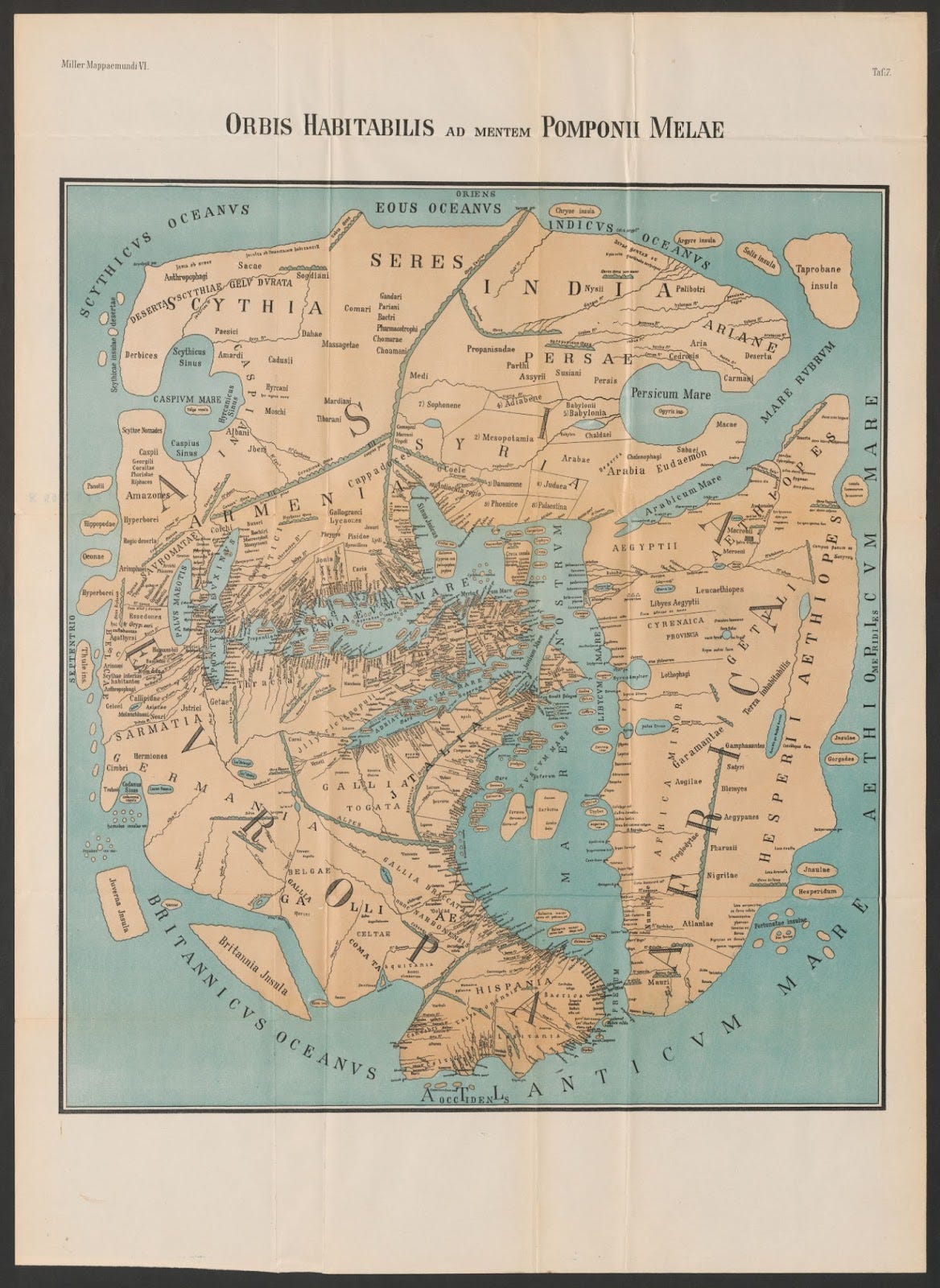

Greeks and Romans both believed the Nile may have stretched around the entire continent, however, this was not the extent of their geographic curiosities as they believed the Sahara stretched all the way to the Western coast, terminating in the Atlantic Ocean. In fact, the Southern Atlantic had a separate name up until the 19th century, called the “Okeanos Aithiopos”, a borrowed term from Greek.1 Clearly this region was “Ethiopia”. They didn’t perceive any rivers along the Western coast of Africa, or the lush tropical forests of the Kongo. They viewed much of this as no man's land, and didn’t process the size of the continent. Let’s turn to one of the most famous maps of the period, reconstructed from Roman geographer Pomponius Mela’s 43 AD “De situ orbis libri III” where he lists locations for the entirety of the world.

