The earliest form of this name appears on the Temple of Kom Ombo, from a description for a possible region that reads “Kasluhet”.1 Helpfully the name is the same as Hebrew, excluding the ‘-im’ suffix as usual. Ombos, known as Nubt in Egyptian, was actually the capital of its region and a garrison town under every dynasty of Egypt through the Roman period. It is unlikely Ombos specifically is the identification for the Casluhim, but they may have come from, or moved to the region in some period. If the Casluhim came from Ombos, or somewhere near there, this does interestingly put their origin in the Aswan area where Egypt and Nubia split, but had its own merging of cultures. In pre-dynastic periods this region was the location for an overlap between Kerma and the C-Group culture, possibly indicating a separate ethnogenesis.

Looking at later written records, Josephus mentions the Casluhim in Antiquities of the Jews I vi 2 as one of the Egyptian people who had their cities destroyed during the Ethiopic War, and as a result were lost to history. We must remember that if Josephus is correct and the Casluhim lost their cities during the supposed Ethiopic war, then finding any major settlements of these people in a later period is quite unlikely.

This supposed “Ethiopic War” is most probably a memory of Pharaoh Thutmose II where upon his coronation Nubia immediately revolted.2 Thutmose sends his army into the region under the control of his father’s generals who appear to have easily dispatched the Nubians.3 If this war was easy, it’s likely the retribution following was a complete destruction of the people, or potential forced resettlement of what remained. While the reign of Thutmose is debatable it was sometime around 1500 BCE in all accounts, but we do not have further records of this campaign, or specific details.

If this supposed “Ethiopic War” did exist, and the Casluhim were in the northern extremities of the border between Egypt and Nubia, then that does line up with Thutmose’s campaign. While this dating does roughly match the transition between Naphtuhim and Pathrusim, it’s not clear who these people Josephus refers to were prior to their destruction, nor who they were after obviously. Identification related to what Josephus is saying is thus difficult, but it does line up with the “Kasluhet” of Kom Ombos, certifying where he potentially got his story.

Turning our attention to the Kom Omdo, the important city was located inside the very first Nome of Egypt, known as Ta-Seti, translated to “Land of the Bow” for their skilled archers. Ta-Seti was actually the border region between Egypt and Nubia, with the name Ta-Seti being used to refer not simply to the frontier nome, but also to the entire land of Nubia proper.4 As a result, an alternative name for this nome was actually Ta Khentit, this time translated fittingly as “Frontierland” or “Borderland” .

The ‘capital’ of the Ta-Seti nome - known as a “Niwt”, or main city, in Egyptian - was actually the island of Elephantine. Today, Elephantine is part of the wider city of Aswan, which at the time were two separate, but interlinked centers of political and economic gravity. The most interesting fact about this island is actually the presence of a significant Jewish community sometime around the 500s BCE, communicating with Jewish groups all the way in Israel.5 Books have been written about this mysterious community and their strange religious affiliations with their own separate Temple, but this shows the relevance of this location in later periods. The causative reason for the community in Elephantine was probably its location so far from the periphery of the empire where refugees from the destruction of the temple probably would feel more safe as far from imperial Babylon as possible.6

Despite this island's international presence, the native residents of Ta-Seti were seen as ethnically distinct from their northern Egyptian counterparts such as the proto-Saidi. While there is no established identity, they appear to have spoken a Nilo-Saharan language which might place them more in a Cushite branch.7 However, the reality is that with this nomes integration into Egypt proper these people would have been considered “Egyptian” still, not Nubian, and various consorts that came from this region appear to not emphasize their ethnic origin as significantly different from anyone else in the country.

Probably sometime during the aforementioned Ethiopic War, when Pharaoh Thutmose I pushed further south into Ta-Seti, all the way to the newly fortified city of Semna. After the conquest, Thutmose appointed the very first viceroy of Kush by the name of “Ture”, who actually went by the title “Sa-nisut-n-Kush”, which means something like “King's Son of Kush”.8 Very obviously Egypt viewed this region as Kush, but given the presence of Egyptians it’s not exactly clear the ethnic composition of all the residents, or if the Nubians were originally from here or simply settled further up the nile.

