Ashkenaz

Shifting Homeland of the Germanic Migrations

Gomer had three sons. The first being Ashkenaz, whose name is well known for becoming the moniker of “North European” (Non-Mediterranean) ‘Ashkenazi’ Jews. As the name implies, Ashkenaz has morphed over the centuries and not always been identified as the same regions.

In keeping with this methodology, early periods identified them around Scythian territory, more-or-less identical with Gomer and the Cimmerian’s land. This Scythian-Siberian cultural zone would play a major role in the foreign policy of any nation bordering with traditions from Rome, Persia, and China all identifying Huns, Turks, and Mongols as major border rivals. However the term continued to shift and be applied to regions near the Scythian territory, or bordering it, and not directly correlating to the Scythians. Whether intended, or not, this fits well with the picture of Ashkenaz’s descendants being a sub-tribe of Gomer, himself a sub-tribe of Scythians, making Ashkenaz a Sub-Sub-Tribe of the Scythians themselves and closely related.

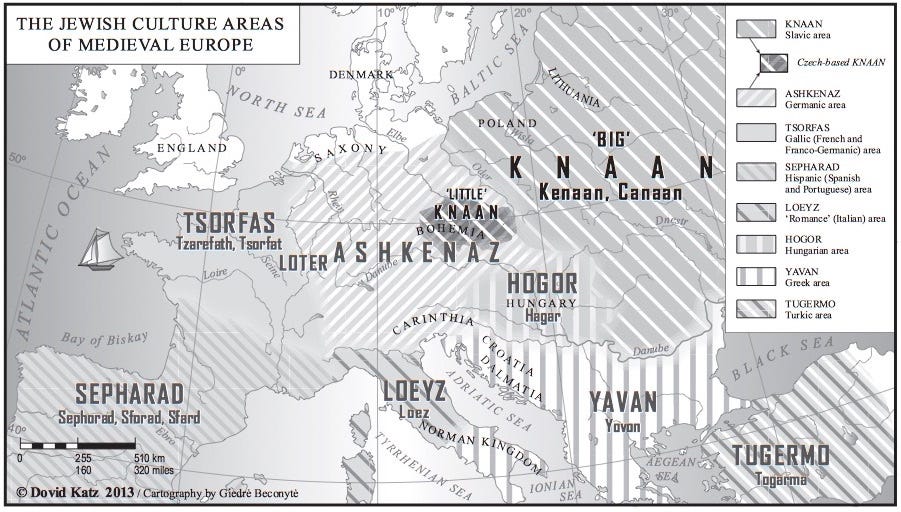

The association for Ashkenaz became broadly ‘Slavic’ prior to the 8th century, again fitting well with a territory bordering Scythia, and eventually being applied in the 11th century as far as northern France, centered on the German Rhineland. It should be noted that despite “Ashkenazi Jews” coming from Russia frequently, in later periods “Ashkenaz” was not properly recognized to include Slavic lands, or Russia and had shifted west. This rabbinic shifting of homeland for the Ashkenaz fits directly with the Germanic migration patterns in traditional scholarship that we will now discuss.

Briefly diverging, we should discuss the precedent for how these terms would be reappropriated from their original definitions, oftentimes without correlation. In Hebrew the term for France is “Tzarfat”, a name given to a small city in Lebanon in the biblical period. Later Rabbis co-opted this term and applied it to France owing to the way in which the word backwards spells out the name France in Hebrew. France is spelled “F-r-ts” and Tzarfat is spelled “Ts-r-f”, showing clearly that Rabbi’s would often erroneously apply names to different regions. Another example of this is the term Safardi, coming from the term “Sfard”, which was the Hebrew term for the Kingdom of Lydia later applied to Spain. This will again become relevant when we deal with an identification for these Lydians, but for now what this shows is that Ashkenaz as an ethnic geographic term for Jews doesn’t necessarily correlate to “Ashkenaz” the biblical figure.

Note that on the above map, these terms are all Medieval applications and not terms used in the classical or ancient eras.

