We turn to the only son that preserves “Yaphez” - the Hebrew name for Japheth - with the original “Ya” sound, Javan. Pronounced closer to a ‘Y’ rather than a ‘J’, already we can see a maintenance of the “Io” sound found in later Greek, giving an immediate indication that Javan is located somewhere in Greece proper unlike any of the previous children. The Ionian mythological forefather was called “Ion”, while the native people of Greece, the Mycenaeans, called the Ionians by the name “Iawones” flipping the V and W sound similar to its usage in Latin, a related people. Even in Sanskrit, another closely related Indo-European language, the Greeks are known as “Yavana” rather than a cognate of Ionia. Even within the Book of Daniel, what I would consider a primary source on the geopolitics of these people and their descendants, Javan is associated with a great King of Greece certifying the traditional location for Javan’s descendants.1

Likewise, Javan’s sons are often related to Greeks and their associated peoples. At first glance this might seem difficult to understand, but we must remove our modern interpretations of what we see as “Greek” and view it as a complex merging of ethnicities. Javan and his tribe only represent one of the four principal Greek tribes; however all the other tribes may variously descend from Javan. In much the same way Abraham is the progenitor of both the Jews and ‘Arabs’ (a term that includes multiple tribal identities in one broader grouping), Javan can be the progenitor of the Ionians and broader Ionians.

Even within Greek history, the Ionians take command of the Delian League and wider Greek coalitions against the Persians, and at that time the “Javanites” would have certainly been the leaders, if not outright progenitors, of the Greek peoples. However, at times this position of prime Greek leader was challenged by groups such as the Dorians, known famously for their aggression against Athens from the city of Sparta during the Peloponnesian war. The Spartans themselves were challenged, and defeated, by the Theban League, itself a rival to the Athenians. Ironically, none of these coalitions technically “unified” Greece, and it was the Macedonian’s under the famed Alexander the Great who unified under the League of Corinth.

When it comes to Greek, the language is crucial to understanding their polities and alliances. Javan and the Ionians were speakers of Ionic, which begs the question what the other speakers of Greek actually spoke. We can clearly define three broad language groups: The Western group, composed of Doric, Northwestern and Achaean, the Central group of Aeolic and Arcado-Cypriot, and finally the Eastern group of Ionic/Attic. Each of these groups came together to form what we would call “Greek”, later adding Macedonian to the mix which was actually not considered classically “Greek” by the other Greeks as was actually the source of ostracization for Aristotle when attempting to interact with the classically Greek school of Plato/Socrates in Athens, forcing him to move to Macedon triggering a series of events that culminated with Aristotle tutoring the young Alexander personally. It was earlier mentioned there are four tribes of Greeks, and while one may assume the final is Macedonian, at one point in time the Dorians were the fourth ‘tribe’ of Greeks. This only furthers the example of how a grouping of people can gain, or lose individual tribes to form their national identity.

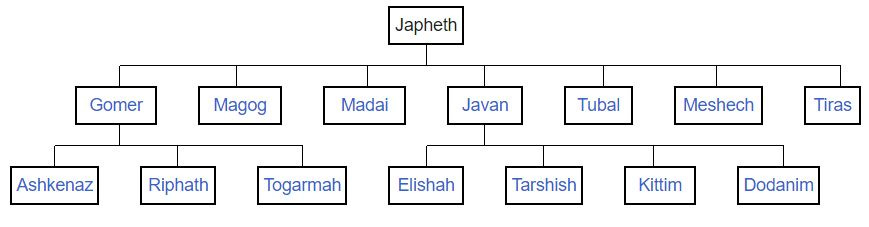

Javan has four sons, coincidentally correlating with the same number of tribes of Greeks, many of them being named after areas of Greek colonization. We additionally know that during Greek colonization in the 8th through 6th centuries Greeks had colonies as far as Spain and southern France, and east in connection with the previously mentioned Yamnaya homeland on the river Don, in addition to the entire Pontic sea. On the attached map the Greek colonies are visible in blue, showing the sheer extent of their domination of the coastal territory of the Mediterranean. What is of note is that nearly the complete Pontic coastline is colonized by Greeks putting the Greeks, and Javan, as a sort of seafaring branch of the Japhetites. This “seafaring” element will be important in later periods, and tends to characterize many of the Greek’s epic mythology. Most identifiably the Iliad and Odyssey, but also the story of Jason and the Argonauts recant long seafaring voyages of tribes of men across the Mediterranean. In later chapters we will discuss these seafaring voyages, and the historicity of the events in connection with other nations' records of the Bronze Age Collapse. This contrasts with the “Nomadic” steppe people who are more associated with equestrian traditions similar to the Macedonians who were often considered “not Greek” despite being culturally Greek.

Leading up to the period of the Israelite Kings, rather than being occupied by any of the Greek ethnic groups mentioned thus far, Greece is instead occupied by the Mycenaeans. Rather than any of the four tribes of Greeks, the Mycenaeans are essentially contiguous with the later Greek peoples broadly, albeit with a larger steppe admixture. Mycenaean is known as “Linear B” and is likely a form of Proto-Greek demonstrating Mycenaeans are an early population of Indo-European Greeks.2 We will discuss these groups at length in later sections, and how the Mycenaeans themselves were likely not the indigenous group, nor related to the native peoples such as the Pelasgians.

Before moving forward with the coming sections it is incredibly important to restate that during such a migration heavy period a name for a specific city, or place location does not identify that place with the tribe of the same name. They can, but they do not always, like in the case of Tegerama and the Luwians. While the individual with that name may have founded the city, they might have also continued elsewhere only leaving descendants, or a noble elite to rule over the locals. Thus studies on genetics are not always a precise identifier, nor can etymology be relied on alone. The full picture only becomes clear through sequential and geographic context.

I will leave you here with a short post for this weeks entry as we prepare to unravel the subdivisions of the Greeks over the following four names on the Table of Nations. Next week we will pick this story back up with Javan’s first son Elishah.

As always please like, comment, and subscribe if for some reason you’ve actually read this far and have yet to subscribe. If there are any previous subjects you would like elaboration, or clarification on, please feel free to contact me, or leave a comment. Thank you once again for reading, and I hope you’ve learned something from this weeks entry.

8:21-22 and 11:2

Chadwick, John (1976). The Mycenaean World. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29037-1. p. 617.