In the very north starting at the 1st cataract was the Kingdom of Nobatia. This Kingdom clashed with the desert people to the east called the Blemmyes, who are attested to as far back as the 7th century BCE, and likely inhabited the city known as Kalabsha near Aswan. These Blemmyes are possible candidates for the progenitors of the modern Beja people, indigenous to the eastern desert as far back as 3000 BCE, however they never occupied the Nile proper. Before being Arabized, the Beja spoke the eponymous Beja language, a form of Cushitic. We could thus call the Lower Nubian, or Bejan people as one branch of Ham’s lineage, but they never formed any certifiable Kingdom and would thus be more like great, great grandchildren and left off the list specifically, and maybe grouped with the wider Cushitic speakers.

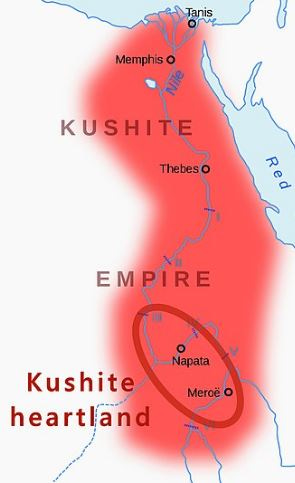

Eventually Nobatia is conquered itself and was incorporated into the Kingdom of Makuria, which existed for over 1000 years as an independent Kingdom in the region. Makuria developed around the Kush heartland in Upper Nubia, centered around the cities of Napata and Meroe. However, these cities were shells of their former glory and the real locus of power shifts up the Nile to the city of Dongola. While both the upper and lower regions are referred to as “Nubia” this isn’t ethnically correct. The “Nubians” only moved into the Kingdom of Kush around Nobatia and Meroe in the 4th century, and were contained in the Lower Nubian regions during the entire period of the bible. Eventually these Nubians make their way south and begin settling in what is “upper nubia” giving the modern name to the region.1 Accordingly these Nubians even clashed with the local Kushites of the south,2 and by the 4th century AD occupied the entire region of Nubia, but were contained around Meroe and didn’t progress further south.3 Despite coming from the north and occupying the south, the “Nubians” would thus be the Lower Nubians, with the Upper “Nubians” being “Kushite”. Due to their lineage coming from the old Kushite Kingdom, these Makurians can be called the ‘original Kushites’ and be considered part of Upper Nubia in Ham’s lineage. Nobatia and Makuria combined are therefore “Lower Nubians” that moved south, and identified with the Kerma culture.

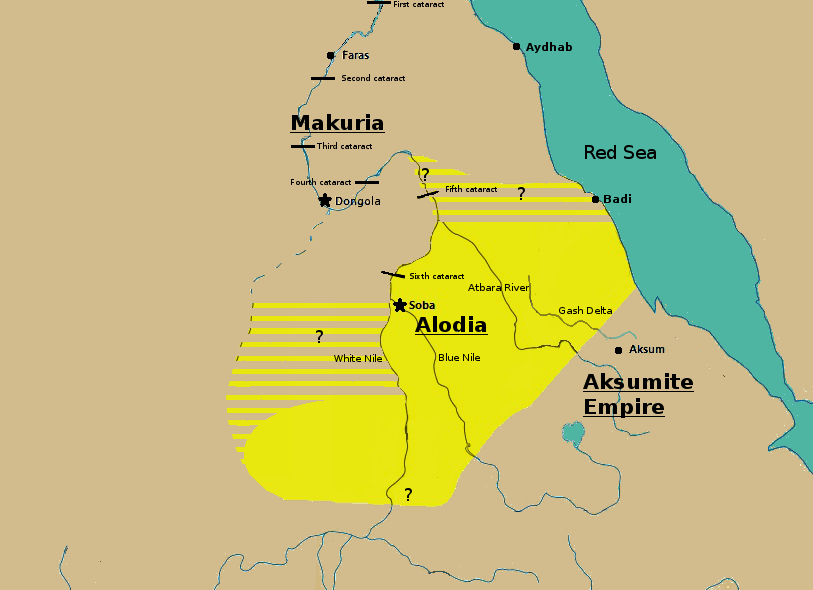

Finally we turn to the third major kingdom that pops up in the region called “Alodia”. Alodia is a corruption of the Arabic term “Alwa” or possibly the Greek “Aloua”, but either way all these terms are likely related to the 4th century term appearing on a Kushite stele referring to a people south of Nubia called “Alut”. The Alut>Alod transformation becomes obvious making this Kingdom certifiably “separate” from a Nubian ethnic perspective as if the Nubians viewed them as related they wouldn’t have given them separate identification in their own records. Who, or what sort of Kingdom existed in this period and earlier is completely unknown due to the sparse archeological records present. As has been discussed before, much of modern archeology is plagued with political aspirations and propaganda, especially in countries without the monetary capital necessary to investigate their heritage. Being located in the war torn country of Sudan makes it difficult to perform any serious work, and much of the region may be better left untouched for a less tumultuous period.

