Previously, when discussing Meshech, we mentioned a Thyragetae in connection to the Getae, or Geto-Dacians. More accurately, these Thyragetae are Getae of Thyras, otherwise known as Tyras. This Tyras was a Greek colony founded by settlers from Miletus around the 6th century BCE at what is now the mouth of the Dniester river. Tyras was not named after the local Thyragetae, but rather both the city and tribe take their name from the river Dniester, known also to the Greeks as Tyras. According to Greek writers, these Thyragetae were actually immigrant Sarmatians, implying that both the Getae and these people were Sarmatians. However, we know from ancient sources that the Getae and Sarmatians were enemies and often fought battles against one another, meaning they definitely didn’t consider each other the same political coalition.

When looking at the Dniester, or River Tyras in Greek sources, it would be important to note that in the 7th century the only reason for a Greek colony on the mouth of the river would be lucrative trade upstream for them to exploit. If there were no tribes upstream, then the river would have no value, and while the Getae did live near the mouth of the river, there is no indication they lived much further inland. If the river of the “Tyras Getae” are to be believed, the name is from an earlier Indo-European peoples.

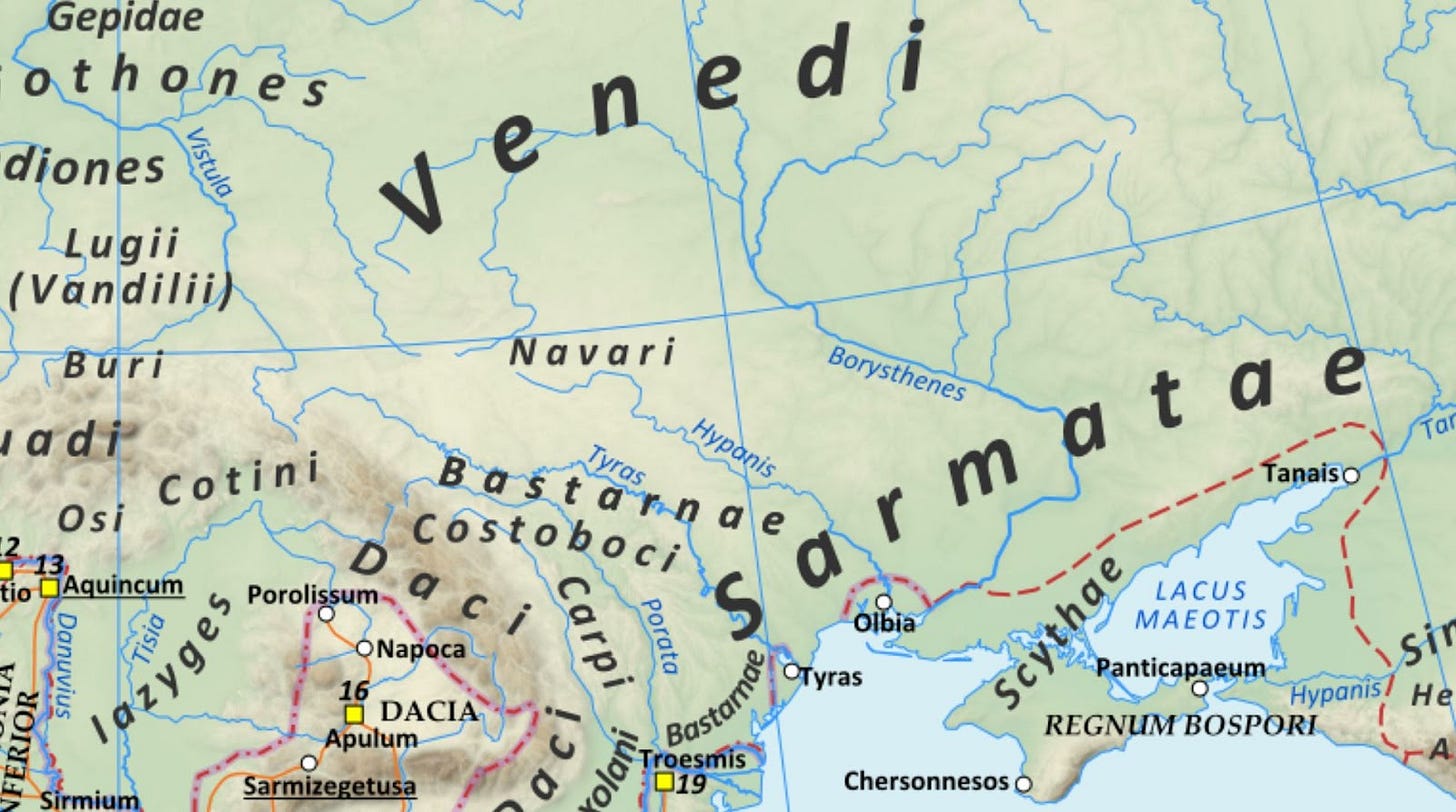

Further up the river we do find both the Costoboci and Bastarnae between the Carpathian mountains and the Dniester. Both of these tribes are likely pseudo-Celts, living similar lifestyles to their Dacians and Sarmatian brothers, but beginning to form the ethnogenesis of what could be called “Celtic”. Evidently, their material culture lines up with the spread of Celtic from the west, and the areas most east normally identified as Celtic settlements. Furthermore, a confirmed Gaulish, aka Celtic, tribe named the “Cotini” were directly west of both of these peoples, showing further Celtic similarity. Either way, both of these tribes were still essentially Dacian, and wouldn’t necessarily constitute their own national polity, especially not in the Bronze Age, and even by the 1st century AD during the Roman empire still barely unique.