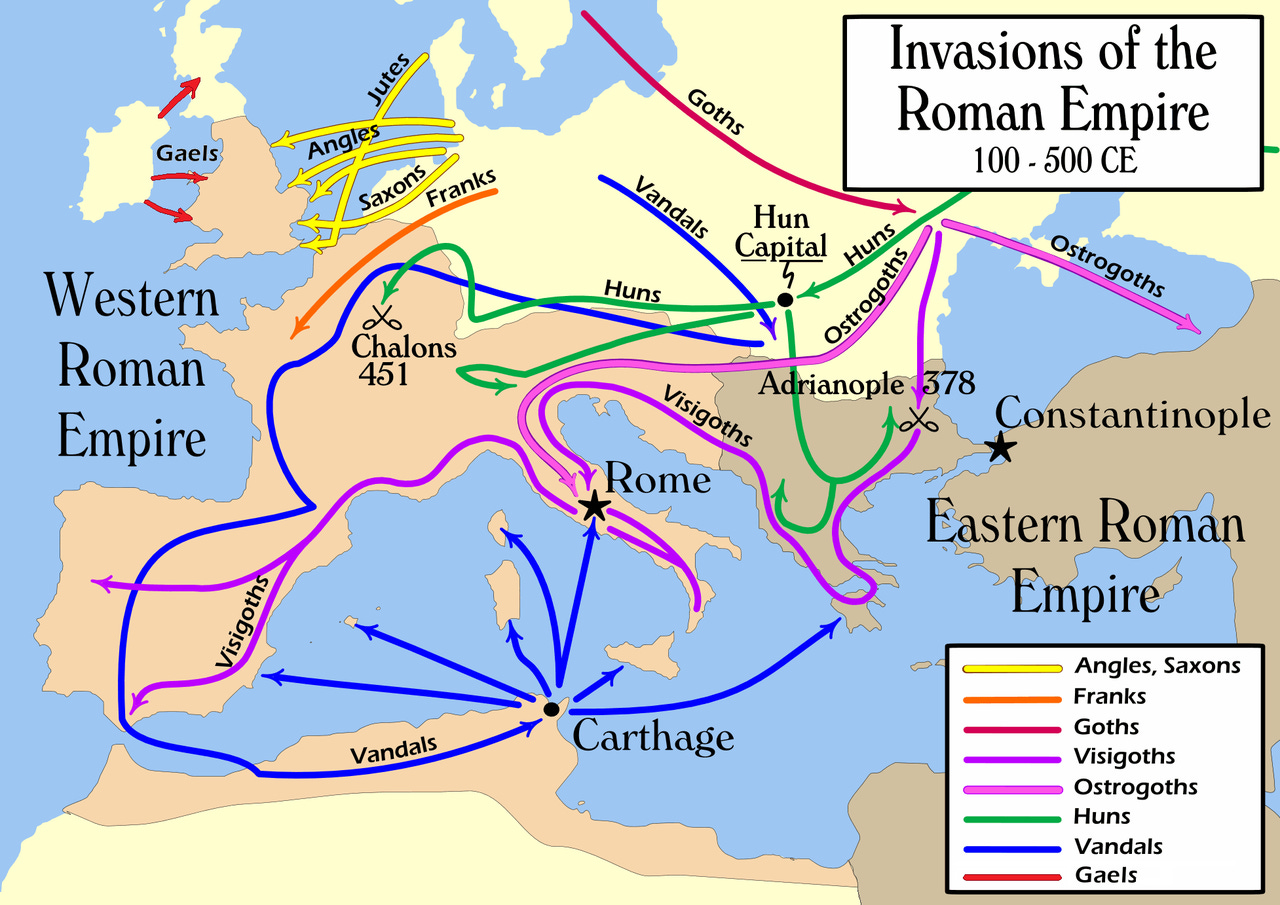

From as early as 1000 BCE all the way through the 8th century CE a “Migration Period” saw the movement of continuous waves of Germanic peoples migrating throughout Europe - and often beyond to Africa, or the Mid East as in the case of the Vandals or Varangian Guard. Colloquially called “Barbarian Invasions” in popular culture, these mostly violent invasions peaked during the “Fall of Rome” between the 3rd and 6th centuries. The actual “ethnicities” or tribes making up these people are as diverse as Angles, Saxons, Huns, Franks, Alans, Alemanni, Jutes, Frisii, Burgundians, Suebi, Lombards, Normans, Goths, Vandals, early Slavs, Magyars, Bulgars and one could tenuous group the later Viking invasions into this period. Not all of these people are classified as Germanic, but many of the nations these people settle have large Germanic ancestry.

