Madai

Digging into Indian and Iranian shared ancestry, as well as Zoroastrian theological development

Next we come to what might actually be the most accepted nation of Japheth, the Madai. Madai being a Hebrew corruption of the Assyrian “Madaya”, which was the name for the vast Median empire that sprawled over most of the northern mountains surrounding Mesopotamia, stretching as far as Afghanistan to Anatolia. The Median empire is extremely poorly attested to, and for some strange reason left no written records themselves, but it often intermingled in the later politics of the region as we will see shortly from biblical events helping attest to their existence. The Medes are later replaced by the Persians, more-or-less, essentially usurping the throne of the Medes and conquering additional lands - a formula continued by Alexander the Great when he replaced the Persian Shahanshah.

The Median capital was located in the modern city of Hamadan, which at the time was called Hagmatana, and later Ecbatana by the Persians. Interesting in the ethnic makeup of Hamadan is that the population is not entirely Persian, but has a sizable Kurdish majority; a fact we shortly revisit. The city is actually referenced in Ezra 6:2 as the place where King Darius’s order “was found in a pouch in the citadel of the province of Media one scroll” showing its classical importance even to the Jewish world.

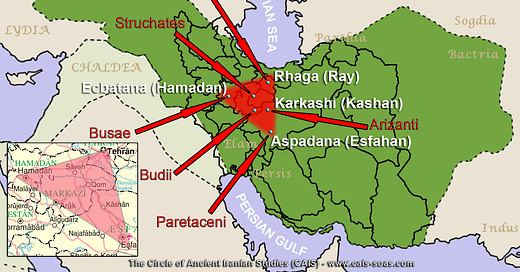

Within this reference the supposed “province of media” likely refers to the “Median Triangle” between the three cultural centers of the Medians: Hamadan (Ecbatana), Ray (Rhaga), and Esfahan (Aspadana). Within this triangle, or province, were the six primary tribes of the Medes that occupied the heartland of what we consider modern Iran. During the Achaemenid Persian period “Media” expands as far north as the Caucuses, encompassing most of Azerbaijan, but is partitioned by the Seleucid Greeks separating Media from “Atropatene” - root of the term Azerbaijan.

Clear from the obvious inclusion of Kurds and the etymological root for Azerbaijan is that the Medes were either closely related to these groups, or these groups descend directly from the Medes. Evidence for this comes from linguistics, where modern Kurdish and Old Azeri - the language spoken by Azeris prior to Turkification of the region - are included inside the Persian “Western Iranian” language family. This “Northwestern Iranian” branch gets quite complicated, and Northern Iran is home to dozens of languages and ethnic groups rather than being an entirely “Persian” country.

Most of these groups trace their origin to various founding populations, but all of them descend from a generalized “Western Iranian” core separating them from the Eastern Iranian languages such as Pashtun, or Old Scythian. Some groups like the Zaza-Gorani languages specifically descended from some form of Median, with a varying degree of Parthian linguistic substrata.1 Others like Semnani directly come from Parthian, showing how many of these groups might trace their origins to any of the numerous Iranian dynasties that unified Persia over its three thousand plus years of history.2

Kurdish specifically is related to the Zaza-Gorani group, part of a wider “Kurdic” family helping attested to these languages coming from a common Median Empire origin, as well as attesting to the Kurds Median ancestry. While their populations have been migratory throughout history, they have roughly occupied these same regions that the Median Empire first unified, and would widely be regarded as “Media” proper. The Kurds for their part are realistically not a “single” Median group, but themselves a complex fusing of ethnic identities over 2500 year's.

The earliest mention of a “Kurd” group separate from Median would be the Carduchoi around 400 BCE living in the mountains north of the Tigris, often sharing allegiance to the Armenians. Soon after the fall of the Seleucids we see the emergence of the Kingdom of Gordyene, often spelled “Corduene” while it was a province of Rome. The people of the province actually worshiped the Hurrian sky god Teshub, rather than an Indo-European god, attesting to that previous relationship to the Hurro-Urartians of Armenia.3

While not critical for our analysis of Madai, an interesting Jewish tradition - widely accepted in Rabbinic literature - identifies a supposed “Qardu” as the landing site for Noah’s ark following the flood. Etymology alone is a poor link, but to leave out this tidbit would be remiss.

Although this identification for Kurds is not always accepted, it’s plainly obvious some large section of Kurds did descend from Media with a portion of them in the province of Corduene. Confusing this puzzle is the existence of a similar people named “Cyrtians” who were neighbors in the Zagros mountains and often employed as Median mercenaries. Most scholars reject a connection between the Cyrtians and Kurds, but it’s possible some section of them fused into the ‘wider Median’ ethnicity that included the entire Northwest Iranian branch.