Turning to Rabbinic sources for a further hint, we have the Aramaic Targums - translations of the Torah into other languages for liturgical purposes - where the region of the Casluhim is called “Pentpolitai”, obviously derived from the Greek term “Pentapolis”. This term had various appellations but the only Pentapolis from Greek sources near Egypt was Cyrenaica, otherwise known as modern Libya, where five primary cities gave rise to the appellation “Penta” (five) “Polis” (cities). This is an odd name, and is clearly meant more as a colloquial designation to explain to the readers of the Targums who these people were, in a local context. Since most people were familiar with the pentapolis of Cyrenaica, readers probably assumed it referred to the native Libyans.

Linked to the Targums notion is Saadia Gaon’s own Judeo-Arabic translation of the Torah where he lists the Saidi people in place of the Casluhim, and the Libyians in the position of the Pathrusim.9 Some translations of the text actually reverse this order, making it impossible to say which one Saadia actually believed was correct, but the obvious correlation with the Libyians is quite supportive of the Targums theory, from where Saadia probably lifted this information. Given our own analysis of the Pathrusim agreed with the variant that places the Saidi people first, then the Casluhim would be the Libyians - if we were to simply agree with Saadia.

In a potential suggestion related to the Libyan theory, Islamic scholar Abu Bakr bin Yahya al-Suli identifies the Berbers - more than likely some tribe of them rather than the totality of them - as descendants of the Casluhim. We will see later who the Berbers are most likely identified as, but it is very possible Abu Bakr’s identification is a memory of some element of the Kasluhet who were destroyed in the Ethiopic War, merging into the Berbers we know today who live all over the Libyan territory. Its well known Greek and Latin texts permeated the Islamic world, so it’s possible Abu Bakr was merely closing the loop without any hard facts to go on after a section of the Berber group claimed descent from the Casluhim.

One reason for this blurred distinction probably comes from the ethnic nature of the people squashed between Egypt and Nubia. In a previous section we discussed the C-Group Culture, which mixes with the Kerma culture that encroaches upon its territory further south. The furthest site for the C-Group was actually the site of Semna, with the first cataphract providing the distinction point between Egypt, and this region we can call ‘pseudo Egypt’. This territory also saw intense settlement from the Medjay, as well as their potential cousins such as the Berbers whom Abu Bakr theorized were related to the Casluhim!

Clearly all of the links so far to the Casluhim have pushed them somewhere nearing classical Libyan, or Berber regions, but still placing them within the Nile given their relation to the other sons on the list. While later eras, this group might have lost their home and been forced to colonize new regions, or join with other tribes from Hamitic brother nations, during the period of primary Egyptian settlement between the 1900-1500s the territory would have been ethnically associated as a separate group from either Egyptians or Kushites. Let us wrap all of these theories up nicely by returning to my own theory of Dynastic Symmetry between the children of Mizraim and Egyptian broad dynastic periods.

We last identified the Pathrusim as the New Kingdom period of Egypt, associated with Memphisite rulers and the Saidi people, which aligns with the identification from Saadia. The period following the New Kingdom was the Third Intermediate, however, the distinction between the Third Intermediate and the following “Late Period” is negligible. Following the famed 1077 Bronze Age Collapse that ended the 20th Dynasty, the 21st dynasty arose around 1069, lasting roughly 126 year's. This was a native dynasty, yet still considered part of the intermediate period only due to the failure to unify “Egypt” as a single polity. Following the 21st dynasty saw the rise of the Meshwesh dynasty, a strange pseudo-Berber dynasty related to the foreign Libu people, whose name is notable for being the root of the term Libyan! Could these “Libyan/Berber” or Meshwesh Pharaohs provide the critical link for later identifications with Libyans and Berbers?