Interesting to include is the fact the “Carpi” tribe was centered around the Carpathian mountains. This tribe's name, like the Carpathians, comes from the Indo-European root for mountain, or large rock.1 This tribe is nearly confirmed to be a Dacian tribe based on the etymology of the term “Karpodakai” - meaning “Dacians of the Carpi (mountains) - being similar to the term ‘Thyragetae’ - or Getae of Tyras. The origin for the term Carpathian is unimportant for our purposes, but it does show that the “Dacians of the Carpathians” were these Carpi, implying that the Costoboci and Bastarnae are not fully Dacians.

Important to note is that the Dniester did indeed form the border between Dacia and Sarmatia. Even the name “Danu-Ister” implies a Scytho-Thracian origin as the word “Danu” means river in Scythian, and “Ister” being Dacian, notably from the city “Istria”, another Dacian city further down the coast. Possibly, the right side of the river were Sarmatians, and the left side were Dacians, up to the Danube, at which point “Thracians” proper would begin.

Looking at a map of the region around the time of Rome, we can see the river Tyras was inhabited by Bastarnae, Costoboci, Sarmatians, and the aforementioned Getae - with a small Greek population on the coast. However there is one other tribe that negotiated a settlement agreement with the Sarmatians, called the Navari, or “Neuri”. According to Herodotus, the Neuri and Sarmatians agreed to a border along the Tyras river2 as well as saying that the Neuri “Follow Scythian customs” whatever that means exactly.3 These Neuri were not originally from Tyras though, being driven from their land due to a snake infestation, and thus forced to settle among the Budini. Modern consensus has arrived on these Neuri, or Navari, as a proto-Baltic peoples due to a variety of factors.4 Chiefly, the fact that Baltic mythology centers around worship of a grass snake helps correlate to the story of the snake infestation, but also the Narew river in Poland is known as the Naura river in Baltic, a region originally inhabited by Balts. It can thus be said that these “Neuri” are the sons of Scythians, or Sarmatians, and could constitute some type of grandson, or perhaps great-grandson of Japheth, and like Danaus potentially an “additional” son on the Table. This name may be familiar to readers as it’s quite similar to the “Nairi” mentioned previously who may have been related to Armenians.