What is interesting about Median and general Northwestern Iranian is the reality that it is quite similar to Avestan - the language of Zoroastrianism’s holy text the Avesta. Old Avestan even shares much of its grammar and lexicon with Vedic Sanskrit attesting to the shared ethnogenesis for the Indo-Iranian people separate from the “European” branch. Of note is the fact “it shares important phonological isoglosses with Avestan, rather than Old Persian. Under the Median rule . . . Median must to some extent have been the official Iranian language in western Iran"4 showing how the Magi priest class of the Median Empire, that continues its role throughout later Greek and Persian dynasties, was a continuation of the original Zoroastrian elite that descended from a common ancestor with the Vedas.

These Magi are actually attested to as a priest class beyond the “Iranian” lands such as Media, Persia, Parthia, or Bactria, but also among the Sakas and even Non-Iranian lands such as Ethiopia, Egypt, and even Samaria in Israel had Magi priests. Important is that these Magi function in later periods purely as priests without an ethnic identity, and separate from their original Median traditions. While both of these groups may have practiced the same religion, it doesn’t necessarily appear all the Magi are “Medians” which is a critical distinction.5 The Magi priest class are actually the root of the term “Magic”, passed down to us through the Greek term for this group “magos”, with magike being the adjective to describe the activity of the magos. Much of this theistic imagery is taken from the Zoroastrian religion broadly, which was quite similar to elements of Median religion.

Realistically this priest class, and likely the majority of the Medes people, originated in the lands where the Zoroastrian theological tradition first formed. The hypothetical territory for Zoroastrianism was within a sub-culture of the Bronze Age Andronovo horizon called “Yaz”, named after its type-site Yaz Tepe in modern Turkmenistan. Yaz itself was likely a separate entity from the earlier “Bactria-Margiana Archeological Complex” which produced the Oxus Civilization between the year's 2200-1700 BCE.6

Due to the presence of large irrigation systems, stone towers, and sizable houses the sedentary nature of both BMAC and Yaz shows that despite their distinct identities they were much closer to each other than the earlier Andronovo culture which contained mostly steppe nomads, such as the Scythians. Yaz differentiates itself from BMAC by its lack of burial mounds, and gravesites, which probably confirms Yaz was the origin for Zoroastrianism which interestingly shares the practice of exposed open burials.7

Looking at a timeline for all of these empires and cultures mentioned thus far would be quite helpful. Attached is an approximate timeline for the varying Indo-Iranian cultures and their associated periods according to Prods Oktor Skjaervo, Professor of Iranian studies at Harvard.8 All the “Iranian” cultures, both East and West, would be included in the Yaz “Avestan” period, while the “Indo” cultures of India would be part of the Vedic period. Both of these cultures descended from a common Andronovo ancestor population, itself coming from the Yamnaya homeland.

Included in the Medes empire were Parthians, Bactrians, Armenians, Cappadocians, as well as the previously mentioned Persians. All of these people are Indo-European, keeping consistent with the Japhetite theme, but show that Persia was far from a single ethnicity, or group. Many older nations such as the Mitanni, Elamites, Kassites, Gutians or Urartu are incorporated into the Median empire making it one of the earliest multi-ethnic nation states whose governmental framework forms the basis of every empire from the Persians, Greeks, to Romans and beyond.

While some may link the Mitanni to Madai as a people group, the name sounding fairly similar, it would be on false etymological grounds rather than an actual linguistic connection. While the Mitanni were incorporated into this vast empire, they were not the ruling class even if some of their legal structure carried over to the Medians. The Mitanni spoke Hurrian, a Hurro-Urartian language, which in academia has still yet to be placed in any major language family.

As the name implies, Hurro-Urartian was the language of the Hurrians and Urartians, but also the language of the Kassites - who ruled Babylon for a lengthy period and formed a ruling elite across Mesopotamia - likely also fitting into this grouping.9 Potential links for these people groups might indicate a connection to the Elamites, Kassites, and the non Indo-European ‘Kartvelian’ people of the caucuses.

The Kartvellian language is presumed to have come from their own hypothetical “Proto-Hurro-Urartian” homeland of the Kura-Araxes culture, existing around 4000 BCE at the same time as the Yamnaya further north of the caucuses. There are even proposals that place these languages inside a hypothetical “Sino-Caucasian” language family including Chinese.10 This Sino-Caucasian group would actually include Basque, and Na-Dene - a native American language - and would likely represent a branching point between RQ “Indo-European” Haplogroups and NO “East Asian” Haplogroups.