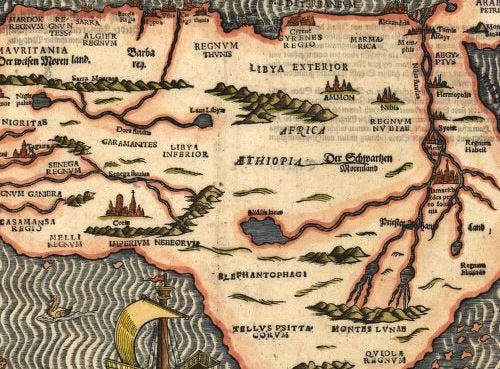

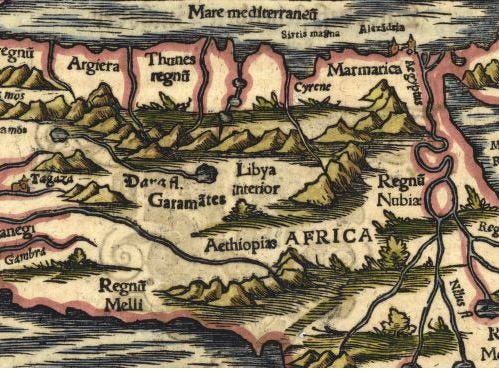

Much of the map might be difficult to read, and can be searched separately, or viewed through the footnote2, to view pieces blown up, but importantly we see two massive words “Aethiopes” on the left most continent labeled Africa. One of these Aethiopes is located along the Red Sea, in the traditional Ethiopian highlands while the other is placed interestingly in West Africa of all places. This affirms the Roman belief that Ethiopia was encircled by a great sea, and terminated at the end of southern and western coastal africa. Saving the lengthy descriptions of how the ancients viewed Africa, we can see from two other maps from 1581 and 1590 respectively that even well into the 1500s this region was still called “Aethiopia”.

On all of these maps it's quite clear that there was a “Western Ethiopia” located around West Africa, presumably the same location Josephus was referencing in his mention of Dedan. We can even see that “Libya” in this period stretched much farther west, well into Mauretania, and will become crucial to our later discussions of Put.

Even stranger we have mention of “White Ethiopians”, quoted from Pliny’s Histories: “If we pass through the interior of Africa in a southerly direction, beyond the Gætuli, after having traversed the intervening deserts, we shall find, first of all the Liby-Egyptians, and then the country where the Leucæthiopians dwell.” We can see they believed past the Sahara were so called “White Ethiopians”, but it’s possible this is an example of colors being used for regional designation rather than ethnic ones.

The Greeks believed the Nile began at the Atlas mountains, but by the time of Rome this idea had clearly been disproven based on the map of Pomponius Mela. We get further designations from Pomponius Mela who says that "On those shores washed by the Libyan Sea, however, are found the Libyan Aegyptians, the White Aethiopians, and, a populous and numerous nation, the Gaetuli. Then a region, uninhabitable in its entire length, covers a broad and vacant expanse." It becomes obvious that until the colonial era, much of Africa was considered “Western Ethiopia”, and the term “Ethiopian” was often used by the classical world to simply mean “black people”. While the Torah does not use such simplistic designations, Dedan may indeed be referencing a people further west - rather than in the highlands - with potential links to the traditions of Ethiopia.

We know the Sudd, the marshy swamp territory just north of the African jungles, was the limit of ancient knowledge of the region, but they believed this wetland was fed by the Nile, which snaked into the Niger river. The furthest expedition down the Nile was actually a result of the Emperor Nero, who may have intended to conquer Nubia and Ethiopia to incorporate them into Rome.3 Finding this land incredibly inhospitable and prone to illness, it’s likely this was abandoned. While this was the only expedition into the Sudd, there were a few Roman expeditions towards West Africa, through the Sahara. Most of these expeditions failed to penetrate very deep, possibly reaching Lake Chad, the Niger river, and somewhere near the Senegal river. None of them navigated these rivers further, and never found their origin or disproved if these rivers did indeed reach the Sudd. It’s likely the Roman’s knew the Niger, and Lake Chad, did not feed into the Nile.