Mentioned alongside the Balts are the Budini, where the Nauri are said to have taken refuge after their flight from the great snake infestation. Due to the location of the Narew in Poland, it would therefore be presumed that this Budini homeland is located in the same region. Indeed, scholars such as Boris Rybakov and Boris Grakov posit a proto-Slavic connection for the Budini, and together with the proto-Balts of the Nauri would certainly represent the combined Proto-Balto-Slavic family.5 The area of the Budini is presumed to be quite large, confirming a mostly Slavic ethnogenesis. Additionally, in classical sources the Budini are associated with reindeer, further implying dominion over the great boreal forests of the tundra. Like the Neuri, it’s possible the Budini are another “great-grandson” or Japheth, as the Torah doesn’t intend on providing a complete lineage past a certain point.

Slightly more north on the coast of the Baltic Sea, located around the Vistula Lagoon were the Aesti. Their name is connected to Lithuanian names for the Vistula Lagoon, called “Aistinmari” in the native tongue. Linked to the Aestii is the name for the country of Estonia, getting its name from this tribe. Also located along the Vistula, dominating a large territory similarly, or mostly contiguous with the Budini, were the Venedi. Based on the oldest Slavic hydronyms6, the origin for the Slavs would be located somewhere between the Middle Dnieper and the Bug rivers, expanding North, Northeast and Northwest with the proto-Balts. It should be mentioned that “Slavic” is a much, much later designation and no such group shows up until the 6th century AD, some 1500 year's after the Bronze Age. These Venedi, or Budini during the Late Bronze Age would hardly constitute a separate people group.

The final, and perhaps most obvious group, was the “Fenni”, known to the world as the Finns. Like the Balts and Slavs whom Tacitus distinctly identifies as separate from both Germans, Celts, and Scythians, these Fenni are also clearly distinguished from the Aestii and Veneti.7 Tacitus doesn’t describe a single Fenni group, but rather two distinct groups, with one being located north of the Scandinavians, clearly indicating these are the Sami peoples. The other group, east of the Vistula, would be modern Finns proper. Both of these groups are part of a wider Finno-Ugric grouping.

While none of these peoples contain any possible links to Tyras, other than having been located on, or north of, the river, the etymological origin of Tyras, and any other Tyras, might possibly have been due to a group coming from the Tyras river, even if they did not settle along that river permanently. However, it is helpful to understand the wider geographic context of the region, and rule out a northerly location for Tiras. This is not the end of our search, as there are two other major groups potentially linked to Tiras: Persia and Etruscia.

When discussing Madai we associated them with the Medes or Iran. Given that the Persians - as well as the later Parthians - all descend from the same West Iranian, Old Persian speaking people, it is safe to assume that all three of these groups are fairly similar. None of the six tribes of the Magi, nor the ‘Seven Great Houses of Parthia’ have any tribe remotely similar to a “Tiras”. Interestingly the most modern descendants of these two people are likely the Kurds, who are a fusion of these two cultures, and languages. Given that the Kurds have never claimed any descent from Tiras, but do have traditions of descent from Madai, it’s fairly clear these people are identified with Madai. Persia, and Parsis, only extend from their collective identity as “Old Iranians”, and it is not until the 5th century any of these identities separate (Persian, Parthian, Medes).

It would also be strange if such an important nation in Jewish history, being associated with Tiras, wouldn’t have some sort of prophecies to go along with Tiras. Instead, we find in Ezekiel 27:10 “פָּרַ֨ס”, or “Paras” in Hebrew, named and certified as Persians. While one of traditional rabbinic identifications for Tiras is with Persia, that is based on etymological links, and nothing more. Thus we must briefly dispel the etymological inaccuracies.

Tiras in Hebrew is “תִירָֽס” which at first shares the final two letters with Paras, but lacks more than just the “T” sound. In Hebrew, the “P” letter can become “F”, which lines up with the “Pars>Fars” shift inside Persian. T on the other hand seemingly comes from nowhere, and the Yud apparently disappears. The “Yud” indicates that “Tiras” is pronounced “Tyras” rather than “Tie-ras”. Furthermore, by the time of the rabbis, the vowel sound “Ah” in Hebrew had lost its slight nuance. While the full vowel in Tiras representing “Ah” has a T shape, the actual vowel shaped like a ‘-’ in Paras is not a ‘long ah’ sound, but a much shorter ‘ah’, functioning slightly silent, getting the word “Paras” pronounced closer to “Pars”. None of these sounds are shared between Paras and Tiras, and a mere etymological link, no matter how great the sage is, is not enough to identify Persia with Tiras. Besides the fact all of these so called “Iranian” peoples only begin their ethnogenesis after the 10th century BCE, making their identification of the direct son unlikely.