A complete and dedicated analysis for the Meshwesh will take place in the section on Put, but importantly this dynasty failed to unify Egypt, with a second Meshwesh lineage splitting and ruling in the south during the 223 year period in which these foreigners dominated the ‘native’ Egyptians. Dynasty 24 lasts only 12 year's and can be essentially excluded. The final dynasty of the Third Intermediate is the 25th under Nubian Pharaoh Piye. We discussed the Kushite rulers, and their early father Kashta of Nubia in previous sections, but essentially this provides a strong link to the southern piece of the Third Intermediate puzzle.

Many scholars attempt to split the Third Intermediate from this dynasty on due to the shift from ‘native’ rule by certain foreign dynasties, to a complete foreign dominion by external empires, with puppet rulers in their place. This puppet, or client state period of Egypt is typically termed Late Period, but I find no tangible distinction on an ethnic, or cultural level to be present. In fact, many of these Pharaohs from among the six later different dynasties are “Egyptian” in character, exerting their sovereignty distinct from foreign control. One major distinction is that the Third Intermediate Pharaohs line up with the Tanakh, while the closing of the canon is sometime during the start of the Late Period corresponding to the writing of Chronicles version of the Table of Nations.

The very obvious theory for why Philistines are left off the children of Mizraim’s list and only ‘begotten’ by the Casluhim could be more than ethnic, but the fact is these Philistines never once ruled any dynasty of Egypt. In a similar effect to the naming for the installed ruler of Kush being a “King’s son”, the Philistines might have also been a sort of “King’s son” installed as rulers over their five cities in gaza. Strangely, the Philistines themselves have a Pentapolis! How strange, both the Philistines and their ‘father’ the Casluhim are associated with Pentapoli, which might make this an important clue to understanding this lineage of Mizraim. Perhaps, the Casluhim, like the Philistines, had a system of five cities of governance that arose as a sort of cultural practice shared between their ethnicity? Until now, no one has found any cultural links between these people, but this could be a smoking gun if they share political systems.

Let’s do some digging, specifically etymological digging into the term “Casluhim”. Seemingly this term “כסלחים” (Casluhim) is foreign to Hebrew, as it doesn’t appear to be part of any notable roots. The real pronunciation is something closer to Cahsh, or Kahsh, eerily similar to the term “Kush”, possibly implying some connection as a border region? The next part of the term “LuCh” with the classic Hebrew Ch sound is the term “לח” with a connotation of dampness, humidity, or wetness. Combined with the -im suffix meaning ‘the sea’, we get something like “Kash-Damp-Sea people”. Could the ending part of the term be implying some technical aspect of the nile, potentially the cataphracts?

Many actually take the full term to be something like “fortified” although I regrettably cannot find a Rabbinic source for this translation. This translation is actually extremely critical to understanding these people, since it might link with the ‘five cities’ concept, since in Philistine culture these five cities were not just mere population centers, but specifically the Canaanite concept of a “fortified” or walled-city. If we were to view the Casluhim also have five, fortified, or walled military cities that may actually perfectly correspond to the Egyptian dominance over southern regions.

Interestingly, the concept of a fortress is only necessary on the frontier, and during the Pharaonic era both Lower and Upper egypt saw few, if any forts across a nearly 2500 year period. In contrast, Nubia had as many forts as both regions combined, and the Sinai had more than either region as well, not far from Gaza,, showing cultural continuity.