Important to note is that “Germanic” doesn’t necessarily mean “German”, but would include modern France, Belgium, Netherlands, Switzerland, Germany, Scandinavia, England, Austria, North Italy and large parts of Spain and Czecky. Groups such as the Franks lent their name to the word “France”, and the “Angles” is the origin for the term “Engle-land” otherwise known as England. Many local place names, and cities come from the various tribes and sub-groups within these people - regions such as “Lombardy” in Italy coming from the eponymous “Lombards”, Burgundians known from the Bourgogne wine region in France, Frisians in the Netherlands having their own language and subregion - but a full list would essentially require telling the entirety of European history. While the ethnic makeup of these modern european nations is more complex than “Germanic”, the listed nations contain a significant admixture and many of the cultural substrates that form the backbone of these nations traditions which are definitely “Germanic” in origin.

These later migrations occur contiguous with the time of Rome, but the earliest expansion waves out of Scandinavia occur during the Bronze, not Iron age. We will see over coming sections how Iron Age identifications typically align with post-Mosaic nations often referenced in the Prophets, Judges and Kings era, while Bronze Age identifications align with the earliest listing of the Table of Nations at the onset of genesis. This listing coming prior to Moses, prior to even Abraham, implies that individuals such as Japheth, Gomer, and Ashkenaz lived at a time earlier than Abraham’s birth. Importantly, there are no individuals mentioned in the genealogy other than the odd man out Nimrod who lived during Abraham’s era. This would imply all of these figures had already lived and died well before Abraham’s time, and may even imply there were two separate Nimrods. This theory of “two Nimrods” and the historical conflation of both potential Nimrods will be explored during a discussion of Ham’s children. Let us turn our attention to reconstructing the migrations of the Germanic peoples and explore their Bronze Age origins.

Based on the Proto-Germanic Sprachbund and correlating archeological sites, the Urheimat (homeland) of the Germanic peoples was Scandinavia and North Germany between 1500-500 BCE.1 This essentially equates to Norway, Denmark, and Sweden, and implies a tradition of Scandinavian seafaring migration goes back much further than the “Viking” era. The principal territory of these Proto-Germanics were the Scandinavian peninsulas, but was bounded in the south between the Elbe and Oder rivers. Eventually successive waves of Germans began colonizing these river basins, crossing over into the Weser, Ems, Vistula, and Rhine rivers while continually pushing into those basins.

During the Iron Age, roughly between the year's 600-100 BCE, these Germanics began shifting further south into the La Tene cultural horizon. The La Tene were Celts and close contact and intermingling - especially marriage - is attested to both in Celtic loanwords in German and the genetic flow between skeletal remains of these populations.2 This initial wave was likely enabled by the movement of Celtic peoples further south, leaving a demographic vacuum around the Danube and Rhine.

The academic name for this cultural region is the “Jastorf Culture” and represents the pre-celtic contact Germanic groups of Europe. This area contiguous to the Jastorf culture is where most Germanacists agree a strictly “German” - IE, excluding Scandinavian, or Norse - Urheimat would be centered around.3 Many of these “Germanic” groups would culturally shift into Celtic, oftentimes speaking Celtic while retaining Germanic undertones and ethnicities. Due to the inability of ancient writers to differentiate specifically “Celtic” or “Germanic” cultures in this period, and the genetic drift between populations, it becomes challenging to identify which category tribes in this era fall under.

By the first century AD Germanic speakers had reached the Danube and Rhine beginning their first entrance into the historical record. In this period we see Germanic loanwords start shifting into Proto-Slavic, as well as the aforementioned increase in gene flow. Oftentimes both Western and Eastern Europeans share R1a and R1b genetics between each other, in varying levels of proportion, with these Germanic migrations forming the basis for this shared admixture among modern populations. These mixed Germano-Slavic populations continually made their way west through the 5th-10th centuries, further integrating with modern “Germanic” descendants and complicating an exact ethnic background for modern europeans.