Let us turn then to the final potential link, and indeed arguably the only remaining ‘people’ group in Europe unaccounted for; the Etruscans. While most academics tend to use linguistics as some indication of a peoples “ancient” origin, this is nothing but speculation and pure theorizing. No one knows what the “native Etruscans” spoke in the year 2000 BCE, nor the Basques, pre-Nuragics, or even the Iberians. Based on the genetic information of all four of these groups, they are all R1 Haplogroup, indicating identical gene flow between these populations and the rest of europe, and thus being tribally, and ethnically Indo-European. How these languages were adopted is unclear, but it is possible that the Basque and Etruscan languages were remnants of the leftover Solutrean and Gravettian cultures that survived in the Last Glacial Maximum Refugia.8 How their language comes to be is for the story of Babel, which recalls the confounding of languages.

Importantly, all of these populations only spring up after the year 2000 BCE, with cultures such as the Terramare showing up around 1800. Regarding these “Terramarians”, there is a story related by Dionysus of Halicarnassus in his first book on Roman Antiquities relating to the Terramare culture of the Po river valley in Italy. According to Dionysus, until two generations before the Trojan war, circa 1200 BCE lining up with the collapse of the Terramare in 1200 BCE, there were a group of Pelasgians that occupied the Po valley. According to Dionysus, these Pelasgians move south after a series of famines, and end up blending in with the native aborigines, possibly Etruscan speakers.9

Traditional academia discounts this story, but the archeological evidence of this group's collapse, and the Terramares shift southward into Etruscia is now a well documented occurrence. In Greek culture, Pelasgians are Indo-europeans but represent the Barbarian component of a region, lining up with the Terramare who are also Indo-European ethnically, related to the various waves of Indo-European settlement migrations. We can then assume, as traditionally was, that the term Pelasgian refers to the populations, or ethnicities, that eventually collapse into more certified nations post Bronze Age. The pre-Greek Pelasgians of Mycenae, the Pelasgians of Crete (Minoans), as well as the Etruscans, a group only attested to after the 8th century, being all claimed to descend “from Pelasgians” and inhabit traditional Pelasgoi lands.

If we are to assume Pelasgoi is a broad cultural class to refer to Barbarian Indo-European groups, then there must have been a wave of settlement when these groups migrated. Indeed, nearly all of western and central europe were colonized by a wave of Indo-Europeans showing similar cultural stratum, and we will deviate for a moment in order to analyze migration patterns coming out of the Yamnaya heartlands.

Clear in this first chart is that from the Yamnaya steppe region, a branch of Yamnaya spread along the Danube, with another branch splitting offer and forming the “Corded Ware” culture, that also feeds into the later Sintashta culture, which fuses with Yamnaya to form it’s more eastern elements such as the Andronovo culture, which goes on to form the majority of the “Iranian”, or Aryan groups discussed during Magog and Madai. All of this is happening between 4000-3000 BCE.

The next period we come to is when these cultures begin to diffuse across Europe after the year 3000 BCE. We can see the western Yamnaya branch spreads out around 2800, clearly indicating an ethnic origin for the R1b “Western Europeans”, with Corded Ware being an early Germanic, and the Eastern Europeans continuing their complex ethnogenesis in the steppe as Yamnaya. By the Late Chalcolithic, these R1b Bell Beakers dominated the entirety of modern Western European borders, with many disparate remnants in the Greek world. Based on archeological evidence and ancient assumptions, it’s clear that “Pelasgoi” is a term to refer to these earlier waves of Yamnaya. Indeed we find that the pre-Bell Beakers, or pre-Indo Europeans such as the Polada and Remedello cultures of the Po Valley actually constitute Haplogroup G and I respectively. G is associated with Early European Farmers, while I is associated with a splinter branch of the “IJ” macrogroup, with the separation from J still unclear.

