Mizraim is universally known as Egypt. Egypt is a term passed down to us through the Latins and Greeks who called the province “Aegyptus”, but this was not the native name for the region. Ancient Egyptians called their land “KMT” or Kemet, meaning “black land”. This term contrasts with the Egyptian term “deshret” meaning “red land” in reference to the desert. There may be another ethnonym referring to Egypt “tꜣ-mry” meaning land of the riverbank.1 Likewise both Upper and Lower Egypt were called Ta-Sheme'aw (⟨tꜣ-šmꜥw⟩) "sedgeland" and Ta-Mehew (⟨tꜣ mḥw⟩) "northland", respectively.

In Linear B we find the term “a-ku-pi-ti-yo” which is likely a Mycenaean corruption of “Hikuptah” which is the Egyptian name for Memphis. This “Akupitiyo” is likely corrupted into Aegyptus in Koine Greek. The modern Arabic name for Egypt “Misr”, comes from the Quran, which got the name from Hebrew “מִצְרַיִם”, again likely stemming from the Akkadian “Miisru”, or the Assyrian “Musur”. Mizraim is absolutely Egypt, and those unable to accept this fact are beyond biblical minimalism.

When thinking about Mizraim it is important to view his sons as ethnicities, or cultures unto themselves despite being part of Egypt. Egypt in this period was not a single ethnic monolith, but a diverse variety of groups who may have shared origin, but developed vastly different cultures, beliefs, and family lineages over the span of thousands of years. Traditional scholarship tends to simply assign regions for each of Mizraim’s children, but as we have seen with Seba, merely assigning a region for a child fails to properly describe what the Torah is attempting to communicate.

We also saw this with Riphath, whose descendants' geographic location moves and shifts through various centuries; this non-regionality is often the case with the sons of a nation. Often those nations - such as Cush, Tiras, or Mizraim - represent a firm geographic fatherland whose descendants may create their own distinct nation groups in later centuries in different locales than their parents. The Israelites indeed distinguished between a “Cushite” and a Mizraite as evident in the line “Miriam and Aaron spoke against Moses because of the Cushite woman he had taken [into his household as his wife]: “He took a Cushite woman!”2

We can therefore say that while all of these groups did originate along the Nile, potential clues for analyzing their origin might lay in other lands, or be based around foreign imported traditions that become identified with the native peoples. Hopefully with an analysis of Mizraim’s lineage we can shine a light on various textual references, as well as provide a better understanding of the people groups that inhabit the region.

Before diving into Ludim, it’s important to frame this discussion by briefly mentioning how Egypt divided its own borders. While we have the previously mentioned Lower and Upper Egypt divides, each half of Egypt was further subdivided into a series of “Nomes” - what are essentially provinces, or counties - each with their own governing dynasties. The governor of a nome was termed a nomarch, being one of the few people in the empire who would answer directly to Pharaoh showing their close integration with regional politics. In various periods of Egyptian history these nomarchs would completely dominate Egypt, with the Pharaoh operating more like a president of the empire and nomarchs having complete power over their province; while in other periods nomarchs would be reduced to intermediaries for the Pharaohs. Egypt in general would operate on a ritualized political system that functioned more like a state enforced religion.

These dynasties often formed familial clans, or even family units, owing to Egypts extremely centralized system of multiple wives for a single leader. This could oftentimes link dynasties genetically to different groups within Egypt, but also help form regional identities. When a new dynasty of Egypt would take over, they would replace regional leaders as they saw fit.

Beyond family these leaders often instituted cultural practices that would spread to the wider population. Frequently this took the form of various new gods that would be worshiped, sometimes overtaking the primary worship figures in certain areas, but other times becoming heavily associated with individual regions. What this means is that while we view “Ancient Egypt” as a singular identity, in the eyes of the ancients, and especially Egyptians themselves, many of these practices would have stood out and oftentimes been points of contention in political power disputes no different from ethnic disputes.

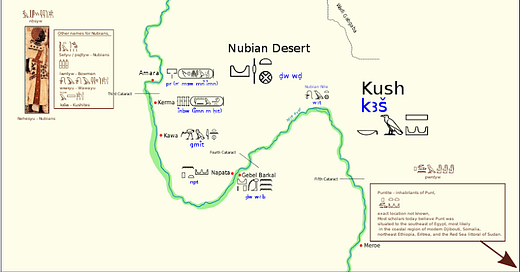

First hand examples of this is in the appellation for the furthest nome in the south, “Ta-Seti”. The term translates to “Land of the Bow” but was often used as shorthand for “Nubia”, and the southern extremes of the empire. Many references to Ta-Seti are intended to be Nubian ethnic references rather than political designations of “rulers of Ta-Seti”, oftentimes it is more like “People of Ta-Seti”. This framework shows how at times, nomes can become regional, and ethnic designations beyond their original usage with their peoples becoming groups unto themselves and necessitating an “-im” suffix that denotes plurality.