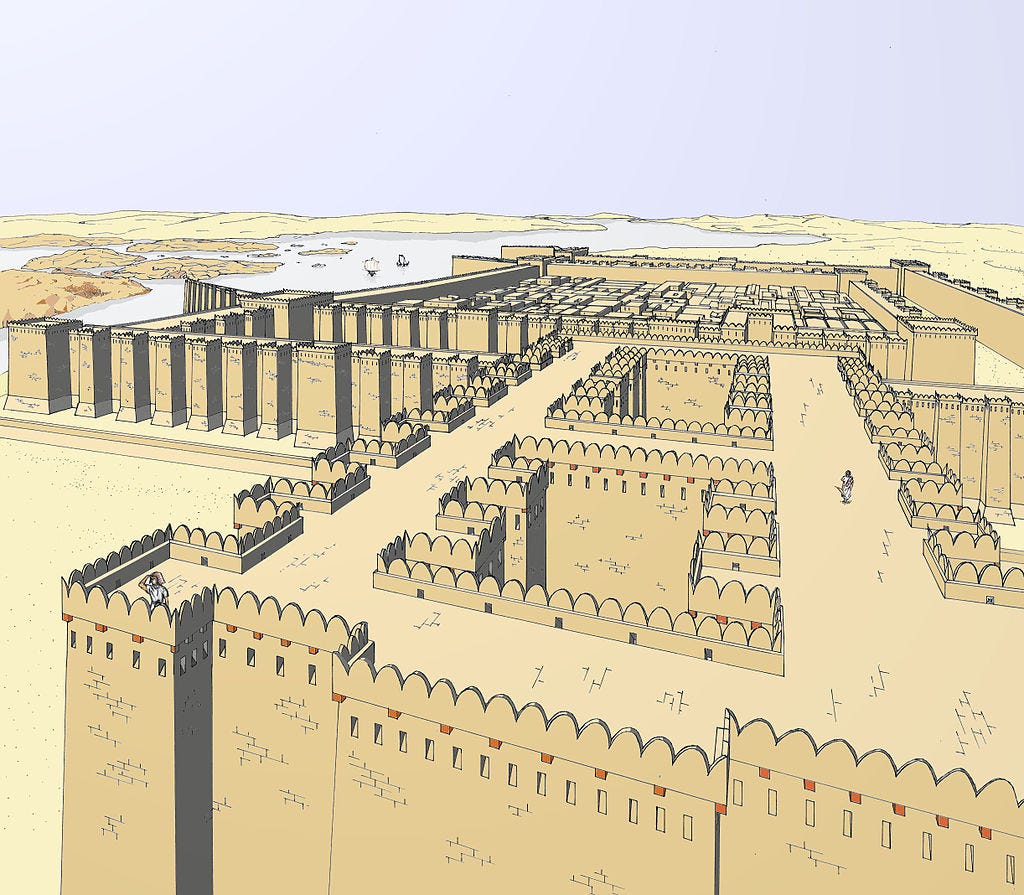

As previously established, the site of Elephantine/Aswan, as well as the city Kom Ombos which was itself called “Nbyt” (essentially Nubia) were located inside proper Egyptian territory, and were part of the southern most nome. Philae was essentially a religious island, and right within Elephantine’s control, but further south the similar religious site of Abu Simbel appears as an important site of Ramessid propaganda showing attempts to control this region. Next comes the critical city of Buhen which served as a massive fortress and military complex for the Egyptian army. Further south was the city of Mirgissa, known in the ancient period as Iken, which had a similar massive fortress complex to Buhen.

Finally, we reach the southernmost point of the Egyptian conquest in Semna, which likewise had another major fort system that developed within the city. This fort is pictured below. In fact, within the nearby area of Semna a cluster of four forts were constructed. It’s very possible there was a fifth fort, and Semna itself was the location of a sort of Pentapolis. All of these forts are now under Lake Nassar thanks to the Aswan Dam project.

While I cannot find the exact source, there is a seemingly related term that is considered a “surname” for the Casluhim known as “אוּסְמָנָא” (Ousimana), or “the glistening”. This would correspond to something like a title for the people, based more on their achievements, or historical activity rather than with their personal ethnic character. How this term relates is unclear, but there could be some connection to the concept of “fortification”. Why? If we go along extremely tenuous logic, the concept of a glistening is chiefly, what? A ‘shining’ of something until it sparkles with light. The ‘shining’ of the cities would indeed be a ‘fortification’ of already founded cities, with the walls being something like the sparks that emanate from the now radiant cities. This is the only way I seemingly can connect this term conceptually.

