Nephthys. Obvious is the root “Neph-tu” being nearly identical to our Hebrew term Naphtuhim. While the “House of the Bennu” was the temple at Heliopolis, otherwise known as On, being part of the aforementioned Ennead Nine Gods birthed by Ra, ruler of Heliopolis would help explain this association. Nephthys was not “The god of Heliopolis” but all the Ennead were worshiped in the religious center of Heliopolis.

However, this is not exactly the end of this point. While the “House of Bennu” in the Old Kingdom was certainly Heliopolis, by the time the Bennu bird became affiliated with the Heron proper another shrine in honor of Bennu existed in the VII Nome of Upper Egypt, north of Thebes nowhere near Heliopolis. Like Bennu, Nephthys was considered the “Goddess of Sistrum” in reference to Diospolis Parva (Hwt-Sekhem), the capital of the VII Nome.

Nephthys became increasingly important around the Middle Kingdom, being associated as part of a triad alongside Osis and Isis, or variously Isis and Horus, some of the most important prime gods of Egypt. This clearly shows Nephthys is equally as important as any god during the period, proving clues to why this term was used. We have to ask ourselves, why then was the Torah using the term “Naphtuhim” trying to get us to associate these people with the Nephthys worshippers, and their ever increasingly important cult?

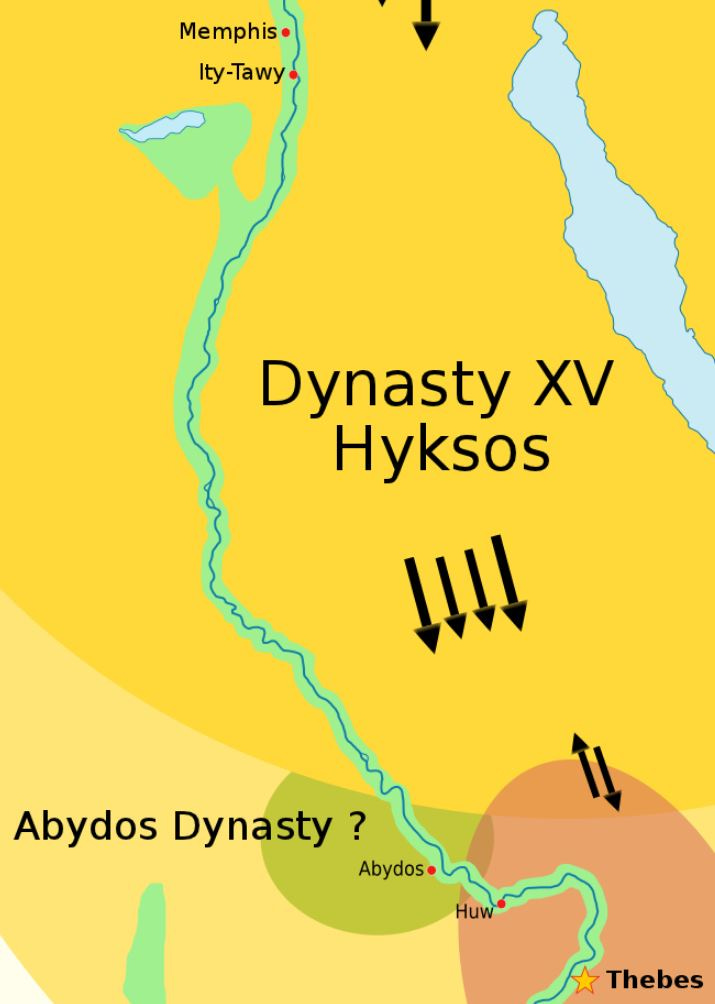

Critical to this question would be the location of Nephthys primary cult centers. As previously mentioned Nephthys had a cult center in the 7th Upper Egyptian Nome capital of Diospolis Parva. The actual name of this city shifted over time, with the modern city referred to as “Hu” or “Huw” clearly coming from the Egyptian name for the city “Hu(t)-sekhem”. During the Greek era the city's appellation was “Diospolis Mikra” which when translated means “Lesser city of Zeus”. When compared with the Greek for the nearby southern city of Thebes, known as “Diospolis Megale” or “Greater city of Zeus”, it becomes obvious that Hut-Sekhem was an extremely important center of activity, arguably being the second most important city in “Thebaic” Upper Egypt by the Ptolemaic era.

Nephthys was absolutely the main goddess of Diospolis Mikra, but her main center of worship by the Ramesside period was much further north in the city of Sepermeru. Conveniently Sepermeru is just south of Faiyum in the XIX Nome along the Bahr Yusuf canal connecting the Faiyum and the Nile, near the modern site of Deshasheh. Nephthys had quite a significant cult here, being roughly equal to the god Set.4 Other than as a religious site, this center was not really used for governance with the significantly more critical site of Heracleopolis Magna not far from Sepermeru being the real locus of control for this region.