Therefore, based on the reality of Mitanni and other Hurro-Urartians speaking non Indo-European, it is reasonable to presume that the Mitanni are not inside the Japhetite group, and the Mitanni remain of uncertain origin. While these people may not have been technically Japhetites, their culture was more of a ruling elite class that dominated an Indo-European population core as is the case with the Urartians who ruled over the early Armenian groups and eventually genetically mixed into Japhetite groups. This is attested to by the shared vocabulary between Parthian and Armenian whose language contact triggered syntax changes within Armenian.11

However, if we were to bring our timeline for Japheth back a bit and include more than just “Indo-European” speakers but their even earlier proto-language that included Sino-Caucasian, these groups may have split out of Japheth and simply not had the political or territorial relevancy for the Torah to include them in its text. As we have seen with the Getae, and we will see with future nations, most of them were actually fairly relevant to Mid Eastern geopolitics so excluding Chinese and Asian groups would make quite a bit of logical sense.

One group probably included within Madai were the so called “Sigynnae” who appeared to Greek writers such as Herodotus and Strabo to be Iranian. Herodotus claims these people were “north of the Danube”, but Strabo dissents saying they are located around the Caspian, right inside the Andronovo horizon. If we are to believe Herodotus the Sigynnae were “Median colonists” who traversed the caucus mountains and made their way into the pannonian basin of Hungary/Romania.

The reason Herodotus assumed these people were “Median” was due to them dressing in a starkly Median fashion, in other words they wore tunics with sleeves and trousers. Any normal person would find this irrelevant until learning that trousers were not worn by the populations of Europe before the arrival of the steppe nomads, and even among other “Scythian” nomads along the Danube were said to have called them ‘Persians’ or ‘Medians’ variously.12 Additionally, these people owned small shaggy ponies with flat noses that were ill-suited for riding, but could be used to pull carts calling back to the “cart-pullers” of Magog.13 Whether or not the Sigynnae were directly related to the Medians, Persians, or a generalized “Madai” founder; it’s quite obvious they were Iranian.

Another Greek, Apollonius of Rhodes, placed the Sigynnae with the Sindi people who migrated into Europe.14 Notable from the name “Sindi” is the retention of the term “Sind” which likely shares root - or is identical to - the Sanskrit term “Sindhu” meaning river. The river in question is none other than the holy Indus river, central to the development of the earliest Indian civilizations along the Indus river valley. In Iranian this river and everything east - in other words “India” - was called “Hind”, origin for the term Hindu.

Finally let us turn our attention to scriptural references within the Tanakh, starting with the Book of Esther well known as a Persian story. Within Esther the term “Madai” is used frequently, appearing alongside “Paras” nearly four times in 1:3, 1:14, 1:18, 1:19, and appearing solo in 10:2. Obvious from the text is that Paras refers to Persia, and Madai as Media. Many of these references are merely royal terminology, but the final one notes that Mordecai’s greatness was “written in the book of chronicles of the kings of Madai”, strangely placing his story within their cultural milieu.

Esther is far from the only references, as Daniel 9:1 notes Darius was the son of Achashverosh of the “seed of Madai”, and in Daniel 6:9, as well as Daniel 6:13 and 6:16, we get another reference to the “law of Madai and Paras” mentioned in Esther 1:19. The infamous line “Mene Mene Tekel Ufarsin” from Daniel 5:25 has the final term “Peras” reference to the dividing of the Kingdom being given to Madai and Paras. Yet again, Daniel 8:20 refers to the “two-horned ram” as the kings of Madai and Paras. Even Isaiah 21:2 mentions besieged Media in one of the prophecies. Clear from all of these references is that “Madai” is essentially the same thing as Persia, and often the term Madai is even used when referencing Persian/Iranian lands more broadly.

Potential clues might be found in the Book of Jubilees; while not considered canonical in Rabbinic Judaism the text is seen as canonical for the Beta Israel Ethiopian Jews. Reportedly this Midrashic work proposes that Madai married a daughter of Shem, and preferred to live among Shem’s descendants rather than dwell in his allotted territory “beyond the Black Sea”.15 What is interesting about the text is that it suggests Madai occupied a land “west of his brothers Gomer and Magog” indicating something even more westerly than France or Germany where Riphath lived. The only proposed location west of continental western Europe would be the British Isles, indicating that the original territory of Madai might have been intended for Britain. While the text can be viewed as a sort of non-canon Midrash - or pseudo-mythical narrative - it helps offer a look into the way ancient populations would have been thinking about these people groups.

Clear from this look into Madai should be the not just the “Median” origin for these people, or the broader “Iranian” origin shared by more than just technical Iranians, but even the inclusion of “Indo-Iranian” sections of the Indus valley with the Madai people, or civilization. While a proposed ethnogenesis happened across the Andronovo horizon, with later elements of the Yaz culture fusing into them as a ruling elite, all of these Proto Indo-Iranian groups again come from that original hypothetical “Yamnaya Indo-European homeland” of Japheth.

I will leave the final public chart for Japheth’s children as the conclusion of the post, but note that anyone already subscribed when these charts are paywalled will be permanently grandfathered in and have nothing to worry about.