Having established the Pelasgoi as an Indo-European Bell Beaker culture predating the later Yamnaya waves, we can move on to identifications of the Pelasgoi in ancient sources. As established previously, according to Greek authors, a group of Pelasgoi make their way from Greece to the Po River Valley, potentially the Terramare culture, which collapses and diffuses into proto-Villanovan, and the later Etruscan culture descended from Villanovan. Whether or not the Terramare culture had a significant Pelasgoi element requires further evidence, but it’s clear the Greek authors were accurately telling the story of the diffusion of Terramare into Etruscan.

Herodutus in Book 5 of his histories finds it notable enough to mention a group of “Pelasgoi” on the island of Lemnos.10 Whether or not they got their information from Herodotus, many other Greek authors associated Pelasgians with Lemnos, as well as Crete, and reaffirmed the story of the Po Valley Pelasgians founding the Estruscan city of Spina. Together with the Pelasgoi of Lemnos, Thucydides mentions a group of pirates called “Tyrsenoi”. These Tyrsenoi are variously called “Tyrrenians” and in many references to the Etruscans they are called “Tyrsenoi” by the Greeks, however not all of the Tyrsenoi were Etruscans, with Etruscans representing only one element of the group.11

The earlier identification with the Tyrsenoi and the Pelasgoi of Lemnos may seem strange until looking at a chart of the Etruscan language family, and where other related inscriptions have been found. As we can see, the Lemnian language, part of the Tyrrenian language family, is closely related to the Etruscans, which gives credibility to the classical accounts of Etruscan/Tyrsenian connections to Lemnos.

Also notable on this chart are the Rhaetic speakers of the alps. While academia is still looking for evidence of this theory, there is the likelihood the Rhaetic speakers were essentially Villanovans pushed northward prior to the ethnogenesis of the Etruscan kingdom.

Interestingly, according to Ephorus of Cyme, the Greeks could not colonize Sicily until the 8th century due to these supposed Tyrrenian pirates.12 This would line up with Tyrrenian domination over the seas around italy, but not necessarily imply Tyrrenians were from Sicily, but rather dominated the island, and its surrounding waters.

While readers may presume the name for the Etruscans in their native language is Etruscia, Etruscia was actually the Latin name for the people, being the origin of the modern region Tuscany. How Tyrsenoi connects to E’trusci is unclear, but it’s obvious both the Latins and Greeks shared this term, possibly from common origin. The endonym for the Etruscans was actually “Rassena” with the later “Ra-Ssen-a” being the connection to “Ty-R-Sen-oi”. After burying the lead so long, it should now be clear how “TyRSenoi” morphs into “TyRaS”, sharing all of the major consonants, as well as maintaining the original “Ras'' sound of the “Rassena”.

Deviating for a moment, it is necessary to bring up Roman mythology relating to their origin, as this is the colloquial knowledge regarding Roman origins. The story of Romulus and Remus tells of two twin brothers, born to the Vestal Virgin ‘Rhea Silvia’ daughter to Numitor - King of Alba Longa. Rhea Silvia became pregnant by the god Mars, after being raped, although other sources claim she conceived them in a sacred grove dedicated to Mars after being visited by him. In reality Numitor was the disgraced King of Alba Longa, having been displaced by his brother Amulius, who upon hearing of Rhea Silvia’s pregnancy demands the children be abandoned on the banks of the Tiber, eventually drowning and being washed into the river. Instead, the children are saved by the god of the Tiber, Tiberius, and are suckled by a she-wolf in what is known as the Lupercal cave.