There is another strange etymological link that may not actually provide clues, but is helpful to look at regardless. Just like the Hebrew God goes by many names, the Greeks also held many names for Zeus, one of them being “Zeus Kasios”, or in Latin Casius. Two competing sources of origin for this name are hypothesized: the first coming from Mount Kasios in Jebel Aqra on the Syrian-Turkish border, and the other from the site of Casion near Pelusium in the Delta of Egypt.

The former name seems less likely because it appears as a later Greek hellenization with the Canaanite weather God Baal Zephon, who served like the Canaanite version of Zeus who was synthesized in later eras. While at first this seems tangential, Mount Kasios is known in Hebrew as Mount Zaphon צפון from the Book of Isaiah.10 This city's critical link to the major regional capital of Ugarit places it at the center of the Baal Cycle within Canaanite mythology, verifying its importance from an ancient lens and making this theory more likely, than not.

The latter theory is quite compelling, still, since it does link into Egypt regardless of the actual origin for the term from Mount Kasios. This Casion in Egypt though was similarly a shrine to Zeus, and is today known by the etymologically derivative Arabic name “Ras Kasaroun”. The Egyptian site, like the Canaanite Mount Kasios that was hellenized into a site of worship for Zeus, this site was also originally a worship location for Baal Zephon syncretized by later Greek settlers.

Near this site was the fabled “Serbonian Bog” which was the location of Zeus’s rival Typhon, and a seemingly miserable location for a city. Ptolemy tells us the name of multiple towns in the vicinity, and shows there was capable of a significant population in the region during an earlier period, enough to support some kind of tribe.11 The most important city in relation to this Serbonian Bog was the closest Egyptian city, and boundary of what was called “Egypt” in the ancient world, the city of Pelusium.

According to Pliny, who says “At Ras Straki, 65 miles from Pelusium, is the frontier of Arabia. Then begins Idumaea, and Palestine at the point where the Serbonian Lake comes into view. This lake... is now an inconsiderable fen.” Here, Idumaea means Edom, and the territory of the Edomites around Sinai, while Palestine refers to Israel, and Philistia combined since Pliny was writing during the Roman era when the province was called Palestina. The lake itself was the actual boundary between Canaan and Egypt, with the regional site of Pelusium, and the settled sites of the Philistine Gaza cities being central to the politics of the territory.

Whatever the case with this site, it is obvious it has Canaanite origins, and later Greek populations, linking both Casios together as potential colonies of some population of the Casluhim. The reasoning and link for this Canaanite-Greek connection will become clear soon, but discussing the Casluhim is impossible without also discussing theories of the Philistines who are some to have been “begot” by the Casluhim.

Archibald Henry Sayce (2009). The "Higher Criticism" and the Verdict of the Monuments. General Books LLC. p. 91. ISBN 978-1-150-17885-6.

Steindorff, George; and Seele, Keith. When Egypt Ruled the East. p. 35. University of Chicago, 1942

Breasted, James Henry. Ancient Records of Egypt, Vol. II p. 50. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1906

Newton, Steven H. (1993). "An Updated Working Chronology of Predynastic and Archaic Kemet". Journal of Black Studies. 23 (3): 403–415.

Botta, Alejandro (2009). The Aramaic and Egyptian Legal Traditions at Elephantine: An Egyptological Approach. T&T Clark. pp. 15–116. ISBN 978-0567045331.

A. van Hoonacker, Une Communauté Judéo-Araméenne à Éléphantine, en Egypte, aux vi et v siècles avant J.-C, London 1915 cited, Arnold Toynbee, A Study of History, vol.5, (1939) 1964 p125 n.1

Christopher Ehret, The Civilizations of Africa: A History to 1800, University Press of Virginia, 2002.

Breasted (1906) p.27

Saadia Gaon (1984). Yosef Qafih (ed.). Rabbi Saadia Gaon's Commentaries on the Pentateuch (in Hebrew) (4 ed.). Jerusalem: Mossad Harav Kook. p. 33 (note 37).

"Zaphon", Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible, 2nd ed., Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 1999, pp. 927–928

Geography 4:5, 12; comp. Josephus War, 4:5, 11

This is outstanding and very comprehensive.