Hopefully you enjoyed this weeks post despite it arriving at a well-known and accepted definition of Madai. Throughout there was a variety of information that helps one contextualize who, and what “Madai” really means beyond a simple understanding of “Persian”, often meant to be the Persian Empires and wider Indo-Iranians, but in the modern eye viewed as “Persians”. Shedding light on the complexity of these cultures is the goal of these posts, as well as using the Torah to teach and expound on adjacent topics.

This post marks the halfway point within “Book One” focused on Japheth. For those keeping score at home, that’s about 30,000 words if you’ve actually read everything; you aren’t alone in thinking this has been an extremely dense discussion. I am still considering publishing this work independently off Substack, but that may be left to a time when the audience for the work is larger than a minyan.

I may also pause publishing of sections after the conclusion of Japheth, briefly, and begin producing a series of YouTube videos on the subject, but I would ask you, the readers, if you think that sounds interesting. YouTube might be a good way to slim down these topics, and explain them in more colloquial - less academic - language.

The pause would be short lived, as nearly the entire section on Ham (45,000 words so far) has already been prepared. The vast majority of the content has been fleshed out, and merely needs editing with the final sections of Canaan’s eleven children left to write, and the beast that is Nimrod. Nimrod should be lengthy, if not the most length of all sections, and will bring the material content to over 60,000 words in Book Two, for a combined 120,000 words. Completing even a fraction of this so far has my deep appreciation.

Next week will be an extremely small section on Javan, before unraveling the complex origins for his sons Elishah, Tarshish, Kittim, and Dodanim. We will deviate from most of the previous content, especially the Scythian variety, and look at the Mediterranean civilizations which will play a role in macro Near Eastern politics.

Borjian, Habib (2019) Journal of Persianate Studies 2, Median Succumbs to Persian after Three Millennia of Coexistence: Language Shift in the Central Iranian Plateau, p. 70

Pierre Lecoq. 1989. "Les dialectes caspiens et les dialectes du nord-ouest de l'Iran," Compendium Linguarum Iranicarum. Ed. Rüdiger Schmitt. Wiesbaden: Dr. Ludwig Reichert Verlag, p. 297

Olaf A. Toffteen, Notes on Assyrian and Babylonian Geography, The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures, pp.323-357, 1907, p.341

Skjærvø, Prods Oktor (2005). An Introduction to Old Persian (PDF) (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Harvard.

Zaehner, Robert Charles (1961). The Dawn and Twilight of Zoroastrianism. New York: MacMillan. p. 163.

Lyonnet, Bertille, and Nadezhda A. Dubova, (2020b). "Questioning the Oxus Civilization or Bactria- Margiana Archaeological Culture (BMAC): an overview" , in Bertille Lyonnet and Nadezhda A. Dubova (eds.), The World of the Oxus Civilization, Routledge, London and New York, p. 32.:

Parpola, Asko (1995), "The problem of the Aryans and the Soma: Textual-linguistic and archaeological evidence", in George Erdosy (ed.), The Indo-Aryans of Ancient South Asia: Language, Material Culture and Ethnicity, Walter de Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-014447-5 p. 372

Skjaervø, P. Oktor (2012). The Spirit of Zoroastrianism. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-17035-1.

Schneider, Thomas (2003). "Kassitisch und Hurro-Urartäisch. Ein Diskussionsbeitrag zu möglichen lexikalischen Isoglossen". Altorientalische Forschungen (in German) (30): 372–381.

p. 205. Kassian, Alexei. Review of The Indo-European Elements in Hurrian. Journal of Language Relationship • Вопросы языкового родства • 4 (2010) • Pp. 199–211.

Olbrycht, Marek Jan (2000). "Remarks on the Presence of Iranian Peoples in Europe and Their Asiatic Relations". Collectanea Celto-Asiatica Cracoviensia. Kraków: Księgarnia Akademicka. pp. 105–107. ISBN 978-8-371-88337-8.

Batty, Roger (2007). Rome and the Nomads: The Pontic-Danubian Realm in Antiquity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-198-14936-1. P. 200-202.

Olbrycht, Marek Jan (2000). "Remarks on the Presence of Iranian Peoples in Europe and Their Asiatic Relations". Collectanea Celto-Asiatica Cracoviensia. Kraków: Księgarnia Akademicka. pp. 105–107.

Machiela, Daniel (23 October 2009). The Dead Sea Genesis Apocryphon: A New Text and Translation with Introduction and Special Treatment of Columns 13-17. ISBN 9789047443018.

This was an excellent read! Thank you so much. I’m wondering whether here you have had any chance to examine “Tur” or the “Turanians” or named otherwise in the Table of Nation. Cheers

good job Benj very interesting