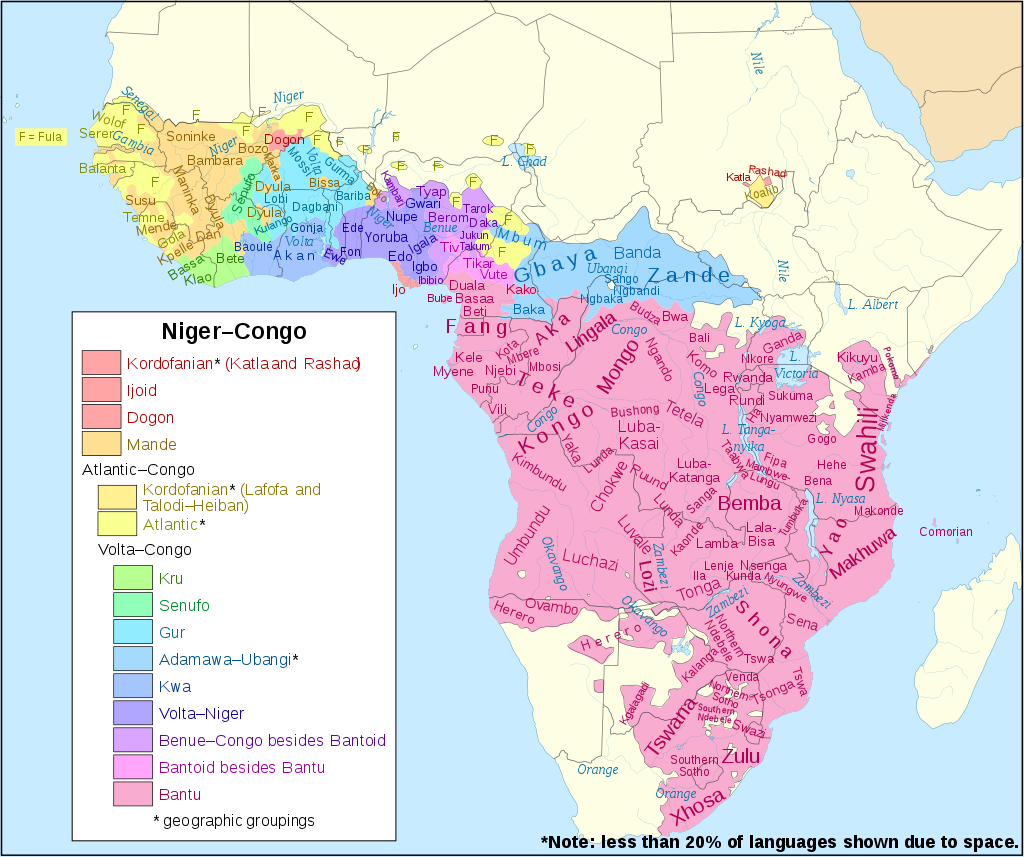

Having certified the location for the Eastern Ethiopians it would be pertinent to discuss the oldest Kingdoms and people in the region. This is a difficult task as nearly all of the records for this region are lost, and only contained in oral traditions of the ethnic groups. Our search can begin in one of two places, either with these oral, linguistic traditions and how they linguistically shifted over time, or with the ethnic groups themselves. Due to the critical importance of oral traditions, it would seem more obvious to start by analyzing how these language groups evolved.

All of these languages are part of a hypothetical Proto-Niger-Congo language family that began to split up around 8000 BCE around the Sahel and Southern Sahara during a period known as the “Green Sahara”.4 During this phase nearly the entirety of modern Niger-Congo regions would have been inhospitable and lack human settlement due to the dense forests that would have coated the area. However, the region north, known today as the Sahel, would have been a luscious green paradise of sorts where hunter-gatherers wouldn’t have their dietary needs stressed. All African cultures, including the Ancient Egyptians, trace their cultural ethnogenesis to the Green Sahara, with evidence that shows some level of sophistication due to the presence of early shipbuilding and complex cave art.

We need to narrow our search down by excluding certain groups based on certain traits. Notably anything we have already provided a likely identification for is unnecessary. This means Nilotic speakers - but potentially not their Saharan brother groups - and the Semitic speaking groups in the Horn of Africa such as Ethiopic ‘Abyssinians’ and Somali. I would also find it necessary to exclude most waves of nomadic people associated with the Islamic Arab migrations. This includes the obvious Arabs and Amazigh, but also the Fulani and importantly Hausa whose ethnic origins stem from a later splitting off of Nilo-Saharan speakers who adopted Arabic at a separate date and moved into the Lake Chad basin.5 It would also be less obvious, but still necessary to exclude the central-southern Bantu and eastern Swahili who find their ethnogenesis in much later periods.

Previously we mentioned the Kordofanian language family of the Nubian hills that falls within this macro family, but the jury is still out regarding when this group broke off from the rest of the family, and how they became geographically isolated. This leaves us with a short list of potential candidates: Kanuri, Mossi, Mande, Akan, Igbo, and Yoruba. While all of these groups have close brother groups, they are some of the largest and oldest ethnicities in West Africa.

Next time we will begin looking at each of these groups, and their histories, myths, and genetics to give us a better picture of West Africa in the classical era.

1799 James Rennell map with the Aethiopian Sea in the Gulf of Guinea area.

Buckley, Emma; Dinter, Martin (3 May 2013). A Companion to the Neronian Age. John Wiley & Sons. p. 364.

Blench, Roger. 2016. Can we visit the graves of the first Niger-Congo speakers?. Paper presented for the 2nd International Congress "Towards Proto-Niger-Congo: Comparison and Reconstruction", Paris, 1-3 September, 2016.

Williams, Floyd A. (2009). "The Genetic Structure and History of Africans and African Americans". Science. 324 (5930): 1035–44.