We do know a few crucial facts regarding Alodia, which was centered around a region called Gezira, a fertile plain at the key terminus of the White and Blue Niles. We know from inscriptions that the Alodian’s were polyethnic, and therefore spoke multiple languages including the aforementioned Nubian in later periods.4 Their native language is perhaps “Alwan Nubian”, only known to us through a sparse number of inscriptions. If we had more archeological data we might be able to reconstruct their language, but currently this isn’t possible to achieve. We do know that in the hill country to the south there were multiple Kordofanian languages spoken. Kordofanian is a branch of the Niger-Congo family, the major African macro language group comprising the entirety of indigenous West, Central, and East Africa. The only place Niger-Congo isn’t spoken is in the south which is populated by the migratory Khoisans.

Crucially we know that Alodia’s capital was a place called “Soba” near the confluence of the aforementioned Blue and White Niles. Soba is located not far from modern Khartoum, the capital of Sudan with an urban population of six million. Khartoum was reportedly established in the 1800s, and the more critical center of Soba was the power base of the empire. However, based on archeological records from the area of Kadero, just north of Khartoum, we are able to glean a few key traits of the people occupying the Gezira region around 3000 BCE.

Most important from Kadero is the number of records indicating the presence of cattle, and dairy. The inhabitants were most likely pastoralists, a form of animal husbandry which sees the cattle released onto the land to graze. The owners of the cattle are nomads who migrate around regions, which correlates well from what we know of present Nilotic speakers' traditions. Conveniently, Kadero shows the earliest evidence for cattle based pastoralism in the region.5 However it is not merely cattle grazing that is present, but a large number of cattle bones possibly indicating a ritual usage of cattle sacrifice.6 Also found is evidence for the early adoption of dairying, an experience that wouldn’t be universal to most other Africans.7 We can thus view Kadero as the “Early Khartoum Culture”, and our most likely candidate for Nilotic speakers distinct from the “Kermites” and “Kushites” in the north.

Interestingly these Nilotic speakers likely extended as far south as a marshy wetland known as “The Sudd”; a nearly impassable region until the modern era. It is unlikely Nilotic speakers had pushed further south than the Sudd until the 14th century, caused by pressure from Arab traders moving into Sudan/Nubia.8

Due to the shifting waters of the Nile, cities rarely stick around for thousands of years, and if they do their core is often buried under a pile of silt, or underwater like much of modern Egypt thanks to the Aswan dam. Even worse, an estimated 1% of Soba has been excavated making any real information on the city impossible.9 To really bring home how impossible archaeology of this region would be; both the 1973 US hostage crisis caused by palestinian terrorists of Black September, and support by palestinian leader Yasser Arafat, occurred in Khartoum. Even wilder is the fact that in 1991 Osama bin-Laden purchased a home in Khartoum, as well as another home in Soba! This entire region is a stronghold of islamic propaganda, and it’s unlikely any western archeologists will be able to dig up anything non-islamic for the foreseeable future.

Obvious to a sharp eyed reader is that the “S-ba” name is only one vowel shift off from Seba, Cush’s first son. How these names connect is entirely unclear, and may not be until further archaeology is performed, but Soba could be another case of the “Alexander Effect” where a founder of a city doesn’t necessarily represent the inhabitants ethnically. Perhaps looking at some of the groups in the region might get us as close as we can come to an understanding. Sadly we do know that around the 4th century AD the height of the Alodian power had waned possibly due to their conflicts with the powerful Aksumite empire on their border, further up in the highlands of the river. Three centuries later, Islam arrives on the doorstep erasing any pagan ethnic groups in the region.

There are two very notable ethnic groups related to the collapse of the kingdom of Alodia, and Nilotics: The Dinka and Maasai. Both are Nilotic branch speakers with a heavily pastoralist way of life, shown on the attached map. Thankfully both of these groups have strong, fairly well known oral traditions that do discuss both of their origins.

According to Dinka scholars, they originated in none other than the region of Gezira some time around the 12th century AD, and likely migrated out following the collapse of Alodia.10 Dinka have argued that the name “Khartoum” originates in Dinka and means “place where rivers meet”.11 Anyone who encounters a Dinka would be struck by their massive height, and they are arguably the tallest people of Africa. While height is seemingly unimportant in this picture it does often signify nomadic versus settled groups and it lines up with their related Nilotic brethren, the Maasai, who are arguably another contender for tallest in Africa, implying shared origin.