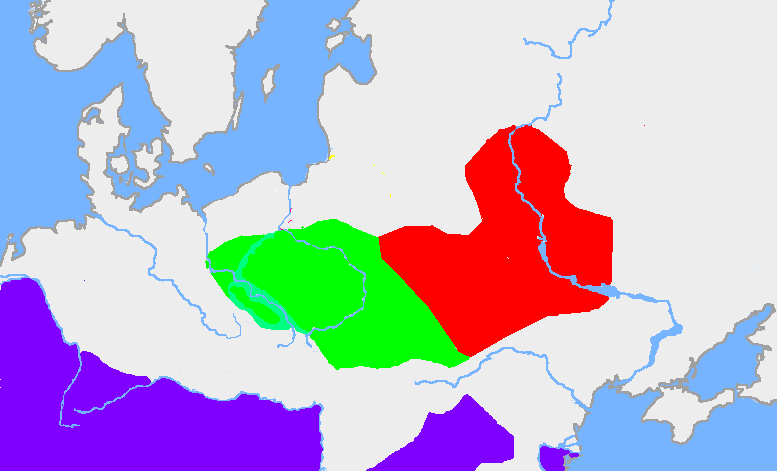

This mixed population of German/Celtic forms what is referred to as the Przeworsk culture that spreads across much of Poland, into modern Ukraine as far as the Dniester river. Accordingly these populations interacted extensively with Proto-Slavs in the region, with the closely related neighbors of the Zarubintsy culture showing many similarities to the Przeworsk albeit with a higher admixture of Scythian and Sarmatians than either Celt or German. On the attached map the red area represents Zarubintsy settlement, the green are Przeworsk, and purple is the Roman Empire. As the Empire dissolves, the Przeworsk group migrates over the Carpathian mountains and settles along the Danube River, the major northern border for the Romans.

Helpful for our purposes is the first ‘coherent’ recorded text in Germanic, the Gothic Bible, written around the 4th century. Preserving many translations for the new testament and some old into the German language, this Bible is incredibly important for linguistic scholars in understanding the evolution of the German language and culture. The specific language is Gothic, but even more specifically a sub-branch of Gothic spoken by the Thervingi Goths who had converted to Christianity.

The Thervingi had migrated to the border of Rome after pressure from the well known Huns of Attila pressed them to the east. These Thervingi were arguably the most important Early Germanic ‘Barbarian’ tribe on the Roman frontier. Originally settled on the south bank of the Danube through a negotiation between Roman Emperor Valens and Thervingi leader Fritigern; this deal fell through after a famine in the region broke out and Rome refused to supply the Germans with promised food supplies. This spiraled out of control into the “Gothic War”, which climaxed at the Battle of Adrianople in 378 CE where nearly the entire Roman army was slaughtered, Emperor Valens was killed, and six years of plundering the Balkans near the capital of the Empire raged. While the Roman Empire was far from over, many mark this era as the seismic shift in Roman politics that sealed their eventual fate.

These facts are not critical for our endeavors, but what is necessary to mention are that these Thervingi reportedly escaped from Scythia and moved to Moesia before this ensued around 348 CE. Their movement from Scythia helps provide a strong connection between “Germans” and “Scythians”, and gives us context for how ancient writers would have seen these people. Shared linguistic, genetic, and cultural fluidity of these people was nonetheless different enough that ancient writers felt a need to separate “Germans” into an “Ashkenaz” group.

This also explains why in the 5th century, “Ashkenaz” were still associated with these Thervingi regions around southern Ukraine rather than anywhere near Germany despite migrations having taken place from Germany originally. In many ways, the later identification of Ashkenaz around the French-German border region strongly characterized by early waves of European Jewry was a return to a more accurate regional description for the Ashkenaz. However, we know this identification with Ashkenaz and the Scythians comes from the post-classical era at the turn of the medieval period and would suggest there might be an even earlier period when Ashkenaz and Scythia correlated.

Tracing German migrations back across the Danube, over the Carpathian mountains, through Poland down the Vistula river, towards the Elbe, and back through Scandinavia all the way past 1500 BCE we arrive at what is termed the “Nordic Bronze Age”. While not technically “German” in character - a later identity that forms for the Jastorf sub-group of Nords - these Proto-Germanic Nords are the progenitors of what would become Germanic, and more closely date to the period the Table of Nations is describing during the turn of the Bronze Age. While elements in North Germany break off and migrate out of the region, the tribes in the area continually develop into what we know as the Norse, responsible for the Viking Age. Major Germanic tribes such as the Goths originate from this region, and merge their Norse identity into something more “German” showing a close similarity between these two cultural traditions and ethnic subgroups.