Egyptian names for this city refer to it as “Henen-Nesut” or “Hut-Nen-Nesut” with the later clearly drawing parallels to the city of Hu(t), also a center of Nephthys worship, all the way in the south. In a reference found in Isaiah 30:4 we get the line "For his princes were in Zoan and his emissaries reached Hanes”. As mentioned previously Zoan is arguably the furthest point north on the most eastern branch of the Nile closest to Israel, showing this reference is meant as “the north extremes of egypt”. It then follows with the line “reached Hanes” implying the criticality of the geographic distance between these cities within this reference, showing that emissaries went to this so-called Hanes. Many Egyptilogists have identified Hanes as the city of Heracleopolis Magna.5 The importance of Isaiah is that it attests to Hanes/Henen-Nesut as the political capital of Lower Egypt during this period. Emissaries wouldn't have gone there if it didn’t serve a critical governance role in the empire.

Interesting about Heracleopolis Magna is that the city originally comes to prominence only during the First Intermediate Period. It is in this same period that the city reaches its apogee of power, sometime between the year's 2181 and 2055 BCE. By the Middle Kingdom the city wanes in relevance, but by the Third Intermediate Period roughly between 1069-664 BCE the city reclaims its role as a religious and cultural center of Egypt.6 Clearly this city was rarely ever important during the “proper” periods of Old, Middle, or New Kingdom Egypt, and strangely was arguably one of the most crucial cities during times of collapse, and weak centralized Pharaonic control.

While we could seemingly close our discussion here and identify the Naphtuhim with the “First Intermediate Period”, or even roughly located between the cities of Heracleopolis Magna and Diospolis Mikra, there is one more link to explore before we solidify our choice.

During the Second Intermediate Period not far from the city of Huw the “Abydos Dynasty” out of the city of Abydos centralized the only native Egyptian dynasty. The Second Intermediate is often seen as an invasion of Asiatics from Canaan, and not native Pharaohs of “Egypt”, helping exclude them from an “Egyptian” classification as a son of Mizraim. We could claim that the real “Egyptian” center during the Second Intermediate was Abydos, and chiefly the regions between Faiyum/Magna in the north, and Thebes/Mikra in the south. Again, this helps associate Naphtuhim strongly with Intermediate periods.

Finally, we will return to that odd reference to the Noph adversaries who “will attack her daily”. In context to the Naphtuhim as an intermediate period, or a broader representation for ALL intermediate periods of Egypt, it starts to become clear what this reference is intending. Ezekiel is essentially inferring that Egypt will be brought into another intermediate period, where her adversaries will attack “daily” implying a temporal upsetting of the balance in Egypt. As a reference to Egypt being subsumed under Babylon and Persia it helps line up with understanding of the Naphtuhim, and possibly the “princes of Noph”.

Based on all of these clues, our identification of the Naphtuhim should clearly not be with the Memphite, Thebaid, Faiyumian, or even Deltoid peoples. None of these locations has hints related to the term “Naph-tu”, or anything remotely similar. A physical location for these people would most obviously be the “Heptanomis” region which was the territory between the Delta and Thebaid. In this case the Lehabim would be the northern Faiyum while Naphtuhim would be everything south of that, excluding the Oasis which were normally politically integrated with Heptanomis (ironically meaning there were at least nine nomarchs rather than seven). Additionally, associations with Bennu as an unclean Heron god who gave life and would transfer power during periods of Egyptian rebirth make it quite clear that the Intermediate Periods are meant to represent Naphtuhim. This region would act as the unification highway between north and south during each of these intermediate periods, linking the importance of controlling the Heptanomis and thus ending intermediate periods.

Hart, George (2005). The Routledge Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses (Second ed.). New York: Routledge. pp. 48–49.

Also the basis for the Yu-gi-oh Egyptian God “Ra” being a Phoenix.

Hoch, Ella (1977). "Reflections on prehistoric life at Umm An-Nar (Trucial Oman) based on faunal remains from the third millennium B.C.". In M. Taddei (ed.). South Asian Archaeology 1977. Fourth International Conference of the Association of South Asian Archaeologists in Western Europe. pp. 589–638.

'Les Deesses de l'Egypte Pharaonique', R. LaChaud, 1992, Durocher-Champollion

Gauthier, Henri (1927). Dictionnaire des Noms Géographiques Contenus dans les Textes Hiéroglyphiques Vol. 4. pp. 83–84.

The Princeton Dictionary of Ancient Egypt, 2008. Princeton: Princeton University Press. 2008.

This is incredibly well written and comprehensive. So interesting.