The following is a complete map of Egypt, with the nomes. It is essentially impossible to read most of the smaller text, so attached is a link to the larger version.

One of the most important contextual frameworks for understanding Egypt is the obvious position of pharaoh. While many presume the pharaoh was “Egyptian” there was no such ethnic designation and pharaohs came from a variety of backgrounds similar to Roman emperors. I do not entertain racial theories of pharaonic backgrounds, but there is support from alternative traditions for every group's claims to pharaonic origin.

From the Asatir we learn that in the time of Joseph the pharaoh was actually from the progeny of Ishmael!3 We have yet to discuss Ishmael very much, but essentially what is being said here is that a relative of Joseph through his great grandfather Abraham was pharaoh in Egypt which might explain why Joseph was trusted as vizier over the entire empire. We will explore these theories soon, but this could be a reference to the memory of the Semitic Hyksos dynasty who became pharaohs of Egypt around this same period. Josephus also supports this link between specifically “Arabians” and the Hyksos, rather than Isaac’s lineage of Semitic Canaanites.4

The same text goes on to say the pharaoh in Moses’s era was from the seed of Japheth, through his son Kittim. Furthermore, it then says that during the days of Moses a slave of the ‘Rodanim’ became pharaoh. This would imply there were Greek pharaohs - there were Greek pharaohs, the famous Cleopatra being the most notable, except from a much later dynasty - but given the lack of records for this genetic link, it seems tenuous. However, if we are to take the text at face value, it’s possible that these are again Hyksos rulers, who had intermixed with Greeks as many other Canaanites had done due to the archaeologically verified presence of Greeks in the Canaanite homeland of the Hyksos.

The text even includes a supposed lineage: the pharaoh was a son of Gutis, son of Atiss, son of Rbtt, son of Gutsis, son of Rims, son of Kittim, son of Javan. It even asserts that this lineage learned from a certain “Book of Signs” while at Babel, followed by wandering around Nineveh with what seems to be some kind of mystical tradition. Through these magical secrets, the pharaoh’s appear to have gained power in Egypt, a common pattern we saw extensively in our section on Nimrod. Despite the source, the Asatir is essentially placing Mizraim third in line of Ham’s children, helping to explain his placement after Nimrod and Cush, claiming the secrets of the pharaoh’s came from none other than Babylon.

The organization and timing of the children could make sense, but the names do not correlate and seem to come to us through Greek sources rather than Egyptian. The “tis” ending in the names is reminiscent of Manatheo’s claimed pharaoh named “Salitis”, supposed founder of his own dynasty after conquering Egypt from his homeland in an eastern territory.

There is much scholarly work that needs to be done in order to better understand Manatheo’s tradition of pharaohs, and how they link with the Hyksos, but there is certainly some kernel of truth being relayed. Oftentimes, the Asatir is a poor source for history, and itself uses other Greek, Islamic, and Mesopotamian sources to piece together its own material. In this case, it appears the Greeks were asserting earlier dynasties had Greek ancestry in some kind of attempt to provide legitimacy to their later rule, but the link cannot be ruled out. What is possible is there was an attempt to show Egypt was actually the lineage of all of Noah’s children, with the original pharaoh’s being Mizraim, and thus Hamites, a period where the pharaohs were Ishmaelites, aka Shemites, and a later era when they were Japhethites. All three sons of Noah are accounted for, making it a suspiciously convenient insertion.

Resulting from these multivariable ancestries for the rulers of Egypt, it’s very possible the people groups of Egypt were similarly diverse. There is the well known “mixed multitude” from Exodus 12:38 “And also, a great mixed multitude went up with them, and flocks and cattle, very much livestock.” For there to be a ‘mixed multitude’ Egypt had to be “mixed” with something beyond Mizraim’s descendants, giving textual precedence for the diversity of the Egyptian empire. Furthermore, the “Cushite woman” with Moses in Numbers 12:1 also supports that more than “Egyptians” were living in Egypt, even if Cush was a border nation. The Greeks similarly ‘bordered’ Egypt through the sea, and there were many known colonies from the Minoans and Mycenaeans around various Egyptian sites.

It will be important to keep in mind the multi-ethnic background of the Egyptian people moving forward as we frame the Egyptian children as regional cultures rather than a specific genetic people group. Both pharaohs and their Egyptian populace, as we can see through various textual and scholarly sources, was arguably the most diverse location even from the outset of human history.

Breasted, James Henry; Peter A. Piccione (2001). Ancient Records of Egypt. University of Illinois Press. pp. 76, 40.

Numbers 12:1

Asatir, Moses Gaster 1927, pp 247 https://archive.org/details/MN40245ucmf_0/page/n257/mode/2up?view=theater

Against Apion, Flavius Josephus, 14.