While one might think Scandinavia would be quite isolated from the rest of the international community, goods such as Amber and particularly metals were imported on a massive scale. Surprisingly these metals came from islands as far as Sardinia and Cyprus showing an extremely well connected network of trade routes during the Bronze Age.4 While this network of trade was disturbed during the Bronze Age Collapse it was quickly restored, and it’s unlikely ancient writers would be unaware of major groups in Northern Europe.

Importantly, it wasn’t just the goods being traded but the cultural connections clearly began influencing Norse culture, evidenced by a so-called “Mycenaean Package” - a series of cultural styles and shared traditions. Included in this package were flat-hilted swords, usage of campstools, extensive solar imagery, spiral decorations, and particularly tools for body care such as razors and tweezers.5 The latter of these help provide early evidence for the emerging complex hair styles, and beard styles that are well known to both Germanic, Celtic, and even Italic groups. We know from the importance of Jewish beard styles, and the avoidance of cutting the four corners of the beard, that shared beard traditions were actually critical to a culture.

Even more important were shared institutions based around warrior culture with power split between a “Wanax” and “Lawagetas” nearly identical to Mycenae. This “co-kingship” was clearly passed down onto the Spartan traditions, helping show some early continuity between Germans and Greeks during the Bronze Age. It is unclear if these traditions were from Mycenaean spreading into Scandinavia, or if these stemmed from an even earlier Indo-European core that would also explain the shared cosmological symbolism and solar art.

Beyond their contacts with Greece, the Nordic Bronze also maintained close contact with the nearby Hittites in Anatolia. Evidence for the transmission of horses, and chariotry, as well as common symbols such as the one for “divine” showing up in Scandinavia helps provide further support that Germans were well intertwined with the ancient world. There is even evidence for contact with the New Kingdom in Egypt.6

A little about the origin of the term “Scythian” is useful to understand how the term morphed into Ashkenaz. The English word comes from the Greek name for these people “Skuthoi”, itself coming from the Scythian endonym for their people “Skuoata”.7 As previously discussed the term came from the Indo-European root for “shoot”, and may have meant something similar to “archer” helping show an association between the Scythians and skilled warriors with a bow. Ultimately it is not war where a bow is most useful, but rather during hunting, and it was dominant hunters able to provide the most food for their tribe that out competed and thus out populated rival cultural groups. According to Herodotus this term was actually the designation for the “Royal Scyths” aristocratic sub tribe rather than the entire nation, and it was through these elite nobles that the “Germanic” culture spread.

The Nordic Bronze itself was an outcropping of the much earlier Corded Ware culture, itself stemming from the previously mentioned Yamnaya culture. It is the interaction between the Corded Ware and Yamnaya that births the ethnogenesis of the Nords, and Germanic peoples, with many of them “converting” into the cultural traditions that begin to dominate and spread by a warrior elite, themselves called “Ashkuzai”. This would clearly put Ashkenaz as some sort of hero leader of the “Germanic/Alemanian” peoples, all who extend from one common “Gomerian” ancestry coming from a shared Indo-European Yamnaya steppe homeland.

Once again thank you for reading this weeks post and I sincerely hope you could gain value from reading. The subject matter can be quiet dense and challenging, so don’t be afraid to leave a comment and ask me anything additional to help round out a piece of the puzzle.

Also feel free to leave an ideas for additional posts, or subject material. I’d be glad to break up the weekly Table of Nations writing for either another subject inside Torah and Tanach, or even broader Talmudic and Judaic studies. I’d even love to write something on a political subject, or how some of these historical ideas connect to the modern world, but I will leave that for brainstorming.

Ringe, Donald (2006). From Proto-Indo-European to Proto-Germanic. Oxford University Press. P. 85. ISBN 0-19-928413-X.

Ringe 2006, p. 296

Mallory, J.P. (1989), In Search of the Indo-Europeans, Thames and Hudson p. 89.

Kristiansen, Kristian; Suchowska-Ducke, Paulina (December 2015). "Connected Histories: the Dynamics of Bronze Age Interaction and Trade 1500–1100 bc". Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society. Cambridge University Press. 81: 361–392.

Kristiansen, Kristian; Larsson, Thomas B. (2005). The Rise of Bronze Age Society. Cambridge University Press. p. 249.

Varberg, Jeanette (2014). "Between Egypt, Mesopotamia and Scandinavia: Late Bronze Age glassbeads found in Denmark". Journal of Archaeological Science. 54: 168–181

Ivantchik, Askold (April 25, 2018). "Scythians"