Immediately noticeable again from their height, but also their vibrant incredibly colorfully dyed clothing, the Maasai are a dominant tribe of two million located in the modern nations of Kenya and Tanzania. DNA studies of the Maasai - as well as other Nilotic groups - indicate that over the past 3000 years these people have assimilated heavily with Cushitic speakers in the east, going beyond mere linguistic relations, but also sharing the genetic mutation associated with lactose tolerance.12 This heavy emphasis of dairy again lines up with what we know about the domestication of cattle by these nilotic people around Gezira. These same studies show that the Maasai culture was retained in spite of this admixture, and may represent one of the rare cases where a cultural substrate isn’t wiped out by an intermarrying patriarchal group. Based on these studies, the Maasai are closely related to other Cushites, and this is likely the case for many other Nilotic peoples still untested.

Turning our attention to the language of the Maasai called “Maa” the word “khartoum” means “we have acquired” and that the location of modern Khartoum, in other words Soba, lines up with where the oral traditions of the Maasai claim their ancestors first acquired cattle.13 This also lines up completely with the archeological records from Kadero we previously mentioned that show domestication of dairy animals occurred in this homeland. While this name doesn’t imply anything regarding Soba’s founding, it does show that Nilotic peoples, such as the Maasai and the Dinka, were indeed “around Soba”, and formed their ethnogenesis in the region. Even according to the Beja, in the Bejan language - while not Nilotic speakers it is a sub branch of Cushitic - the word “hartoom” means meeting, mostly certifying the Nilotic meaning for the place being something related to a “meeting point”. Perhaps this was a major location where tribes would meet and return to, or this is related to the meeting of the two rivers, but we can confirm through all this oral evidence that Soba was Nilotic and Cushitic.

While we have so far only discussed the “Nilotic” peoples located around the Nile, the closely related “Saharan” languages are grouped into a wider Nilo-Saharan group. What is interesting to note about these people is they seemingly maintain strong traditions despite making up an ethnic minority of the regions they inhabit. Oftentimes these people are the ruling class of nobility, or the sultans of great empires. Notable among them are the Saharan Gao Empire, Songhai Empire, Kanem-Bornu Empire, and numerous smaller kingdoms and “empires” in the Sahel region. Other Nilotes such as the Rutara, Tutsi, or previously mentioned Maasai established strong Kingdoms for themselves in a region filled with Bantu speakers. They would often adopt the Bantu language, but maintain Nilotic traditions, and lifestyles.

It is difficult to precisely explain the origin of the term Cush, or who the “Kerma” actually were, but we can be certain this region, or nation, is the intended identification of Cush. Perhaps if the ancient Cushite traditions had been written down we could gleam more about this supposed “Cush” founder. While Cush may be easily identified with Kerma, and possibly the Lower Kushites, the full ethnic picture of the region and surrounding territories is more complex than merely Lower Kush. Much like with Javan who represents a “unified Greece” under Ionian leadership or the later Mizraim, well known to represent “Egypt” as a composite whole, it is likely “Cush” represents the composite whole of Nubia, Kush, and the various Kingdoms that form Empires south of Egypt all with some sort of Ethnogenesis related to the Kingdoms of Kush, and Lower/Upper Nubia. Let us then turn to Cush’s children in order to fully unravel the “Cushite” picture.

That’s it for Cush. Next time we turn to his first son Seba, briefly introduced in this section. Don’t forget to like and comment your thoughts on the direction of Ham so far since I’d love to know early in the process so I can cater the experience better over the coming posts.

Rilly 2008, p. 211

Rilly 2008, pp. 216–217.

Hatke 2013, §4.5.2.3.

Zarroug 1991, pp. 88–90.

Barakat, HalaNayel (1995). "Middle Holocene vegetation and human impact in central Sudan: charcoal from the neolithic site at Kadero". Vegetation History and Archaeobotany. 4 (2)

Haaland, Randi (2012). "Changing food ways as indicators of emerging complexity in Sudanese Nubia: from Neolithic agropastoralists to the Meroitic civilisation". Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa. 47 (3): 327–342.

Dunne, J.; di Lernia, S.; Chłodnicki, M.; Kherbouche, F.; Evershed, R. P. (2018-03-25). "Timing and pace of dairying inception and animal husbandry practices across Holocene North Africa". Quaternary International. African Archaeozoology. 471: 147–159

Robertshaw 1987, pp. 177–189.

"Soba – a new research project in Sudan". pcma.uw.edu.pl. Retrieved 2020-07-28.

Beswick, Stephanie (2004). Sudan's Blood Memory. University of Rochester. pp. 29–31. ISBN 1580461514.

Room, Adrian (2006). Placenames of the World (2nd ed.). McFarland. p. 194. ISBN 0-7864-2248-3.

(2009). "The Genetic Structure and History of Africans and African Americans". Science. 324 (5930): 1035–44. Bibcode:2009Sci...324.1035T. doi:10.1126/science.1172257. PMC 2947357. PMID 19407144.

Donovan, Vincent J. (1978). Christianity Rediscovered: An Epistle from the Masai. Orbis Books. p. 45.