A few key details jump out from this story. First, Rhea Silvia’s “divine conception” so clearly mirrors the conception of Jesus, possibly being the cause of deviation in some stories that view the event as a rape. Another notable detail is how Romulus actually ends up killing Remus, again mirroring many biblical founder stories such as Cain and Abel, or Jacob and Esau. Biblical allusions do not end there, as we see the child being left on the banks of the Tiber, only to be saved, mirrors the story of Moses being saved by Pharaoh’s daughter, only in this case being attributed to divine origin. This story structure was common in the near east, with Sumerian, Akkadian, and Babylonian Kingly founding stories also stemming from children on the banks of a river in a basket miraculously saved.

Not only does her ‘immaculate conception’ mirror Jesus, but also the “second founding event” of Roman mythology, the Rape of the Sabines. In this story, Romulus sets off to find female partners for the growing male dominated city of Rome, having attracted numerous “male bandits”.13 Coincidentally, these “bandits” would fit in with theories of the Pelasgoi and Tyrsenoi being sea bandits, or pirates. Whether or not the original rape of Rhea Silvia happened, it’s clear that Latin, and Roman, history was founded upon raping, pillaging, and general banditry, as per the Pelasgoi. If these stories were meant to play off a religious milieu is difficult to say, but they are clearly steeped in historical context.

While Romans typically used the story of Romulus and Remus to claim godly descent, this story is more about the specific founding of the “City of Rome”, and ignores the wider “Latin” culture that was a subset of the Etruscan Kingdom. Due to the similarity of Terramare and Latin, it’s highly likely Latin descended from Terramare, and may represent the groups of Pelasgians that moved into Etruscan territory. Both of these groups descend from a Proto-Villanovan, pseudo-Urnfield culture - the Urnfield culture being related to the spread of Celts, potentially supporting the Italo-Celtic language family theory.

While later writers, Roman and Christian, would stress this royal connection to classical antiquity, it’s unlikely the wider ‘male’ populace that had become centered on Rome were all “from Rome”, and thus not all from this godly descent. Ultimately, whoever the Etruscans descend from is also the same descent for the Romans, even if there were ethnic differences between Latins and Etruscans. Based on all of the evidence supporting a connection between Pelasgians and Tyrrhenians, Tyrrhenians and Etruscia, Pelasgians and Etruscia/Latium, it is clear that the name of “Tiras” is mean to represent the wider Italic peoples and nations, and possibly even the entire indigenous “Pelasgoi/Tyrsenoi” sphere as the final child of Japheth on the Table.

This week is quite unique in conclusion. Few have ever, in my own estimation, described the nation of Tiras as the indigenous people groups that fuse into Japheth. For many this will be the most contentious idnetification so far, but I feel confident that the information I’ve provided will help convince open minded readers of a new paradigm in viewing the Table of Nations, and elevate a simplistic approach to what is often viewed as a generalized “genealogy”, but is a much deeper political landscape.

We are finally finished with all the children of Japheth. We are not yet finished, as we will discuss identifications of Japheth next week and end with a final chart for all his sons.

I’d be remiss not to remind readers at this point of my book dealing with Japheth, recently published on Amazon. Table of Nations: Japheth

Köbler *Ker (1)

Matthews, W. K. "Baltic origins". p. 51. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

Граков, Борис Николаевич (1971). Скифы. Moscow. pp. 131–132, 160.

A hydronym (from Greek: ὕδρω, hydrō, "water" and ὄνομα, onoma, "name") is a type of toponym that designates a proper name of a body of water. Hydronyms include the proper names of rivers and streams, lakes and ponds, swamps and marshes, seas and oceans.

Tacitus G.45-6

Hampe, Arndt; Rodríguez-Sánchez, Francisco; Dobrowski, Solomon; Hu, Feng Sheng; Gavin, Daniel G. (2013). "Climate refugia: from the Last Glacial Maximum to the twenty-first century". The New Phytologist. 197 (1): 16–18. ISSN 0028-646X

Cardarelli, Andrea (2009). "The Collapse of the Terramare Culture and growth of new economic and social System during the late Bronze Age in Italy". Scienze dell'antichità: Storia Archeologia Antropologia. 15. ISBN 978-88-7140-440-0.

Abulafia (2014), p. 145-6.

Mathisen, Ralph W. (2019). Ancient Roman Civilization. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 60.